From Schizmogenesis to Feedback: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (121 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="quote-box"> | |||

<p class="quote">Gregory Bateson: "''Communication is the substance of common being.''"</p> | |||

</div> | |||

Gregory Bateson | [[File:Gregory-Bateson-Anthropology-Cultural-Studies-1946_250x250.jpg|thumb|''Gregory Bateson in the 1930s'']] | ||

<p class="preamble">''To briefly recap:'' In the previous chapters I have narrated how the self-organisation expressed by the steam engine invited a comparison with the self-organisation expressed in evolution (this observation was made by Alfred Russel Wallis in 1858). This self-organisation seemed to violate the second law of thermodynamics (entropy), whereby ordered systems run to disorder. The speculative theorists Samuel Butler and the geneticist William Bateson both struggled to articulate what would later be termed negative entropy (the localised consolidation of order within an overall entropic system). For Butler the principle of self-regulation on a biological level had profound implications to our understanding of consciousness and purpose; for William Bateson it allowed an articulation of specific diversity in evolution, whereby information (as opposed to energy) was the agent of adaptation. Samuel Butler and William Bateson mark a shift from a discourse of energy to a discourse of information, to which William Bateson's son, Gregory Bateson will make a profound contribution.</p> | |||

In this chapter I will describe how Gregory Bateson inherited the “problem of entropy” from his father’s generation and how it was carried into his early work as an anthropologist, principally in his study of the Iatmul people in New Guinea, ''Naven'' (1936). The title of the book referred to the name given to a series of honorific rites performed by the Iatmul. Naven presented a society which, despite containing destabilising elements, managed to retain stability in the long term. | |||

As a student at Cambridge in the 1920s he worked in an environment that encouraged a broad, interdisciplinary approach. | As the son of the founder of modern genetics Gregory Bateson grew up in an environment which was open to advanced ideas in relation to systems and as a student at Cambridge in the 1920s he worked in an environment that encouraged a broad, interdisciplinary approach.<ref>Lipset, David. ''Gregory Bateson: The Legacy of a Scientist''. Boston: Beacon Press (MA), 1982</ref> | ||

In | In ''Naven'' (1936), Bateson developed the theory of schismogenesis which was concerned with how groups of people are established through division and how such groups organise and maintain their cohesion. Two general questions emerged from Bateson's observations of the Iatmul: | ||

# how do social systems achieve and maintain balance? | |||

# why don’t they move to runaway and disorder? | |||

In | In Bateson's mature thinking schisomogenesis became synonymous with feedback<ref>Bateson, Gregory, and Bateson, Mary C.. ''Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred''. Hampton Press (NJ), 2004. p.12</ref> and was defined as “change with direction”, <ref>Bateson, Gregory. ''Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind''. New York: Harpercollins, 1996. p.89</ref> but in his earlier theorisation of schisomogenesis Bateson encountered a familiar energy crisis: how could unity in division be maintained, what could account for the generative activity of a society systematically divided within itself?<ref> Bateson had high hopes for the theory of schisomogenesis and worked for some years on a book on the subject. Bateson, Gregory. Naven. Cambridge: CUP Archive, n.d.</ref> | ||

In ''Naven'', Bateson characterised the Iatmul by the marked contrast between the behaviour and ethos of men and women.<ref>Bateson, Gregory. Naven (1936)</ref> This behaviour and ethos are mediated by a series of honorific rituals which involve humiliation and transvestitism. Bateson gives an account of a society regulated by rituals involving extremes of exaggerated boasting and submission. It was through the analysis of this group that Bateson developed the theory of schismogenesis which he believed could be applied across the social sciences. | |||

In ''Naven'' | <p class="floop-link" id="GREGORY_BATESON_–_BIOGRAPHICAL_CHRONOLOGY">[[GREGORY BATESON – BIOGRAPHICAL CHRONOLOGY]]</p> | ||

The elements are: | |||

b) symmetrical | <p class="indent"> | ||

a) Complimentary schismogenesis - characterised by acquiescence, self-deprecation and conciliatory behaviour.<br> | |||

<br> | |||

In the glossary of ''Naven'': “Complementary. A relationship between two individuals (or between two groups) is said to be chiefly complementary if most of the behaviour of the one individual is culturally regarded as of one sort (e.g. assertive) while most of the behaviour of the other, when he replies, is culturally regarded as of a sort complementary to this (e.g. submissive).”<ref>''Naven'' p.308</ref><br> | |||

<br> | |||

b) Symmetrical schismogenesis, characterised by boasting and displays of dominance.<br> | |||

<br> | |||

In the glossary of ''Naven'': “Symmetrical. A relationship between two individuals (or two groups) is said to be symmetrical if each responds to the other with the same kind of behaviour, e.g. if each meets the other with assertiveness.”<ref>''Naven'' p.311</ref> | |||

</p> | |||

Schismogenesis, in the context of the Naven rites, concerned how division is generated within a group, but at this stage, schismogenesis could not articulate a satisfactory account of how cohesion is maintained. In ''Naven'' Bateson stresses how social life is interactive and intersubjective. The actions of one group produce a reaction which may be symmetrical (ritualised boasting, for instance) or complimentary (acquiescence to a hierarchy through submission) in an other. | |||

In | In 1936 Bateson writes “I am inclined to see the status quo as a dynamic equilibrium, in which changes are continually taking place. On the one hand, processes of differentiation tending towards increase of the ethological contrast, and on the other, processes which continually counteract this tendency towards differentiation. The processes of differentiation I have referred to as schismogenesis. I would define schismogenesis as a process of differentiation in the norms of individual behaviour resulting from cumulative interaction between individuals.”<ref>Excerpt From: Bateson, Gregory. “Naven”. Apple Books.</ref> | ||

In ''Sacred Unity'' ( | In ''Sacred Unity'' (1977) Bateson writes: “I could not, in 1936, see any real reason why the [Iatmul] culture had survived so long”.<ref>Bateson, Gregory, and Bateson, Mary C.. ''Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred.'' Hampton Press (NJ), 2004. P.12</ref> The question was, how does one account for self-regulation and adaptation within such a fractious social system, without the ordering, adaptation, self-regulation afforded by negative feedback? The observer could note a division, and, against the odds, the observer could note the system achieving equilibrium – but what could account for the system’s order? Here Bateson redefines Schismogenesis in terms closer to Kenneth Craik and Warren McCulloch, as “a process of interaction whereby directional change occurs in a learning system. If the steps of evolution and/or stochastic learning are random, as has been maintained, why should they sometimes, over long series, occur, recurrently, in the same direction? The answer of course is always in terms of interaction, but in those days we knew approximately nothing about ecology.”<ref>Bateson, Gregory. Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Harpercollins, 1996.</ref> | ||

Schismogenesis, as a theory of social organisation, shifted definition over the years. In ''Naven'' it is defined as a process “of differentiation in the norms of individual behaviour resulting from cumulative interaction between individuals.” | |||

Within a society, for instance, there may be assertive individuals and submissive individuals, corrective elements are necessary to stop the society from running to disorder. Within such a society there are anti- and pro- schismogenetic mechanisms– it is through the play of one force against another that equilibrium is maintained in a dynamic system. | |||

Such a system is opposed to a homeostatic system in which balance is maintained internally. In Bateson’s writings the shift from schismogenesis in a dynamic (entropic) to a homeostatic (negative-entropic) system occurs when Bateson adopts cybernetics as a metatheory, after 1942. | |||

In ''Naven'' (1936) Bateson proposes schismogenesis as a general theory that can be applied to any social grouping. | |||

<p class="body-quote"> | |||

“I think that we should be prepared rather to study schismogenesis from all the points of view —structural, ethological, and sociological— which I have advocated; and in addition to these it is reasonably certain that schismogenesis plays an important part in the moulding of individuals. I am inclined to regard the study of the reactions of individuals to the reactions of other individuals as a useful definition of the whole discipline which is vaguely referred to as Social Psychology. This definition might steer the subject away from mysticism.”<ref>Excerpt From: Bateson, Geogory. ''Naven''. Apple Books.</ref></p> | |||

In 1935, the year before the publication of ''Naven'', Bateson had published ''Culture Contact and Schismogenesis'',<ref>Bateson, Gregory. "Culture Contact and Schismogenesis." Man 35 (1935), p.178</ref> which outlines the theory without specific reference to the Iatmul. As in ''Naven'', Bateson draws a distinction between symmetrical schismogenesis (characterised by assertive behaviour) and complementary schismogenesis (characterised by submissiveness) and discusses various restraining factors: | |||

<p class="body-quote"> | |||

“we need a study of the factors which restrain both types of schismogenesis. At the present moment, the nations of Europe are far advanced in symmetrical schismogenesis and are ready to fly at each other's throats; while within each nation are to be observed growing hostilities between the various social strata, symptoms of complementary schismogenesis. Equally, in the countries ruled by new dictatorships we may observe early stages of complementary schismogenesis, the behavior of his associates pushing the dictator into ever greater pride and assertiveness.”</p> | |||

This is typical of Gregory Bateson the synthesist. A principle is applied to a particular instance and then theorised in general terms which encompass the social on a broader scale. An anthropological analysis of a particular group of people becomes a means through which to read, and correct, political division in the 1930s. This instinct to synthesise is a characteristic of his career and cybernetics will provide the consummate vehicle for a meta-theory which spans previously incommensurate boundaries. After Bateson’s serious engagement with cybernetics the theory of schismogenesis was indeed adapted to accommodate notions of negative entropy and homeostasis. Social division – altered variables within a system – are regulated by homeostasis. <ref>Note: For a contemporary reading of schizmogenesis: In ''The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity'' (2021) David Graeber & David Wengrow suggest that the tendency of social groups to exaggerate their differences allows these groups to clearly define themselves against each other. This allows people to build social systems self-consciously. Simply put: an egalitarian society might define itself against its authoritarian neighbour. David Graeber & David Wengrow; ''The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity'', Penguin (2021), p504</ref> | |||

In | In the epilogue of the 1958 edition of ''Naven'', Bateson gives a reflexive, even self-deprecating, review of the 1936 edition of the book: “The book is clumsy and awkward, in parts almost unreadable", reports Bateson.<ref> Bateson, Gregory. ''Naven'' Epilogue to (second) 1958 edition p.281</ref> Exposure to cybernetic ideas had, in the intervening time, allowed him to synthesise information he had gained from his anthropological research with his 1950s work in the field of psychiatry (Bateson’s work with Jurgen Ruesch and double bind communication will be discussed in detail later). By 1958, Bateson understood ''Naven''(1936) to be a study of ''the nature of explanation''. “[I]t is an attempt at synthesis, a study of the ways in which data can be fitted together, and the fitting together of data is what I mean by ‘explanation.’”<ref> Bateson, Gregory. ''Naven'' Epilogue to (second) 1958 edition p.281</ref> This, from the 1940s on, can be understood as Bateson’s purpose, to bring data from disparate sources together into some form of systematic unity. Bateson recognises a more philosophic purpose: “to learn something about the very nature of explanation, to make clear some part of that most obscure matter—the process of knowing.”<ref> Bateson, Gregory. ''Naven'' Epilogue to 1958 (second) edition p.281</ref> | ||

Reflecting on ''Naven'' in 1958, Bateson describes three levels of abstraction – which sketch out a map of the nature of explanation. The first level involves the arrangement of data about the Iatmul. This gives an account of how the Iatmul live. The second level involves discussion of “procedures by which the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle are put together”.<ref> Bateson, Gregory. ''Naven'' Epilogue to 1958 (second) edition, p.282</ref> This generates a lexicon of specialist terminology particular to the discourse in question. The third level is Bateson’s realisation that the terminology generated to describe the object of research (terms such as ethos, eidos, sociology, economics, cultural structure, social structure) “refer only to scientists' ways of putting the jigsaw puzzle together.” This is not to say that the terminology bears no relation to objective reality, but that it exists at a particular level of abstraction. The terminology (discourse) is itself inevitably part of the system it describes. This self-reflexive epistemology, based, in Bateson's case, on a synthesis of Russell & Whiteheads’ Theory of Types and cybernetics will later be termed “second order cybernetics”. | |||

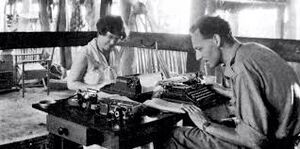

[[File:BatesonMead.jpeg|thumb|''Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, Middle Sepik, Indonesia, 1938''.]] | |||

''' | Still later, in ''Mind and Nature'' (1976) Bateson wrote: | ||

<p class="body-quote"> | |||

“[I]n the 1930s I was already familiar with the idea of ‘runaway’ and was already engaged in classifying such phenomena and even speculating about possible combinations of different sorts of runaway. But at that time, I had no idea that there might be circuits of causation which would contain one or more negative links and might therefore be self-corrective”<ref>Bateson, Gregory. Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity. Hampton Press (NJ), 2002. p.105</ref></p> | |||

Bateson: ''“ | In ''Sacred Unity'', for instance, schismogenesis is re-visited in terms with which the cybernetician Ross Ashby would be familiar. Bateson states: ''“(a) that progressive change in whatever direction must of necessity disrupt the status quo; and (b) that a system may contain homeostatic or feedback loops which will limit or re-direct those otherwise disruptive forces.”''<ref>In their encounter with occidental culture the Iatmul are faced with a dilemma of self-preservation: “either the inner man must be sacrificed or the outer behaviour will court destruction” There is a battle around whose self will be destroyed “that which survives will be a different self”,because a new relation has been introduced adaptation to the disruption is necessary. Bateson, Gregory. ''Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind''. New York: Harpercollins, 1996. P.112/P.113</ref> | ||

In Bateson’s late work, ''Angels Fear'' (with Mary Catherine Bateson 1980), schismogenesis is defined simply as “positive feedback”.<ref>Bateson, Gregory, and Mary C. Bateson. Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred. Hampton Press (NJ), 2004. Glossary</ref> Schismogenesis therefore moved from a theory which suffered the same energy crisis as many nineteenth-century theories (including Freud’s Dynamic Psychology)(in 1936); to a theory which is resolved by homeostatic theories of the cyberneticians (after 1942). Until the emergence of the theory of feedback and homeostasis, Bateson had been in the same epistemological pickle as Freud. | |||

In 1936 Bateson had high ambitions for the theory and in ''Naven'', he offered that it could be applied across the social sciences.<ref>Bateson, Gregory. 1936. Naven: A Survey of the Problems Suggested by a Composite Picture of the Culture of a New Guinea Tribe Drawn from Three Points of View. Cambridge; Cambridge University Press; Second Edition, with a Revised Epilogue, 1958, Stanford: Stanford University Press</ref> For Bateson, schismogenesis offered an improvement of Freudian methods, which, for Bateson, were over-reliant on the subjective narrative offered by the client. Bateson's accounts of the Iatmul in ''Naven'' stress the interdependence of the groups and individuals within that society, in this context the concept of an individuality that transcends the social seems peculiarly occidental. In every aspect of life, in every action and interaction, the Iatmul understand themselves as part of a ''social matrix''. For Bateson, the narrative of subjectivity encouraged in Freudian psychoanalysis obstructed the realization that the patient's condition is co-efficient with interaction with others. In ''Naven'' Bateson establishes the ground for his critique of Freud which he would pursue in ''Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry'' (1951) in which an application of the theory of schismogenesis serves to oppose the diachronic emphasis of Freudian analysis. | |||

<p class="body-quote"> | |||

“In Freudian analysis and in the other systems which have grown out of it, there is an emphasis upon the diachronic view of the individual, and to a very great extent cure depends upon inducing the patient to see his life in these terms. He is made to realise that his present misery is an outcome of events which took place long ago, and, accepting this, he may discard his misery as irrelevantly caused. But it should also be possible to make the patient see his reactions to those around him in synchronic terms, so that he would realise and be able to control the schismogenesis between himself and his friends.”''<ref>Bateson, Gregory. ''Naven'', 1936, p.181</ref></p> | |||

Bateson | Bateson’s disagreement with Freud rested on two pillars, the first was Freud’s dependence on what Bateson called the “diachronic view of the individual” which, in Bateson’s view, did not allow the individual to sufficiently understand the context which shapes them (The social matrix). Bateson considered Freudian methods to be particularly unhelpful to psychotic and schizophrenic individuals.<ref>Bateson, Gregory. ''Naven'', 1936, p.181</ref> Bateson's emphasis, based on his work with the Iatmul, was that individual behaviour was a result of cumulative interaction between individuals. This diachronic emphasis, in which the biography of the individual is prioritised, was local to occidental cultures, and should not be universalised. | ||

The second critique of Freudian analysis rested on the very energy crisis which had plagued Bateson’s theorisation of schismogenesis. In the 1930s Bateson had described schismogenesis as a system of “progressive change in dynamic equilibrium”. Freud had also tried to square the energy circle with the Freudian fallacy of Dynamic Psychology. Bateson’s revision of Freud, and of his revision of his own theory of schismogenesis would rely on a new relation between energy and information proposed by cybernetics. | |||

<div class="chapter-links"> | |||

<div class="previous-chapter">[[A (Proto) Cybernetic Explanation|A (Proto) Cybernetic Explanation ←]]</div> | |||

<div class="next-chapter">[[Negative Entropy – Bateson - Freud|→ Negative Entropy – Bateson - Freud]]</div> | |||

</div> | |||

[[Category:Fabulous_Loop_de_Loop Chapters]] | |||

Latest revision as of 09:13, 23 August 2022

Gregory Bateson: "Communication is the substance of common being."

To briefly recap: In the previous chapters I have narrated how the self-organisation expressed by the steam engine invited a comparison with the self-organisation expressed in evolution (this observation was made by Alfred Russel Wallis in 1858). This self-organisation seemed to violate the second law of thermodynamics (entropy), whereby ordered systems run to disorder. The speculative theorists Samuel Butler and the geneticist William Bateson both struggled to articulate what would later be termed negative entropy (the localised consolidation of order within an overall entropic system). For Butler the principle of self-regulation on a biological level had profound implications to our understanding of consciousness and purpose; for William Bateson it allowed an articulation of specific diversity in evolution, whereby information (as opposed to energy) was the agent of adaptation. Samuel Butler and William Bateson mark a shift from a discourse of energy to a discourse of information, to which William Bateson's son, Gregory Bateson will make a profound contribution.

In this chapter I will describe how Gregory Bateson inherited the “problem of entropy” from his father’s generation and how it was carried into his early work as an anthropologist, principally in his study of the Iatmul people in New Guinea, Naven (1936). The title of the book referred to the name given to a series of honorific rites performed by the Iatmul. Naven presented a society which, despite containing destabilising elements, managed to retain stability in the long term.

As the son of the founder of modern genetics Gregory Bateson grew up in an environment which was open to advanced ideas in relation to systems and as a student at Cambridge in the 1920s he worked in an environment that encouraged a broad, interdisciplinary approach.[1]

In Naven (1936), Bateson developed the theory of schismogenesis which was concerned with how groups of people are established through division and how such groups organise and maintain their cohesion. Two general questions emerged from Bateson's observations of the Iatmul:

- how do social systems achieve and maintain balance?

- why don’t they move to runaway and disorder?

In Bateson's mature thinking schisomogenesis became synonymous with feedback[2] and was defined as “change with direction”, [3] but in his earlier theorisation of schisomogenesis Bateson encountered a familiar energy crisis: how could unity in division be maintained, what could account for the generative activity of a society systematically divided within itself?[4]

In Naven, Bateson characterised the Iatmul by the marked contrast between the behaviour and ethos of men and women.[5] This behaviour and ethos are mediated by a series of honorific rituals which involve humiliation and transvestitism. Bateson gives an account of a society regulated by rituals involving extremes of exaggerated boasting and submission. It was through the analysis of this group that Bateson developed the theory of schismogenesis which he believed could be applied across the social sciences.

GREGORY BATESON – BIOGRAPHICAL CHRONOLOGY

The elements are:

a) Complimentary schismogenesis - characterised by acquiescence, self-deprecation and conciliatory behaviour.

In the glossary of Naven: “Complementary. A relationship between two individuals (or between two groups) is said to be chiefly complementary if most of the behaviour of the one individual is culturally regarded as of one sort (e.g. assertive) while most of the behaviour of the other, when he replies, is culturally regarded as of a sort complementary to this (e.g. submissive).”[6]

b) Symmetrical schismogenesis, characterised by boasting and displays of dominance.

In the glossary of Naven: “Symmetrical. A relationship between two individuals (or two groups) is said to be symmetrical if each responds to the other with the same kind of behaviour, e.g. if each meets the other with assertiveness.”[7]

Schismogenesis, in the context of the Naven rites, concerned how division is generated within a group, but at this stage, schismogenesis could not articulate a satisfactory account of how cohesion is maintained. In Naven Bateson stresses how social life is interactive and intersubjective. The actions of one group produce a reaction which may be symmetrical (ritualised boasting, for instance) or complimentary (acquiescence to a hierarchy through submission) in an other.

In 1936 Bateson writes “I am inclined to see the status quo as a dynamic equilibrium, in which changes are continually taking place. On the one hand, processes of differentiation tending towards increase of the ethological contrast, and on the other, processes which continually counteract this tendency towards differentiation. The processes of differentiation I have referred to as schismogenesis. I would define schismogenesis as a process of differentiation in the norms of individual behaviour resulting from cumulative interaction between individuals.”[8]

In Sacred Unity (1977) Bateson writes: “I could not, in 1936, see any real reason why the [Iatmul] culture had survived so long”.[9] The question was, how does one account for self-regulation and adaptation within such a fractious social system, without the ordering, adaptation, self-regulation afforded by negative feedback? The observer could note a division, and, against the odds, the observer could note the system achieving equilibrium – but what could account for the system’s order? Here Bateson redefines Schismogenesis in terms closer to Kenneth Craik and Warren McCulloch, as “a process of interaction whereby directional change occurs in a learning system. If the steps of evolution and/or stochastic learning are random, as has been maintained, why should they sometimes, over long series, occur, recurrently, in the same direction? The answer of course is always in terms of interaction, but in those days we knew approximately nothing about ecology.”[10] Schismogenesis, as a theory of social organisation, shifted definition over the years. In Naven it is defined as a process “of differentiation in the norms of individual behaviour resulting from cumulative interaction between individuals.” Within a society, for instance, there may be assertive individuals and submissive individuals, corrective elements are necessary to stop the society from running to disorder. Within such a society there are anti- and pro- schismogenetic mechanisms– it is through the play of one force against another that equilibrium is maintained in a dynamic system.

Such a system is opposed to a homeostatic system in which balance is maintained internally. In Bateson’s writings the shift from schismogenesis in a dynamic (entropic) to a homeostatic (negative-entropic) system occurs when Bateson adopts cybernetics as a metatheory, after 1942.

In Naven (1936) Bateson proposes schismogenesis as a general theory that can be applied to any social grouping.

“I think that we should be prepared rather to study schismogenesis from all the points of view —structural, ethological, and sociological— which I have advocated; and in addition to these it is reasonably certain that schismogenesis plays an important part in the moulding of individuals. I am inclined to regard the study of the reactions of individuals to the reactions of other individuals as a useful definition of the whole discipline which is vaguely referred to as Social Psychology. This definition might steer the subject away from mysticism.”[11]

In 1935, the year before the publication of Naven, Bateson had published Culture Contact and Schismogenesis,[12] which outlines the theory without specific reference to the Iatmul. As in Naven, Bateson draws a distinction between symmetrical schismogenesis (characterised by assertive behaviour) and complementary schismogenesis (characterised by submissiveness) and discusses various restraining factors:

“we need a study of the factors which restrain both types of schismogenesis. At the present moment, the nations of Europe are far advanced in symmetrical schismogenesis and are ready to fly at each other's throats; while within each nation are to be observed growing hostilities between the various social strata, symptoms of complementary schismogenesis. Equally, in the countries ruled by new dictatorships we may observe early stages of complementary schismogenesis, the behavior of his associates pushing the dictator into ever greater pride and assertiveness.”

This is typical of Gregory Bateson the synthesist. A principle is applied to a particular instance and then theorised in general terms which encompass the social on a broader scale. An anthropological analysis of a particular group of people becomes a means through which to read, and correct, political division in the 1930s. This instinct to synthesise is a characteristic of his career and cybernetics will provide the consummate vehicle for a meta-theory which spans previously incommensurate boundaries. After Bateson’s serious engagement with cybernetics the theory of schismogenesis was indeed adapted to accommodate notions of negative entropy and homeostasis. Social division – altered variables within a system – are regulated by homeostasis. [13]

In the epilogue of the 1958 edition of Naven, Bateson gives a reflexive, even self-deprecating, review of the 1936 edition of the book: “The book is clumsy and awkward, in parts almost unreadable", reports Bateson.[14] Exposure to cybernetic ideas had, in the intervening time, allowed him to synthesise information he had gained from his anthropological research with his 1950s work in the field of psychiatry (Bateson’s work with Jurgen Ruesch and double bind communication will be discussed in detail later). By 1958, Bateson understood Naven(1936) to be a study of the nature of explanation. “[I]t is an attempt at synthesis, a study of the ways in which data can be fitted together, and the fitting together of data is what I mean by ‘explanation.’”[15] This, from the 1940s on, can be understood as Bateson’s purpose, to bring data from disparate sources together into some form of systematic unity. Bateson recognises a more philosophic purpose: “to learn something about the very nature of explanation, to make clear some part of that most obscure matter—the process of knowing.”[16]

Reflecting on Naven in 1958, Bateson describes three levels of abstraction – which sketch out a map of the nature of explanation. The first level involves the arrangement of data about the Iatmul. This gives an account of how the Iatmul live. The second level involves discussion of “procedures by which the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle are put together”.[17] This generates a lexicon of specialist terminology particular to the discourse in question. The third level is Bateson’s realisation that the terminology generated to describe the object of research (terms such as ethos, eidos, sociology, economics, cultural structure, social structure) “refer only to scientists' ways of putting the jigsaw puzzle together.” This is not to say that the terminology bears no relation to objective reality, but that it exists at a particular level of abstraction. The terminology (discourse) is itself inevitably part of the system it describes. This self-reflexive epistemology, based, in Bateson's case, on a synthesis of Russell & Whiteheads’ Theory of Types and cybernetics will later be termed “second order cybernetics”.

Still later, in Mind and Nature (1976) Bateson wrote:

“[I]n the 1930s I was already familiar with the idea of ‘runaway’ and was already engaged in classifying such phenomena and even speculating about possible combinations of different sorts of runaway. But at that time, I had no idea that there might be circuits of causation which would contain one or more negative links and might therefore be self-corrective”[18]

In Sacred Unity, for instance, schismogenesis is re-visited in terms with which the cybernetician Ross Ashby would be familiar. Bateson states: “(a) that progressive change in whatever direction must of necessity disrupt the status quo; and (b) that a system may contain homeostatic or feedback loops which will limit or re-direct those otherwise disruptive forces.”[19]

In Bateson’s late work, Angels Fear (with Mary Catherine Bateson 1980), schismogenesis is defined simply as “positive feedback”.[20] Schismogenesis therefore moved from a theory which suffered the same energy crisis as many nineteenth-century theories (including Freud’s Dynamic Psychology)(in 1936); to a theory which is resolved by homeostatic theories of the cyberneticians (after 1942). Until the emergence of the theory of feedback and homeostasis, Bateson had been in the same epistemological pickle as Freud.

In 1936 Bateson had high ambitions for the theory and in Naven, he offered that it could be applied across the social sciences.[21] For Bateson, schismogenesis offered an improvement of Freudian methods, which, for Bateson, were over-reliant on the subjective narrative offered by the client. Bateson's accounts of the Iatmul in Naven stress the interdependence of the groups and individuals within that society, in this context the concept of an individuality that transcends the social seems peculiarly occidental. In every aspect of life, in every action and interaction, the Iatmul understand themselves as part of a social matrix. For Bateson, the narrative of subjectivity encouraged in Freudian psychoanalysis obstructed the realization that the patient's condition is co-efficient with interaction with others. In Naven Bateson establishes the ground for his critique of Freud which he would pursue in Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry (1951) in which an application of the theory of schismogenesis serves to oppose the diachronic emphasis of Freudian analysis.

“In Freudian analysis and in the other systems which have grown out of it, there is an emphasis upon the diachronic view of the individual, and to a very great extent cure depends upon inducing the patient to see his life in these terms. He is made to realise that his present misery is an outcome of events which took place long ago, and, accepting this, he may discard his misery as irrelevantly caused. But it should also be possible to make the patient see his reactions to those around him in synchronic terms, so that he would realise and be able to control the schismogenesis between himself and his friends.”[22]

Bateson’s disagreement with Freud rested on two pillars, the first was Freud’s dependence on what Bateson called the “diachronic view of the individual” which, in Bateson’s view, did not allow the individual to sufficiently understand the context which shapes them (The social matrix). Bateson considered Freudian methods to be particularly unhelpful to psychotic and schizophrenic individuals.[23] Bateson's emphasis, based on his work with the Iatmul, was that individual behaviour was a result of cumulative interaction between individuals. This diachronic emphasis, in which the biography of the individual is prioritised, was local to occidental cultures, and should not be universalised.

The second critique of Freudian analysis rested on the very energy crisis which had plagued Bateson’s theorisation of schismogenesis. In the 1930s Bateson had described schismogenesis as a system of “progressive change in dynamic equilibrium”. Freud had also tried to square the energy circle with the Freudian fallacy of Dynamic Psychology. Bateson’s revision of Freud, and of his revision of his own theory of schismogenesis would rely on a new relation between energy and information proposed by cybernetics.

- ↑ Lipset, David. Gregory Bateson: The Legacy of a Scientist. Boston: Beacon Press (MA), 1982

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory, and Bateson, Mary C.. Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred. Hampton Press (NJ), 2004. p.12

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Harpercollins, 1996. p.89

- ↑ Bateson had high hopes for the theory of schisomogenesis and worked for some years on a book on the subject. Bateson, Gregory. Naven. Cambridge: CUP Archive, n.d.

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Naven (1936)

- ↑ Naven p.308

- ↑ Naven p.311

- ↑ Excerpt From: Bateson, Gregory. “Naven”. Apple Books.

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory, and Bateson, Mary C.. Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred. Hampton Press (NJ), 2004. P.12

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Harpercollins, 1996.

- ↑ Excerpt From: Bateson, Geogory. Naven. Apple Books.

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. "Culture Contact and Schismogenesis." Man 35 (1935), p.178

- ↑ Note: For a contemporary reading of schizmogenesis: In The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (2021) David Graeber & David Wengrow suggest that the tendency of social groups to exaggerate their differences allows these groups to clearly define themselves against each other. This allows people to build social systems self-consciously. Simply put: an egalitarian society might define itself against its authoritarian neighbour. David Graeber & David Wengrow; The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, Penguin (2021), p504

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Naven Epilogue to (second) 1958 edition p.281

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Naven Epilogue to (second) 1958 edition p.281

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Naven Epilogue to 1958 (second) edition p.281

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Naven Epilogue to 1958 (second) edition, p.282

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity. Hampton Press (NJ), 2002. p.105

- ↑ In their encounter with occidental culture the Iatmul are faced with a dilemma of self-preservation: “either the inner man must be sacrificed or the outer behaviour will court destruction” There is a battle around whose self will be destroyed “that which survives will be a different self”,because a new relation has been introduced adaptation to the disruption is necessary. Bateson, Gregory. Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Harpercollins, 1996. P.112/P.113

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory, and Mary C. Bateson. Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred. Hampton Press (NJ), 2004. Glossary

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. 1936. Naven: A Survey of the Problems Suggested by a Composite Picture of the Culture of a New Guinea Tribe Drawn from Three Points of View. Cambridge; Cambridge University Press; Second Edition, with a Revised Epilogue, 1958, Stanford: Stanford University Press

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Naven, 1936, p.181

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Naven, 1936, p.181