CYBERNETIC FUTURES: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

= | <p class="pt-link">[[The Fabulous Loop de Loop#CYBERNETIC_FUTURES|The Fabulous Loop de Loop]]</p> | ||

<p class="parallel-text"> | <p class="parallel-text"> | ||

ANNOTATION:<br> | ANNOTATION:<br> | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

<p class="parallel-text"> | <p class="parallel-text"> | ||

The counterculture movement arose alongside a broader discourse of possible futures: the soviet future of world communism, realised through the unfolding of | The counterculture movement arose alongside a broader discourse of possible futures: the soviet future of world communism, realised through the unfolding of Dialectical Materialism (see Marx for details), set against an emergent liberal orthodoxy, which envisioned a prosperous future founded on increased democracy, shared material prosperity and the mechanisation of labour. Within the United States, this liberal vision of The Affluent Society (John Kenneth Galbraith) opposed the knee-jerk anti-communist movement led by Senator John McCarthy.<br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Seminal works in building a consensus for | Seminal works in building a consensus for ‘Welfare Fordism', in addition to Galbraith’s, ''The Affluent Society'', was Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.’s.,''The Vital Centre'' in which the future adviser to President Kennedy proclaimed: “‘The new radicalism ..[…] has returned ... to the historic philosophy of liberalism – to a belief in the integrity of the individual, in the limited state, in due process of law, in empiricism, in gradualism.’ <ref>Barbrook ''Imaginary Futures'' </ref><br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Daniel Bell’s Commission for the Year 2000 (1964-1968) perhaps most perfectly performs the institutionalisation of the ideology of what Richard Barbrook calls America’s ‘imaginary future’. <ref>Barbrook Imaginary Futures </ref> | Daniel Bell’s Commission for the Year 2000 (1964-1968) perhaps most perfectly performs the institutionalisation of the ideology of what Richard Barbrook calls America’s ‘imaginary future’. <ref>Barbrook ''Imaginary Futures'' </ref> The commission comprised 42 members from elite universities and adopted the interdisciplinary model of the Macy Conferences on Cybernetics, including “not only economists, sociologists and political scientists, but also geographers, biologists and even a professor of Biblical Studies”.<ref>Barbrook ''Imaginary Futures' p.116</ref> The Commission took a positive inflection of the cybernetic ideas of Marshell McLuhan and Norbert Wiener and narrated a future society in dynamic equilibrium. Daniel Bell, in The End of Ideology wrote: “In the Western world […] there is today a rough consensus among intellectuals on political issues: the acceptance of a Welfare State; the desirability of decentralised power; a system of mixed economy and of political pluralism.” <ref>Richard Barbrook, ''Imaginary Futures'' 103</ref><br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

The transition to this future would be made possible through the perfection of computing, media and telecommunications technologies which would allow the democratic process greater immediacy, transparency and responsiveness. As veteran of the Macy conferences on cybernetics, J.C.R. Licklider (ARPA) and Paul Baran (RAND) worked together to build time share mainframes and the software that could allow for communication on what would be ‘the Net’, the commission advocated, and prophesied, the convergence of computing and television technologies; it also predicted, in 1967, that by the year 2000 the majority of US citizens would have access to on-line databases and libraries (a prediction made two years before UCLA and Stanford made the first network connection). The Bell commission painted a picture of the future in which the public would be informed by ‘electronic newspapers’; they would exercise their rights through ‘instant referendums’. Social change would not require political revolution – McLuhan had, after all, assured us that Marx had “missed the communications bus”. Change would come through democratic processes in line with technological evolution as the West, led by the United States as it moved toward the 'the post-ideological society’. Bell, in Towards the Year 2000, wrote: “‘... the world of the year 2000 has already arrived, for the decisions which we make now, in the way we shape our environment and thus sketch the lines of constraints, the future is committed. ... The future is not an overarching leap into the distance; it begins in the present.’ <ref>Daniel Bell, Towards the Year 2000, in Barbrook, Imaginary Futures 117</ref><br> | The transition to this future would be made possible through the perfection of computing, media and telecommunications technologies which would allow the democratic process greater immediacy, transparency and responsiveness. As veteran of the Macy conferences on cybernetics, J.C.R. Licklider (ARPA) and Paul Baran (RAND) worked together to build time share mainframes and the software that could allow for communication on what would be ‘the Net’, the commission advocated, and prophesied, the convergence of computing and television technologies; it also predicted, in 1967, that by the year 2000 the majority of US citizens would have access to on-line databases and libraries (a prediction made two years before UCLA and Stanford made the first network connection). The Bell commission painted a picture of the future in which the public would be informed by ‘electronic newspapers’; they would exercise their rights through ‘instant referendums’. Social change would not require political revolution – McLuhan had, after all, assured us that Marx had “missed the communications bus”. Change would come through democratic processes in line with technological evolution as the West, led by the United States as it moved toward the 'the post-ideological society’. Bell, in Towards the Year 2000, wrote: “‘... the world of the year 2000 has already arrived, for the decisions which we make now, in the way we shape our environment and thus sketch the lines of constraints, the future is committed. ... The future is not an overarching leap into the distance; it begins in the present.’ <ref>Daniel Bell, ''Towards the Year 2000'', in Barbrook, Imaginary Futures 117</ref><br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

These imaginary futures, along with the interdiciplinarity research cultures in which they were incubated, can be understood as products of the discourse of the Cold War. Whilst the Commission for the Year 2000 dreamed of computers which facilitated a more equitable social sphere, IBM, the principle manufacturer of mainframe computers at the time, was actually facilitating a very effective war machine. The System /360, the dominant mainframe in the early 1960s, was adopted by non-military businesses but a larger proportion of IBMs sales went too Military related projects. The first order for a System/360 came from a manufacturer of fighter planes which served in Vietnam; the US Airforce’s nuclear weapons system was powered by 704 mainframe computers supplied by IBM. <ref>Barbrook Imaginary Futures</ref><br> | These imaginary futures, along with the interdiciplinarity research cultures in which they were incubated, can be understood as products of the discourse of the Cold War. Whilst the Commission for the Year 2000 dreamed of computers which facilitated a more equitable social sphere, IBM, the principle manufacturer of mainframe computers at the time, was actually facilitating a very effective war machine. The System /360, the dominant mainframe in the early 1960s, was adopted by non-military businesses but a larger proportion of IBMs sales went too Military related projects. The first order for a System/360 came from a manufacturer of fighter planes which served in Vietnam; the US Airforce’s nuclear weapons system was powered by 704 mainframe computers supplied by IBM. <ref>Barbrook 'Imaginary Futures'</ref><br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

None of this was made apparent at the Worlds Fair of 1964, at which IBM, with the aid of an impressive multi-media installation designed | None of this was made apparent at the Worlds Fair of 1964, at which IBM, with the aid of an impressive multi-media installation designed by Charles and Ray Eames, emphasised a future in which computers would facilitate a leisurely, democratic, and peaceful future. <ref>Charles and Ray Eymes IBM at The Fair 1964</ref><br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

''Alternative ecologies''<br> | ''Alternative ecologies''<br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

The ecological model proposed by Bateson in the 1950s and 1960s (see THE PORTAPAK) can be seen in the context in which alternative futures were posited by economists, sociologist and political theorists, all of whom shared a consensus that free enterprise operating within the structure of liberal, democratic institutions would yield the most equitable society. The political reason which held that capitalism could be managed and liberal values and institutions preserved within society , variously described as 'welfare Fordism', 'the great settlement' or the 'post-industrial society'. The political theorist, | The ecological model proposed by Bateson in the 1950s and 1960s (see THE PORTAPAK) can be seen in the context in which alternative futures were posited by economists, sociologist and political theorists, all of whom shared a consensus that free enterprise operating within the structure of liberal, democratic institutions would yield the most equitable society. The political reason which held that capitalism could be managed and liberal values and institutions preserved within society , variously described as 'welfare Fordism', 'the great settlement' or the 'post-industrial society'. The political theorist, Daniel Bell, went so far as to term this liberal state of homeostasis 'the post ideological society'. <ref>Daniel Bell, in Barnbrook</ref><br> | ||

In the liberal narratives of the future, increased and continuous prosperity would be assisted by significant technological progress. The Commission for the Year 2000 can be seen as an extension of a logic which, in the second half of the twentieth century, is preserved within the apparatus of cybernetics: a technology of control, balance and equilibrium. A system which | In the liberal narratives of the future, increased and continuous prosperity would be assisted by significant technological progress. The Commission for the Year 2000 can be seen as an extension of a logic which, in the second half of the twentieth century, is preserved within the apparatus of cybernetics: a technology of control, balance, and equilibrium. A system which, whilst prone to disruption and disequilibrium, in the manner of Ashby’s homeostat, is able to correct itself.<br> | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

[[Category:Parallel Text]] | [[Category:Parallel Text]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:01, 12 July 2021

ANNOTATION:

|…| Richard Barbrook. Imaginary Futures. 2015

Context: During the 1950s and 60s Gregory Bateson employed cybernetic principles to model social and biological organisation. In the late 1960s Bateson became a key figure in the burgeoning ecological movement which had grown from the “counterculture”.

The counterculture movement arose alongside a broader discourse of possible futures: the soviet future of world communism, realised through the unfolding of Dialectical Materialism (see Marx for details), set against an emergent liberal orthodoxy, which envisioned a prosperous future founded on increased democracy, shared material prosperity and the mechanisation of labour. Within the United States, this liberal vision of The Affluent Society (John Kenneth Galbraith) opposed the knee-jerk anti-communist movement led by Senator John McCarthy.

Seminal works in building a consensus for ‘Welfare Fordism', in addition to Galbraith’s, The Affluent Society, was Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.’s.,The Vital Centre in which the future adviser to President Kennedy proclaimed: “‘The new radicalism ..[…] has returned ... to the historic philosophy of liberalism – to a belief in the integrity of the individual, in the limited state, in due process of law, in empiricism, in gradualism.’ [1]

Daniel Bell’s Commission for the Year 2000 (1964-1968) perhaps most perfectly performs the institutionalisation of the ideology of what Richard Barbrook calls America’s ‘imaginary future’. [2] The commission comprised 42 members from elite universities and adopted the interdisciplinary model of the Macy Conferences on Cybernetics, including “not only economists, sociologists and political scientists, but also geographers, biologists and even a professor of Biblical Studies”.[3] The Commission took a positive inflection of the cybernetic ideas of Marshell McLuhan and Norbert Wiener and narrated a future society in dynamic equilibrium. Daniel Bell, in The End of Ideology wrote: “In the Western world […] there is today a rough consensus among intellectuals on political issues: the acceptance of a Welfare State; the desirability of decentralised power; a system of mixed economy and of political pluralism.” [4]

The transition to this future would be made possible through the perfection of computing, media and telecommunications technologies which would allow the democratic process greater immediacy, transparency and responsiveness. As veteran of the Macy conferences on cybernetics, J.C.R. Licklider (ARPA) and Paul Baran (RAND) worked together to build time share mainframes and the software that could allow for communication on what would be ‘the Net’, the commission advocated, and prophesied, the convergence of computing and television technologies; it also predicted, in 1967, that by the year 2000 the majority of US citizens would have access to on-line databases and libraries (a prediction made two years before UCLA and Stanford made the first network connection). The Bell commission painted a picture of the future in which the public would be informed by ‘electronic newspapers’; they would exercise their rights through ‘instant referendums’. Social change would not require political revolution – McLuhan had, after all, assured us that Marx had “missed the communications bus”. Change would come through democratic processes in line with technological evolution as the West, led by the United States as it moved toward the 'the post-ideological society’. Bell, in Towards the Year 2000, wrote: “‘... the world of the year 2000 has already arrived, for the decisions which we make now, in the way we shape our environment and thus sketch the lines of constraints, the future is committed. ... The future is not an overarching leap into the distance; it begins in the present.’ [5]

These imaginary futures, along with the interdiciplinarity research cultures in which they were incubated, can be understood as products of the discourse of the Cold War. Whilst the Commission for the Year 2000 dreamed of computers which facilitated a more equitable social sphere, IBM, the principle manufacturer of mainframe computers at the time, was actually facilitating a very effective war machine. The System /360, the dominant mainframe in the early 1960s, was adopted by non-military businesses but a larger proportion of IBMs sales went too Military related projects. The first order for a System/360 came from a manufacturer of fighter planes which served in Vietnam; the US Airforce’s nuclear weapons system was powered by 704 mainframe computers supplied by IBM. [6]

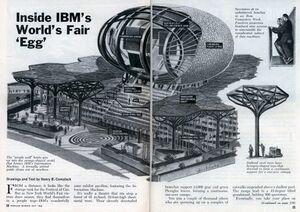

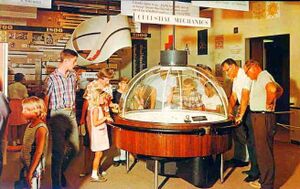

None of this was made apparent at the Worlds Fair of 1964, at which IBM, with the aid of an impressive multi-media installation designed by Charles and Ray Eames, emphasised a future in which computers would facilitate a leisurely, democratic, and peaceful future. [7]

Alternative ecologies

The ecological model proposed by Bateson in the 1950s and 1960s (see THE PORTAPAK) can be seen in the context in which alternative futures were posited by economists, sociologist and political theorists, all of whom shared a consensus that free enterprise operating within the structure of liberal, democratic institutions would yield the most equitable society. The political reason which held that capitalism could be managed and liberal values and institutions preserved within society , variously described as 'welfare Fordism', 'the great settlement' or the 'post-industrial society'. The political theorist, Daniel Bell, went so far as to term this liberal state of homeostasis 'the post ideological society'. [8]

In the liberal narratives of the future, increased and continuous prosperity would be assisted by significant technological progress. The Commission for the Year 2000 can be seen as an extension of a logic which, in the second half of the twentieth century, is preserved within the apparatus of cybernetics: a technology of control, balance, and equilibrium. A system which, whilst prone to disruption and disequilibrium, in the manner of Ashby’s homeostat, is able to correct itself.

- ↑ Barbrook Imaginary Futures

- ↑ Barbrook Imaginary Futures

- ↑ Barbrook Imaginary Futures' p.116

- ↑ Richard Barbrook, Imaginary Futures 103

- ↑ Daniel Bell, Towards the Year 2000, in Barbrook, Imaginary Futures 117

- ↑ Barbrook 'Imaginary Futures'

- ↑ Charles and Ray Eymes IBM at The Fair 1964

- ↑ Daniel Bell, in Barnbrook