Double Bind to Video Therapy

“ A Moebius strip is a one-sided surface made by taking a long rectangle of paper, giving it a half-twist, and joining its ends. Any two points on the strip can be connected by starting at one point and tracing a line to the other without crossing over a inside. The inside is the outside. Here the power of video is used to take in your own outside. When you see yourself on tape, you see the image you are presenting to the world. When you see yourself watching yourself on tape, you are seeing your real self, your 'inside.'”

Paul Ryan – Everyman's Moebius Strip[1]

To briefly recap: In a previous chapter we learned that Alfred Korzybski argued that the etiology of schizophrenia was due to a confusion of levels of abstraction. Korzybski, and the system of General Semantics, maintained that the schizophrenic confused the concrete and the abstract (the map for the territory). Korzybski identified this with Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell’s theory of logical types.[2]

Korzybski built a plastic diagram, the Structural Differential, as a therapeutic aid for those who suffer from category confusion. The Structural Differential was Korzybski’s attempt to establish a new technical standard in the treatment of a condition caused by confusion of logical types. In the same chapter, we established that Bateson also identified schizophrenia as the confusion of levels of abstraction, and that he too referenced Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell’s theory of logical types.

In 1952, Gregory Bateson established a research project at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Palo Alto, entitled The Role of Paradoxes of Abstraction in Communication. Bateson’s team of researchers included anthropologist John Weakland, communications analyst Jay Haley, and psychiatrist William Fry.[3] This research pursued Bateson’s interest in the degree to which the interaction between individuals within groups was formative of the self, and investigated the role that the confusion of levels of abstraction and paradox played in psychological disorders. Just as the structural differential served as an iterative device which established the relation between the concrete event and its symbolic representation, the video system will become central to therapeutic practice as we move toward the 1960s.

Three significant issues arose from the work of Bateson’s Palo Alto group which have a bearing on the development of the video culture of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

- the development of family therapy (which seeks to identify cyclical patterns of family interaction through group work)[4]

- the development of double-bind theory (which has its origins in the conflict of levels of abstraction)

- the use of film and video in the execution and analysis of family therapy sessions.

At this stage I must state the obvious: schizophrenia is not a recursive condition, it is not best described as a “communication problem”, it is not “derived” from the confusion of levels of abstraction and, contrary to the findings of Bateson and his research group, it does not originate with paradoxical patterns of behaviour instigated by the mother.

In 1956 Bateson and the team published the influential paper, Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia, which, nevertheless, framed schizophrenia in precisely those terms.[5] In this paper Bateson described the “double-bind” as “a situation in which no matter what a person does, he ‘can't win.’” In a typical example, a child is presented with a paradox: the family member closest to them tells them they love them but their actions contradict this claim. This sets off a pattern in which the child attempts to resolve the paradox with still more paradoxical forms of communication.[6]

“[I]f the schizophrenia of our hypothesis is essentially a result of family interaction, it should be possible to arrive a priori at a formal description of these sequences of experience which would induce such a symptomatology.”[7]

In Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia, Bateson et al are clear that the confusion of levels of abstraction is essential to any human communication. There are innumerable instances in which it is used in everyday life: “play, non-play, fantasy, sacrament, metaphor” […] “humour”, “simulation of friendliness”, “learning” and learning to learn,[8] alongside non-verbal modes of communication (smiles, shrugs, hugs, nods, winks) which are also highly abstract. The non-schizophrenic is able to navigate this network of signs through interpreting the context in which they are spoken or enacted. The schizophrenic, however (according to Bateson et al), “[…] exhibits weakness in three areas of such function:

(a) He [sic] has difficulty in assigning the correct communicational mode to the messages he receives from other persons.

(b) He has difficulty in assigning the correct communicational mode to those messages which he himself utters or emits nonverbally.

(c) He has difficulty in assigning the correct communicational mode to his own thoughts, sensations, and percepts.” [9]

For the schizophrenic of the double-bind, the channels that link the metaphor to the object it describes are confused. The authors give the example of this syllogism to illustrate the point:

“Men die.

Grass dies.

Men are grass.”

In a certain context this syllogism might illustrate how dependent humans are on negotiating different levels of abstraction to make sense of the world, and how central metaphor is to human communication but:

“[t]he peculiarity of the schizophrenic is not that he uses metaphors, but that he uses unlabeled metaphors. He has special difficulty in handling signals of that class whose members assign Logical Types to other signals.” [10].

In this scheme the schizophrenic has difficulty dealing with the inherent ambiguity of language. Bateson et al give a vivid illustration of how the double-bind might be negotiated by a non-schizophrenic and account for why a schizophrenic is unable to deal with it. They recount the story of the Zen master who, holding a stick in front of his student, instructs the student:

“If you say this stick is real, I will strike you with it. If you say this stick is not real, I will strike you with it. If you don't say anything, I will strike you with it.”[11]

Here the Zen master is inviting the student to read the context, and to act in a manner appropriate to that context (snatch the stick away, accept the blows of the master, call the master’s bluff, &c). The schizophrenic of the double-bind is unable to make such a response.

Here the parallel with Korzybski’s structural differential becomes clearer still. If the etiology of schizophrenia is within the family context then methods which makes the patterns of behaviour apparent to the family members would be highly beneficial. If the family member could witness the miscommunication, they might more readily understand their own place in a matrix of communication. This is a cybernetic vision of therapy, in which all parties are invited to establish a new relation. Just as the structural differential is used as a corrective to errors of interpretation, the video system can be used as a corrective to patterns of behaviour which generate confusion of levels of abstraction.[12] This represents a dramatic break with the “talking cure” of traditional psychiatry, the implications of this form of therapy do not stop with the patient. For the process to be meaningful, the therapist must also acknowledge their part in the ecology of behaviour in which they are immersed.

The shift from one-to-one therapy to family therapy in the 1950s corresponded with the development of technologies in which interaction could be observed and reflected upon. Milton Berger (a follower of Bateson), had incorporated video as a component in his own psychoanalytic practice since 1965. Berger edited an early textbook on video as therapy[13]– and wrote a piece in Radical Software outlining how the techniques provided “[a] unique opportunity for working through alienation from self by repeated replay of recorded data.”[14] The logic of feedback as an agent of self-realisation had been established as an artifice of the apparatus at the inception of video (indeed it might be understood as an outcome of any feedback medium). Video therapist Harry Wilmer speculated, in the pages of Radical Software: “[...] playback becomes FEEDBACK. The patient begins to see himself as he really is. Perhaps, replay means recovery.”[15]

THE REOCCURRENCE OF LAWRENCE KUBIE – A MIRROR WITH A MEMORY

This apprehension of the self as other – this video-activated mirror stage – was recognised by many in the psychoanalytic profession who, with the advent of the video recorder, saw the opportunity for the patient to see themselves as others see them and for the psychoanalyst to see themselves too.[16]

The cybernetician and psychoanalyst, Lawrence Kubie (see also Cybernetics - Dynamic Psychology) explored the psychoanalytical implications of video in his 1969 paper, Some Aspects of the Significance to Psychoanalysis of the Exposure of a Patient to the Televised Audiovisual Reproduction of His Activities. In this text, Kubie gives an account of a self-interview he conducted over a video system. He then plays the footage back, making detailed notes of his experience as he does so. Although the account is given in the third person, the biographical details match those of Kubie. For Kubie, the process uncovered “layers of identification” which intensified with each re-watching.[17]

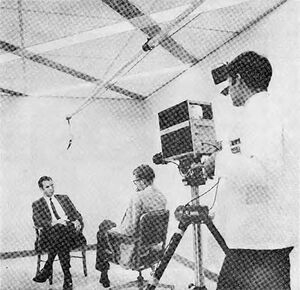

Although video had been used in the medical context for some time – first in surgery in the late 1940s, and then as a training tool for psychiatrists in the 1950s – it wasn’t until early 1960s that the patient became a participant in the media circuit and was allowed access to the tapes. This process, devised by Norman Kagan, David Krathwohl, and Ralph Miller at Michigan State University, was christened Interpersonal Process Recall (IPR).

IPR involved the therapist and the client taping a session before viewing the tape separately and discussing the tapes in subsequent sessions. Krathwohl et al claimed the process of self-reflection on the body language and behaviour by the client “accelerated psychotherapy” and the new situation, in which the tape was the subject of conversation, allowed the client to more readily discuss their feelings and interpret their own actions[18]

Dr. Harry Wilmer, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) was the first to set up a psychiatric television studio in 1967.[19] In the same year he founded the Youth Drug Ward (also known as the “hippy drug ward”), at the Langley Porter Neuropsychiatric Institute (a short distance from the centre of hippy culture, Haight-Ashbury). This facility became a hippy cultural centre in its own right, screening movies and hosting “creativity seminars” (with guests including musician Joan Baez and photographer Ansel Adams.)

Wilmer would later describe the Youth Drug Ward as ‘‘a mix between a far-out school, a free-floating multi-media center, and an electronic therapeutic community.’’[20] Its facilities included closed-circuit television , videotape recorders, 16 mm and 8 mm cameras, audiotape recorders, alongside access to UCSF’s television studio.[21]

Harry Wilmer had first experimented with group therapy in the late 1950s at the United Stated Naval Hospital in Oakland, California, at a time when such practices were considered pioneering. In 1958 (whilst working on double-bind research) Gregory Bateson visited Wilmer’s group therapy sessions at Oakland. Bateson considered Wilmer’s unit to be a ‘‘very extraordinary therapeutic community.’’[22] During Bateson’s week-long visit, the ward was visited by a documentary crew who filmed the group therapy process. Bateson and Wilmer were struck by the degree to which the presence of the camera affected the behaviour of the group. Bateson had previously discussed how the presence of the camera affected a social group being filmed with Margaret Mead – when Bateson had assumed the roles of photographer and camera operator during their trips to Bali and Indonesia. In these anthropological studies the media had folded into the practice, as the subjects of the study viewed themselves as subjects of an anthropological study. The most effective methods with which to film their subjects, whether “artistic” decisions should be kept to a minimum, had been a bone of contention amongst the two anthropologists.[23]

By the early 1960s Wilmer was recommending the use of video within the therapeutic context, in a form which was not simply diagnostic (whereby doctors viewed patients and interpreted their actions) but which also involved the participation of the patients themselves. Wilmer understood this activity in cybernetic terms: ‘‘The essential effect of the immediate playback, is to introduce negative or positive feedback into the social system of psychotherapeutic encounters.’’ [24] As Wilmer developed this practice, he went to great lengths to regulate the flow of information through the system, trying to avoid overload (which results in narcissism or desensitisation). This amounted to a series of procedures, technological rituals, which established best practice and explored new techniques, with a performative, trial and error process. Through this individual approach, it was claimed, the subject is able to find their “true” or “objective” image.

Wilmer gave an account of his use of video as a therapeutic tool in an article for Radical Software entitled, Feed- back: TV Monologue Psychotherapy.

“Television helps mixed-up kids get in focus - on and off camera.”, the byline reads,[25] and the article goes on to proclaim

“The philosophy of the television treatment program is to give a patient self-awareness, yet leave him free - to become involved, silently or actively, or to remain apart from the group. The evils of drugs should not be preached, and adjustment to the world should not be forced. The object is to let the patient see himself through his own eyes, his psychoanalyst's eyes, and the eyes of television.”[26]

Here Wilmer presents an organic, mediative, vision; an ecology in which each actor has their own role in a co-evolutionary process.[27] Video dialogue makes a break with the traditional dialogic relationship between the therapist and the patient (a break that Bateson had advocated in Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry in 1951). The video camera takes the role of the psychoanalyst, serving as a “mirror with memory”, a theatre in which new experimental selves are performed, in which the tape serves to distance the client from their actions. Wilmer gives an account of the various ways in which participants of his programme worked with “TV Monologue PsychoTherapy”:

“Some patients talked excessively to avoid self-revelation. Others relied on objects to establish relationships (i.e., books and musical instruments.) Some read prepared autobiographies, and some read from books. One withdrawn schizophrenic patient read poetic essays from a book. When he saw that his time was running out, he proceeded to finish the book by turning page after page, reading only one line from each page. The total effect was Joyce-like, almost an epic poem. One patient talked about his homosexuality; another about her love for her therapist. A young woman knitted throughout her monologue as she expressed (inner speech) her feelings about a friend's pregnancy and her own feelings about wanting a baby. Another girl sang a song she had written. One patient who was high on acid showed us what a trip was like.”[28]

Wilmer argues that the knowledge of the self gained from TV Monologue Psychotherapy is of a different order to the self awareness which seeks valorisation from others. This higher order of self reflexivity, Wilmer calls “self-awakedness”.

“Confronting one's own image on the television screen, actor-audience experience, produces what I call "self-awakedness" - sudden turning-on of the self. Self-awakedness differs from ordinary social awareness in which the individual may turn to others for verification. Through self-awakedness, these young people who have withdrawn completely from society (often bent on oblivion, seeking rebirth and mystical existence - even death or madness) may find internal strengthening to help them endure the suffering in their lives and to renounce escape through self-destructive behavior and drugs.”[29]

The social model the Youth Drug Ward embodied went beyond the treatment of patients, and beyond particular techniques or technologies of therapy. As a “far-out school” and “free-floating multi-media center” it became a model for alternative society in microcosm, a society where media could aid self-awakedness. It proposed modes of behaviour which went beyond the walls of the clinic. Here an understanding of video as a technology which helped shape the individual could be extended beyond the psychological issue of identity to address an ontological issue of being.

The recognition of video as a therapeutic system that could be used by anyone was outlined in Radical Software by Paul Ryan.[30] In Self Processing, Ryan (echoing Wilmer) warns against over exposure to ones own image, which might cause narcissism or media saturation (which makes one a desensitised “servomechanism”), and outlines a series of procedures for video therapy “so that you might get a taste of processing yourself through tape, so that you might begin to play and replay with yourself.”[31] Ryan draws on Bateson’s cybernetic vision of the “self” as immanent within an informational network, quoting from Bateson's Toward a Theory of Alcoholism: the Cybernetics of 'Self' .

SIMULACRUM – CYBERNETICS – BAUDRILLARD

Bateson:

“[Cybernetics ...]recognizes that the “self” as ordinarily understood is only a small part of a much larger trial- and-error system which does the thinking, acting and deciding. This system includes all the informational pathways which are relevant at any given moment to any given decision. The “self” is a false reification of an improperly delimited part of this much larger field of interlocking processes...” [32]

Ryan draws a picture of the self within the loop of the video circuitry as a moebius strip which has no outside or inside, which, to maintain cohesion, must comprehend its own instability.

“The moebius video strip is a tactic for avoiding both servomechanistic closure and desensitizing in using videotape. Tape can be a tender way of getting in touch with oneself. In privacy, with full control over the process, one can learn to accept the extension out there on tape as part of self. There is the possibility of taking the extending back in and reprocessing over and again on one's personal time warp.”[33]

In Self Processing Ryan gives an account of a three-year old girl who, seeing her own image played back, singing and dancing, felt “compelled to imitate what she saw herself doing on the screen”. [34]

The child is trapped in a loop of repetition, compelled to repeat the actions she sees herself performing. For Ryan this was an example of someone turning themselves into a “servo mechanism” as the little girl used “real time mirror ground rules to deal with her videotape experience.” In contrast to this Ryan advocates using various techniques with the portapak through which one can “learn to accept the extension out there on tape as part of self. There is the possibility of taking the extending back in and reprocessing over and again on one's personal time warp.” [35]

To individualise one must take control of one’s own information, one must process it. The striking thing from our vantage point - at this stage in the loop de loop – is how these actions resemble therapeutic procedures or rituals (Ryan’s video work Everyman’s Mobius Strip was, after all, a video confessional). It is also striking that Ryan describes the girl behaving like a “servomechanism” as she struggles with the mirror with memory. You may remember Lacan translated Freud’s “Wiederholungszwang”, as “automatisme de répétition” – which in English renders “automation of repetition”[36] - when speaking of the actions of the cybernetic tortoise. He also spoke of the tortoise as “jammed” in apprehension of another creature like itself.[37] Just as Lacan sees the trauma of the mirror stage played out in the bodies of two cybernetic tortoises, Ryan sees it played out on a child, who cannot distinguish between the time of the video tape and her own time, and is forced to repeat what is played back to her. And finally, one is struck by how Ryan’s description of the video tape resembles Alfred Korzybski’s structural differential, in its insistence that the subject measures their own place within a hierarchy of abstraction.

Ryan sees the promise of an encounter with the “real” self through video therapy, and the real self is an extended self, a self which is part of a larger system of abstraction. Like the structural differential, it is a technology which helps the subject orientate, as the “self” extends into a larger apparatus (language:media). To “see oneself as one really is” would mean seeing oneself as abstracted on various levels, beyond “a false reification” of self, as the image on the screen, as the body being recorded by the apparatus, as the body participating in the self-prescribed ritual of communication, within what Bateson called “a larger field of interlocking processes”.[38]

If Wilmer's TV Monologue Psychotherapy and Ryan's Self-Processing allow the traditional role of “talking cure” to be outsourced to the video system, it is not the only instance in which a professional category is passed over to the apparatus. From the perspective of the late 60s to early 70s, the role of media professionals will be taken over by media collectives who serve the needs of the local community;“to put the 'consumer' in direct contact with the processes directing the information [they] receive”.[39] On the level of infrastructure, CCTV and CATV will take over the top-down infrastructure of Media America. On a personal and social level, video will become a “mirror with memory” which allows for a greater “self-awakedness” peeling away the “layers of identification”.

- ↑ Paul Ryan, Self Processing, Radical Software, Vol 2, Issue 4, p.9

- ↑ Which held: "The class cannot be a member of itself nor can one of the members be the class, since the term used for the class is of a different level of abstraction—a different Logical Type--from terms used for members."

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015

- ↑ Ray L. Birdwhistell,“Contribution of Linguistic-Kinesic Studies to the Understanding of Schizophrenia,” in Schizophrenia: An Integrated Approach, ed. Alfred Auerback (New York: Ronald Press, 1959), 101.

- ↑ In Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia: “[…]we must expect a pathology to occur in the human organism when certain formal patterns of the breaching [of levels of abstraction] occur in the communication between mother and child”p.1[…] This point is qualified later in the paper: “We do not assume that the double bind is inflicted by the mother alone, but that it may be done either by mother alone or by some combinations of mother, father, and/or siblings.” p3, in Gregory Bateson, Don D. Jackson, Jay Haley, and John Weakland, Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia, Veterans Administration Hospital, Palo Alto, California; and Stanford University, Behavioral Science 1(4): 1956 pp.251-254

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, Don D. Jackson, Jay Haley, and John Weakland, Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia, Veterans Administration Hospital, Palo Alto, California; and Stanford University, 1956 p1

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, Don D. Jackson, Jay Haley, and John Weakland, Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia, Veterans Administration Hospital, Palo Alto, California; and Stanford University, 1956 p.3

- ↑ Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia, p.1

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, Don D. Jackson, Jay Haley, and John Weakland, Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia, Veterans Administration Hospital, Palo Alto, California; and Stanford University, 1956 p.3

- ↑ This notion of the label brings us back to the structural differential. You may remember that Korzybski used labels which denoted different levels of abstraction deriving from the “object event”.

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, Don D. Jackson, Jay Haley, and John Weakland, Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia, Veterans Administration Hospital, Palo Alto, California; and Stanford University, 1956

- ↑ In this way the double-bind necessitates group-family therapy, which calls for systems of mediation which make the double-bind visible to the group (video systems).

- ↑ Videotape Techniques in Psychiatric Training and Treatment, ed. Milton M. Berger (New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1970),

- ↑ Milton Berger, “Multiple Image Self Confrontation,” Radical Software 2, no. 4 (Fall 1973): p.8.

- ↑ Harry A. Wilmer, Feed- back:TV Monologue Psychotherapy, Radical Software p11| note: In Guerrilla TV Michael Shemberg had outlined how, when people apprehend their own image in the fabulous loop de loop, they would understand their own place in the larger media ecology; just as William Burroughs had taught that replaying audio of oneself (or taking an auditing session with an e-meter) can help remove “various misleading data”; just as for Alfred Korzybski’s Structural Differential could help one recognise ones place within a hierarchy of abstraction. The video tape, because of its very structure as a feedback machine, invites a relation to the recursive.

- ↑ Floy Jack Moore, Eugene Chernell, and Maxwell J. West, “Television as a Therapeutic Tool,” Archives of General Psychiatry 12, no. 2 (February 1965): 217–218, 220.

- ↑ Lawrence S. Kubie,“Some Aspects of the Significance to Psychoanalysis of the Exposure of a Patient to the Televised Audiovisual Reproduction of His Activities,” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 148, no. 4 (April 1969)

- ↑ In Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015 p173; Norman Kagan, David R. Krathwohl, and Ralph Miller, “Stimulated Recall in Therapy Using VideoTape: A Case Study,” Journal of Counseling Psychology 10, no. 3 (1963): 237.

- ↑ In Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015 p172

- ↑ cited in Grimaldi p.96:Harry Wilmer, Children of Sham (unpublished manuscript), vol. 2 of the Langley Porter Youth Drug Ward series, box 3, Harry Wilmer Papers, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, 2:3 (hereafter cited as Wilmer, Children of Sham).

- ↑ Carmine Grimaldi, Televising Psyche: Therapy, Play, and the Seduction of Video, Representations 139. Summer 2017, p.96

- ↑ in Grimaldi | Gregory Bateson, ‘‘Analysis of Group Therapy in an Admissions Ward, United States Naval Hospital, Oakland, California,’’ in Harry Wilmer’s Social Psychiatry in Action: A Therapeutic Community (Springfield, IL, 1958),

- ↑ Stewart Brand, For God’s Sake Margaret (1976)`, Co-evolutionary Quarterly

- ↑ Wilmer, ‘‘The Use of Television Videotape in a Therapeutic Community,’’| in

- ↑ Harry A. Wilmer, Feed- back: TV Monologue Psychotherapy, Radical Software p11

- ↑ Harry A. Wilmer, Feed- back:TV Monologue Psychotherapy, Radical Software p11

- ↑ Wilmer:"After the television monologue gives the patient an opportunity to ‘open-up on camera’, playback becomes FEEDBACK. The patient begins to see himself as he really is. Perhaps, replay means recovery.” Harry A. Wilmer, Feed- back:TV Monologue Psychotherapy, Radical Software p11

- ↑ Harry A. Wilmer, Feed- back:TV Monologue Psychotherapy, Radical Software p11

- ↑ Harry A. Wilmer, Feed- back:TV Monologue Psychotherapy, Radical Software p11

- ↑ In 1970 Ryan, had studied Wilmer's work carefully, proposed he project in Ego Me Absolve, in which the subject would seek absolution in a video confessional booth.|cited in Grimaldi, Televising Psyche: Therapy, Play, and the Seduction of Video, Representations 139. Summer 2017

- ↑ Paul From Paul Ryan, Self Processing, Radical Software, p.15: [Everyman’s Moebius Strip] “is designed so that you might get a taste of processing yourself through tape, so that you might begin to play and replay with yourself. Hopefully it will suggest ideas for your own compositions. –Your strip. –Your trip. –Technically, this is the way it works. –Using an audio tape recorder, record the following series of cues, pausing after each instruction for as long as you would want to follow it out. Set yourself up in front of the videocamera for a head and shoulders shot. –Have the monitor off. –Roll the tape. –Follow/don't follow the cues. –Relax and breath deeply, just relax and breath deeply –Loosen up your face by yawning –stretching your neck –working your jaw –Now, explore your face with your fingertips –Touch the favorite part of your faceEx –Close your eyes and think of someone you love –Remember a happy moment with them […]”

- ↑ Bateson Steps Toward an Ecology of Mind

- ↑ Paul Ryan, Self Processing, Radical Software, p.15

- ↑ Paul Ryan, Self Processing, Radical Software, Vol 2, Issue 4, p.9

- ↑ Paul Ryan, Self Processing, Radical Software, Vol 2, Issue 4, p.9

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Dupuy. On the Origins of Cognitive Science : The Mechanization of the Mind ; translated by M. B. DeBevoise. MIT Press, 2009 p 18

- ↑ See Tortoise and Homeostasis'; also Lacan Seminar II

- ↑ Bateson StEM

- ↑ Frank Gillette ERV is Evil, Radical software Issue 1, 1970 p.4