The Tortoise and Homeostasis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

Psychology at the University of Rome on September 26 and 27, 1953</ref> In this paper, also known as The Rome Discourse, Lacan set out to upgrade Freudian psychoanalysis to meet the technical standards of the mid-twentieth century. For Lacan this meant psychoanalysis had to “take back its own property” –to go back to the first principles of Freud in which the analysis of language was central. For Lacan, recent developments in structural linguistics (Roman Jakobson) and structural anthropology (Claude Levi-Strauss) provide “methods” through which Freudian psychoanalysis could be theorised anew. These methodological tools allowed Lacan to recognise a structural equivalence between the different elements of his neo-Freudian psychoanalysis.<ref>Note:In the Rome Discourse Lacan describes the relation as follows. On structural linguistics: “…the reference to linguistics will introduce us to the method which, by distinguishing synchronic from diachronic structurings in language, will enable us to better understand the different value our language takes on in the interpretation of resistances and of transference, and to differentiate the effects characteristic of repression and the structure of the individual myth in obsessive neurosis.”. Structural anthropology affords similar advantages:” “[I]t seems to me that these [psychoanalytical] terms can onlv be made clearer if we establish their equivalence to the current language of anthropology, or even to the latest problems in philosophy, fields where psychoanalysis often need but take back its own property.” </ref> | Psychology at the University of Rome on September 26 and 27, 1953</ref> In this paper, also known as The Rome Discourse, Lacan set out to upgrade Freudian psychoanalysis to meet the technical standards of the mid-twentieth century. For Lacan this meant psychoanalysis had to “take back its own property” –to go back to the first principles of Freud in which the analysis of language was central. For Lacan, recent developments in structural linguistics (Roman Jakobson) and structural anthropology (Claude Levi-Strauss) provide “methods” through which Freudian psychoanalysis could be theorised anew. These methodological tools allowed Lacan to recognise a structural equivalence between the different elements of his neo-Freudian psychoanalysis.<ref>Note:In the Rome Discourse Lacan describes the relation as follows. On structural linguistics: “…the reference to linguistics will introduce us to the method which, by distinguishing synchronic from diachronic structurings in language, will enable us to better understand the different value our language takes on in the interpretation of resistances and of transference, and to differentiate the effects characteristic of repression and the structure of the individual myth in obsessive neurosis.”. Structural anthropology affords similar advantages:” “[I]t seems to me that these [psychoanalytical] terms can onlv be made clearer if we establish their equivalence to the current language of anthropology, or even to the latest problems in philosophy, fields where psychoanalysis often need but take back its own property.” </ref> | ||

The other key structural element in Lacan’s discourse of 1953-1955 is his reading of the German idealist Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. In the 1930s, Lacan had taken part in Alexandre Kojève’s seminars on Hegel’s ''Phenomenology of the Spirit''. These highly influential seminars had been attended by a generation of thinkers who would shape the intellectual life in France over the coming decades, including Bataille, Deleuze, Foucault and Derrida.<ref> Richard L. Warms & R. Jon McGee. ''Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology. An Encyclopedia'' Sage, 2013; Mark Poster, The Hegel Renaissance: Toward a Philosophical Anthropology, in ''Existential Marxism in Postwar France From Sartre to Althusser'', Princeton University Press (1975)</ref> | The other key structural element in Lacan’s discourse of 1953-1955 is his reading of the German idealist Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. In the 1930s, Lacan had taken part in Alexandre Kojève’s seminars on Hegel’s ''Phenomenology of the Spirit''. These highly influential seminars had been attended by a generation of thinkers who would shape the intellectual life in France over the coming decades, including Bataille, Deleuze, Foucault and Derrida.<ref> Richard L. Warms & R. Jon McGee. ''Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology. An Encyclopedia'' Sage, 2013; Mark Poster, The Hegel Renaissance: Toward a Philosophical Anthropology, in ''Existential Marxism in Postwar France From Sartre to Althusser'', Princeton University Press (1975)</ref> In Kojève’s reading, Hegel held that the self and the social are mutually constitutive. This is exemplified in Hegel’s master-slave dialectic in which the subject is constituted – brought into a whole – in relation to the Other.<ref> Alexandre Kojève (1902-1968), ''Introduction to the Reading of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit,'' Assembled by Raymond Queneau, Basic Books (1969).</ref> This reading of Hegel had been transposed into Lacan’s psychoanalytical theory by the mid 1930s, as is evident in Lacan’s formulation of the mirror stage (1936), in which unity of the self is established in its apprehension of the self as Other. For Lacan, the moment when the infant apprehends the self in the Other, it enters the realm of the symbolic – it enters language. | ||

To understand Kojève’s reading of Hegel goes a long way in explaining Lacan’s mode of address circa 1953-1955. Lacan, like Kojive, recognises the dialectic of history, that thought is relative to time. This dialectical time begins with the recognition of I in the Other, which is the moment when the subject enters language. | |||

To understand Kojève’s reading of Hegel goes a long way in explaining Lacan’s mode of address circa 1953-1955. Lacan, like Kojive, recognises the dialectic of history, that thought is relative to time. This dialectical time begins with the recognition of I in the | |||

Kojève states, in the introduction to his own seminar: | Kojève states, in the introduction to his own seminar: | ||

Revision as of 15:45, 9 August 2020

Jacques Lacan: “The organism, already convinced as a machine by Freud, has a tendency to return to its state of equilibrium – this is what the pleasure principle states”

Cybernetics Arrives in Paris

The reception of cybernetics and information theory in Paris in the early 1050s was mixed. Some were suspicious of a discourse which appeared to be an agent of a technocratic instrumental reason. Some, including Henri Lefebvre and Jean Paul Sartre[1] understood the imposition of cybernetics and information theory was another example of the creeping cultural hegemony of the United States. [2] On the other hand, for many European intellectuals, cybernetics presented the opportunity to make a clean break with the trappings of the past: humanist liberalism, idealist individualism and Cartesian dualism. Some had been seriously engaged with American cybernetic and information theory in America itself during WWII. Roman Jakobson and Claude Levi-Strauss, for instance, had studied at Ecole Libre des Hautes Etudes in New York during the Nazi occupation of France. Ecole Libre was a francophone academy in exile, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, which strongly supported the emerging scientific disciplines of cybernetics and information theory. Jakobson and Levi-Strauss both incorporated elements of information theory, game theory and cybernetics into the disciplines of structural linguistics and structural anthropology.[3]

Jacques Lacan attempted a similar synthesis by situating the discourse of cybernetics and information theory within the frame of Hegelian dialectics and Freudian psychoanalysis. Lacan manages this by positioning cybernetics as part of the shift from the discourse of knowledge (which dominated since the enlightenment) to the discourse of the machine (which would dominate the coming age of communication and control).[4]

Lacan will argue that Freud’s theories, despite being born into the discourse of knowledge, could readily be adapted to the discourse of the machine (indeed Lacan credits Freud with actually anticipating many of the changes to come). Lacan acknowledges that the nineteenth-century entropic model of “psychic energy” requires revision. This is to replaced by the cybernetic notion of homeostasis which more accurately demonstrates the distribution of information (as opposed to energy) within a system.

There is a central question dominating Lacan’s work from The Rome Discourse (1953) and through to his seminar from 1953-1955 which we will examine in the coming chapters.

Th question is (crudely put):

How can psychoanalysis meet the technical standards of the mid-twentieth century?

The answer to that question (crudely put) is:

One must recognise the shift from the discourse of knowledge (which dominated the enlightenment and after) to the discourse of the machine (which will dominate the age of communication and control).

Lacan does not condone or condemn cybernetics, but he does acknowledge the need to adapt to discourse of the machine. For Lacan, cybernetics represented a tendency which had developed over two centuries. Lacan traces the genesis of this shift toward the discourse of the machine to the 1700s when mathematical systems of probability were first introduced. [5] Such systems proposed a subject exterior to the symbolic order they were part of. The 1700s witnessed another development which would shape future discourse. Calculating machines were invented which were capable of organising complex numbers in sequence (Pascal’s Pascaline and Leibniz’s calculator, for example). Thereafter knowledge is inscribed within the machine, which again places the subject in exterior relation to the symbolic systems which inscribes them as subjects.

Lacan: Hegel, Structuralism and Cybernetics: from The Rome Discourse to Seminar books I and II (1953-1955).

In the year before Seminar II[6] Jacques Lacan had delivered the paper “The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis” at the Rome Congress held at the Institute of Psychology at the University of Rome. (1953).[7] In this paper, also known as The Rome Discourse, Lacan set out to upgrade Freudian psychoanalysis to meet the technical standards of the mid-twentieth century. For Lacan this meant psychoanalysis had to “take back its own property” –to go back to the first principles of Freud in which the analysis of language was central. For Lacan, recent developments in structural linguistics (Roman Jakobson) and structural anthropology (Claude Levi-Strauss) provide “methods” through which Freudian psychoanalysis could be theorised anew. These methodological tools allowed Lacan to recognise a structural equivalence between the different elements of his neo-Freudian psychoanalysis.[8]

The other key structural element in Lacan’s discourse of 1953-1955 is his reading of the German idealist Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. In the 1930s, Lacan had taken part in Alexandre Kojève’s seminars on Hegel’s Phenomenology of the Spirit. These highly influential seminars had been attended by a generation of thinkers who would shape the intellectual life in France over the coming decades, including Bataille, Deleuze, Foucault and Derrida.[9] In Kojève’s reading, Hegel held that the self and the social are mutually constitutive. This is exemplified in Hegel’s master-slave dialectic in which the subject is constituted – brought into a whole – in relation to the Other.[10] This reading of Hegel had been transposed into Lacan’s psychoanalytical theory by the mid 1930s, as is evident in Lacan’s formulation of the mirror stage (1936), in which unity of the self is established in its apprehension of the self as Other. For Lacan, the moment when the infant apprehends the self in the Other, it enters the realm of the symbolic – it enters language.

To understand Kojève’s reading of Hegel goes a long way in explaining Lacan’s mode of address circa 1953-1955. Lacan, like Kojive, recognises the dialectic of history, that thought is relative to time. This dialectical time begins with the recognition of I in the Other, which is the moment when the subject enters language.

Kojève states, in the introduction to his own seminar:

Kojève: “Man is Self-Consciousness. He is conscious of himself, conscious of his human reality and dignity; and it is in this that he is essentially different from animals, which do not go beyond the level of simple Sentiment of self. Man becomes conscious of himself at the moment when-for the ‘first’ time-he says ‘I.’ To understand man by understanding his ‘origin’ is, therefore, to understand the origin of the I revealed by speech.”[11]

Kojève goes on to outline that (for Hegel) the subject locates their Self Conciousness through desire. This can be a basic desire such as hunger or sexual desire. This desire can be recognised in the other. This desire brings an encounter with the self which is realised in language – the becoming of the "I". This encounter creates subjectivity and allows the "transformation" of an alien reality into its own realty" and "assimilation" of its other.[12]

And here, in Seminar I, Lacan discusses the coming into self-consciousness, in psychoanalytical terms, with Jean Hyppolite (the principle translator and commentator of Hegel in France):

Lacan “The subject originally locates and recognises desire through the intermediary, not only of his own image, but of the body of his fellow being. It's exactly at that moment that the human being's consciousness, in the form of consciousness of self, distinguishes itself. It is in so far as he recognises his desire in the body of the other that the exchange takes place. It is in so far as his desire has gone over to the other side that he assimilates himself to the body of the other and recognises himself as body.” [13]

This connection to Kojève's Hegel accounts for the overall dialectical nature of Lacan’s argumentation around the time of the Rome Discourse (1953-1955) when Lacan was setting forward his re-formulation of psychoanalysis.

The exchange between Hyppolite and Lacan also carries across Seminar’s I and Seminar II. For instance, in Seminar Book II Hyppolite points out that our relation to the machine has shifted radically in recent history. This allows Lacan to unpack this change of relation in dialectical terms, and to outline consequent change in the human subject position with particular relation to cybernetics.

In Seminar II, the dialectical structure again becomes apparent when Lacan describes a coming into being of consciousness which is conditioned by changes in technology: the advent of Huygen's clock, the emergence of probability, the introduction of the steam engine. Each technological innovation has structured particular types of subjectivity. A parallel dialectic unfolds in Seminar II when Lacan distinguishes three different periods in human development: (1) animistic order (2) exact science and (3) conjectural science. In Lacan’s unfolding dialectic each era establishes new horizons of possibility.

I’ve taken time to outline this Hegelian, dialectical construction because when Lacan discusses cybernetics, and the activities of servo-machines within this unfolding dialectic, the moment when the subject enters into language becomes central, particularly at a moment when machines appear to apprehend themselves in another machine and even exhibit elementary desire.

Seminar II

Central to Lacan’s Seminar II was the issue that had been at the heart of the critique of Freudian energetics conducted by Kubie and McCulloch (see previous chapter). This was the issue of homeostasis and how a re-evaluation of the nineteenth century energy model ushered in by cybernetics necessitated a re-evaluation of Freudian dynamic psychology. For Lacan, our understanding of homeostasis in the age of servo-mechanisms shifts discourse from the discourse of knowledge to the discourse of the machine. [14] We have seen in the previous chapter that this discourse was familiar in and around the Macy Conferences on Cybernetics (1946-1953) […] We have also established that the “vapour engine” had been introduced into the discourse of evolution as early as the 1860s by Samuel Butler. Even in the 1900s the self-correction of such machines could be regarded as synonymous with “thinking”.

In Seminar II, Lacan cites a particular type of servomechanism, which has a particular relation to information and energy. Such a machine has the ability to process information coming from its environment and adjust its subsequent actions accordingly. Such a machine had been gliding in a hesitant gait across the floor of the 1951 Paris congress on cybernetics only a few years before– Grey Walter’s tortoise. We note at this point that Grey Walter actually demonstrated an augmentation of the original tortoise at the 1951 congress. The CORA (Condition Reflex Analogue) attempted to take its interaction with the environment to a further stage of abstraction than the original machine (see chapter seven). In his Seminar II, when discussing the role of homeostasis in the formation of the subject, Lacan will propose an augmentation to a mobile servomechanism, the significance of which we will discuss in this chapter.

But first we must recap what is at stake in Seminar II, which can be read as an extension of the debate on Freudian energetics conducted by Bateson, McCulluch and Kubie a few years before (which we discussed in the previous chapter).

Freud's Dynamic Psychology

Freud, when developing the system of psychotherapy, built on the dynamic physiology of his former teacher Ernst Brücke (1819 – 1892). This held that every living organism is an energy system that abides to the principle of the conservation of energy (the fourth law of thermodynamics). This model holds that the amount of energy within a system remains constant. The energy can be transferred and redirected but it cannot be destroyed. From this Freud derived the idea of dynamic psychology, which allowed that, in the manner of kinetic energy, psychic energy can be reorganised within the system but cannot be destroyed. The mind has the ability to redirect and repress psychic energy, diverting it from conscious thought. Classically, the libido, which is the source of sexual energy, becomes redirected, to be manifest in different forms of behaviour. In Freud’s later works a similar dynamic operates as the ego, id and superego struggle for equilibrium. Psychotherapy becomes a technique which rebalances the equilibrium of psychic energy within the system.2[15]

In Lacan’s reading of the Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud is repeatedly struggling with the invisible issues of negentropy and homeostasis, but Freud lacked the theoretical equipment to make the connection between entropy in the machine and biological realm and its relation to information and communication: “the idea of living evolution, the notion that nature always produces superior forms, more and more elaborated, more and more integrated, better and better built organisms, the belief that progress of some sort is imminent in the movement of life, all this is alien to [Freud] and he explicitly repudiates it.” 3[16] Here evolution, as a homeostatic agent serves as a generative regulator it controls the system within established variables but it also allows growth and adaptation.

In Seminar II’s The Circuit [17], Lacan describes Freud’s pleasure principle as follows:

“when faced with a stimulus encroaching on the living apparatus, the nervous system is, as it were, the indispensable delegate of the homeostat, of the indispensable regulator, thanks to which the living being survives and to which corresponds a tendency to lower excitation to a minimum.”

This “minimum” for a living organism is homeostasis. The literal minimum of excitation would, however, be death. There is an important distinction to be drawn here. For Lacan, when Freud speaks of the “death instinct” he speaks of man stepping out of the “limits of life” which is “experience, human interchanges, intersubjectivity”. The withdrawal from sensory input affords survival and regulation. For Lacan it is precisely this homeostatic ability which is the negentropic “rabbit inside the hat”, a previously unaccounted for surfeit. Lacan makes an explicit relation between energy [E] entropy [H] and message [M]: “Mathematicians qualified to handle these symbols locate information as that which moves in the opposite direction to entropy”4 Lacan goes on to further describe the relation between information and entropy and their generative properties: “[…] if information is introduced into the circuit of the degeneration of energy, it can perform miracles. If Maxwell’s demon can stop the atoms which move too slowly, and keep only those which have a tendency to be a little on the frantic side, he will cause the general level of energy to rise again, and will do, using what would have degraded into heat.” A key thread running through Seminar II is the introduction of negative entropy which fundamentally changed the discourse of entropy (in which indestructible forces are held in dynamic equilibrium) to the discourse of homeostasis, communication and control. The ordering of the subject is bound to the signal-noise ratio even to the extent that the most rudimentary non-conscious cybernetic device (the tortoise), by feeding news of order through its nervous system, can express purposeful behaviour.

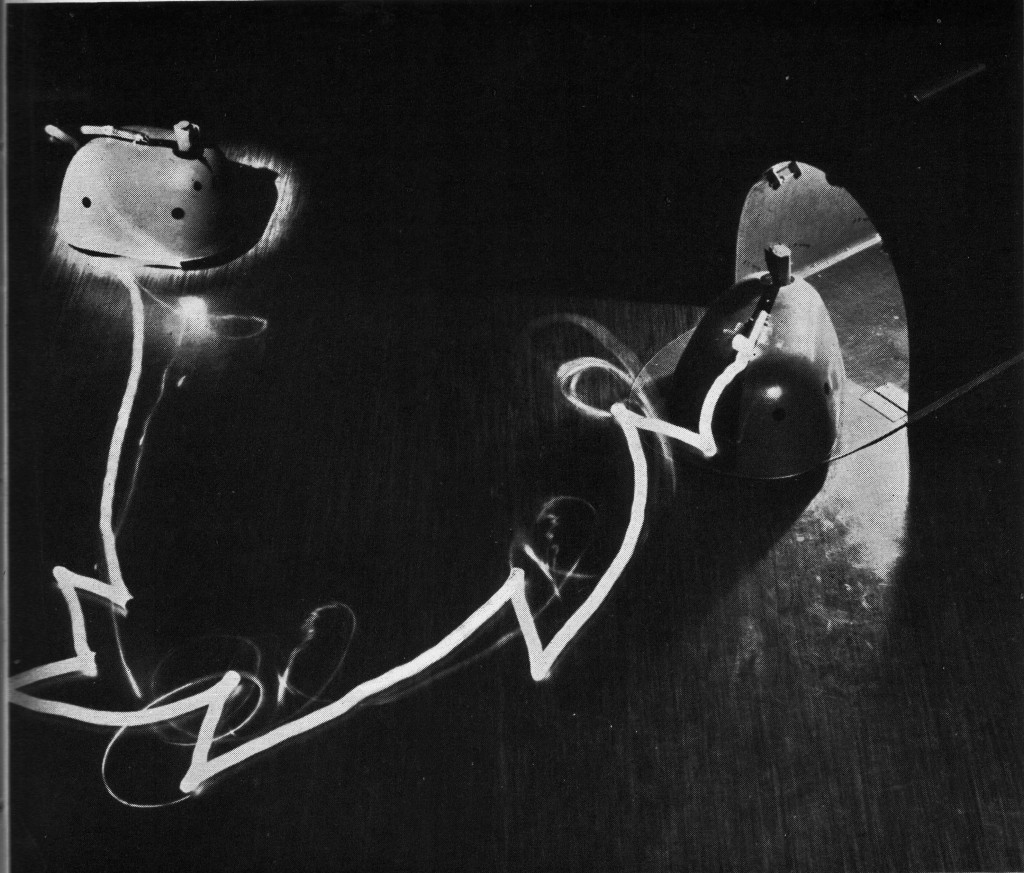

In ‘A Materialist Definition of the Phenomenon of Consciousness’ [18] Lacan recounts the encounter between two cybernetic machines “one of these small turtles or foxes […] which are the playthings of the scientists of our time” [..] “Which we know how to furnish with homeostasis and something like desires”. The machines operate with a light sensitive sensor and, crucially the behaviour of one is determined by that of the other. Indeed the “unity of the first machine depends on that of the other” as long as one gives the “model or form of unity” [...] “whatever it is that the first is orientated toward will be that which the other is orientated towards”. Lacan sees in cybernetics an affirmation of the reality that the organism encounters itself in the other. Here the cybernetic dance provides a reenactment of the mirror stage. This relation also describes something closed to Gregory Bateson’s ecology of mind, in which the subject’s formation is immanent to circuit of negative feedback.

Even such rudimentary devices as the tortoise “learned” to navigate the space they were in and negotiate with other versions of themselves – sometimes colliding and sometimes “jamming” – as one tortoise is frozen in apprehension of the other. Lacan identifies the desire of such a machine is to restock its energy sources (Machina Speculatrix did indeed return to base to recharge itself). In this case the desire of the machine is the source of its nourishment. The desire of the machine to withdraw into its hutch is linked with the desire of the machine to continue. The fact that the machine can protect itself through withdrawal, by creating a stop-gap or buffer from the data-stream of the outside world is central to Lacan’s re-formulation of Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Desire is provided by the source of the initial signal; purpose is established by the feedback of organism-machine and source; the machine must periodically withdraw, to step out of limits of life which is experience, interchanges and intersubjectivity.

In the case of Machina Speculatrix the circuit is rudimentary, it is purely reflexive, a memory without storage. Lacan next suggests adaptations to the design of the mobile servo-machine: if the machine is fitted with recording equipment, a “legislator” intervenes with commands which “regulate the ballet”, this introduces a higher degree of symbolic regulation. 8[19] This represents a voice which is external to the machine which is nevertheless mixed with the circuitry of the apparatus. When Lacan discusses augmenting the tortoises with additional sensors he is not speaking purely speculatively, he is describing a machine such as Grey Walter’s CORA Mrk. 1.

In The Living Brain Grey Walter describes the seven stage circuitry required for a mechanism to acquire a conditioned response. Here, acquired knowledge feeds into the circuitry in long and short feedback loops. The circuit diagram of CORA provides a map of homeostasis. (see fig.) The correct functioning of CORA Mrk 1 would require the machine to store information about a previous action and to act in response to it. This is a stage of abstraction removed from the first generation of tortoises (Elsie and Elma). In Seminar II, Lacan recognised that the basic roaming cybernetic device (such as the tortoise) required some augmentation in order to go to the next stage, which would require a rudimentary “memory”. In the cybernetic device these take the form of symbolic units of difference – these feed through the circuitry of the machine as a cluster of 1/0 – on/off – light/dark – the world encoded as a memory which translates as a learned response. This is still some light years from human consciousness but from this point the distance becomes a matter of degree. 1) the performative response (the tortoise) 2) the performative response augmented (CORA Mrk. 1) These follow the actions of neurons and the action of computation in a computer such as SEER.

For Lacan such machines provide models for the formation of the subject and also provide the basis for intersubjectivity. One machine is “jammed” in its encounter with the other, as it encounters itself in the other. Here servomechanisms and humans share similarities which they do not share with animals, they are both able to regulate their environment. The animal is “Jammed” in a particular sense, it is in a genetic jam because it cannot reflect on its own condition and adapt its environment. Humans have a unique relation to their environment because they can change it and themselves. In the post cybernetic era, humans and machines share a material relation to the world through manipulation of the symbolic system. The moment when it apprehends itself in the other is the moment when the nascent subject grasps unity. If the body in pieces finds its unity in the image of the other, as Lacan writes, it is within the circuitry of cybernetic creatures that the model of homeostatic co-dependency is expressed.

At this point in Seminar II – once Lacan had outlined the role of the servomechanism in positioning the subject– Hyppolite interjects, offering two observations:

1) that the meaning of the machine has changed since the advent of cybernetics, and

2) that it is the human passion for mathematics that makes humans “partners to the machine”.

These two observations allow Lacan to address two of the central themes of his assessment of cybernetics in relation to the shift from the discourse of knowledge to that of the machine.

These are, principally

(1) the shift from the entropy model of energy to the homeostatic (negentropic) model of energy and

(2) the development of the science of probability in the sixteenth century,[20] which provided the conditions for humans to become partners to the machine.

Later in the seminar, in his lecture on Cybernetics and the Unconscious, Lacan will identify this as the era of “conjectural science”. Throughout the seminar Lacan describes the shifting horizon of possibility that takes place as the implications of these two things take hold on human life.

In his approach to Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Lacan seeks to update our reading of Freud in the light of current (post cybernetic) knowledge of homeostasis. Freud encountered the same energy question as other nineteenth century thinkers: in an entropic universe how could one account for order in the first instance? It was possible to approach the crisis by understanding systems in dynamic equilibrium, but without an adequate theory of homeostasis.11 the theorist of system was in danger of falling into the metaphysics of vitalism and energetics – which must rely on a vague notions such as a “life force” to plug the energy gap.[21]

Earlier in his career Freud had practiced in the context which relied on the model of the reflex-arc, which attempted to understand the organism’s relation to environment through input stimulus. In this scheme stimulus provides excitation to action. This theory proposed a hierarchy of reflexes “higher reflexes, reflexes of reflexes...” &c.13 Freud opposed this “reflex architecture” and, anticipating neuron theory, counter-proposed the concept of the “buffer” (this has some relation to Claude Bernard’s milieu interieur). 14

In relation to neuron theory, later experiments, including those of McCulloch and Pitts, would confirm the functioning of synapsis as “contact barriers” and the equilibrating system of filters which “damps down” the synaptic charge (negative feedback). In cybernetic terms, there are checks in the system which avoid “overrun” or positive feedback. The cybernetic tortoises express this in very rudimentary terms. In Lacan’s reading, Freud’s “genius” was that he anticipated a conception of the psyche as working in equilibrium and even described the function, but Freud lacked the theory which accounted for the energy deficit, which Lacan characterises as “pulling the rabbit out of the hat”. Freud did not succeed in finding a coherent model of consciousness principally because he lacked the theoretical apparatus provided by a theory of homeostasis and the cybernetic conception of negentropy.15[22]

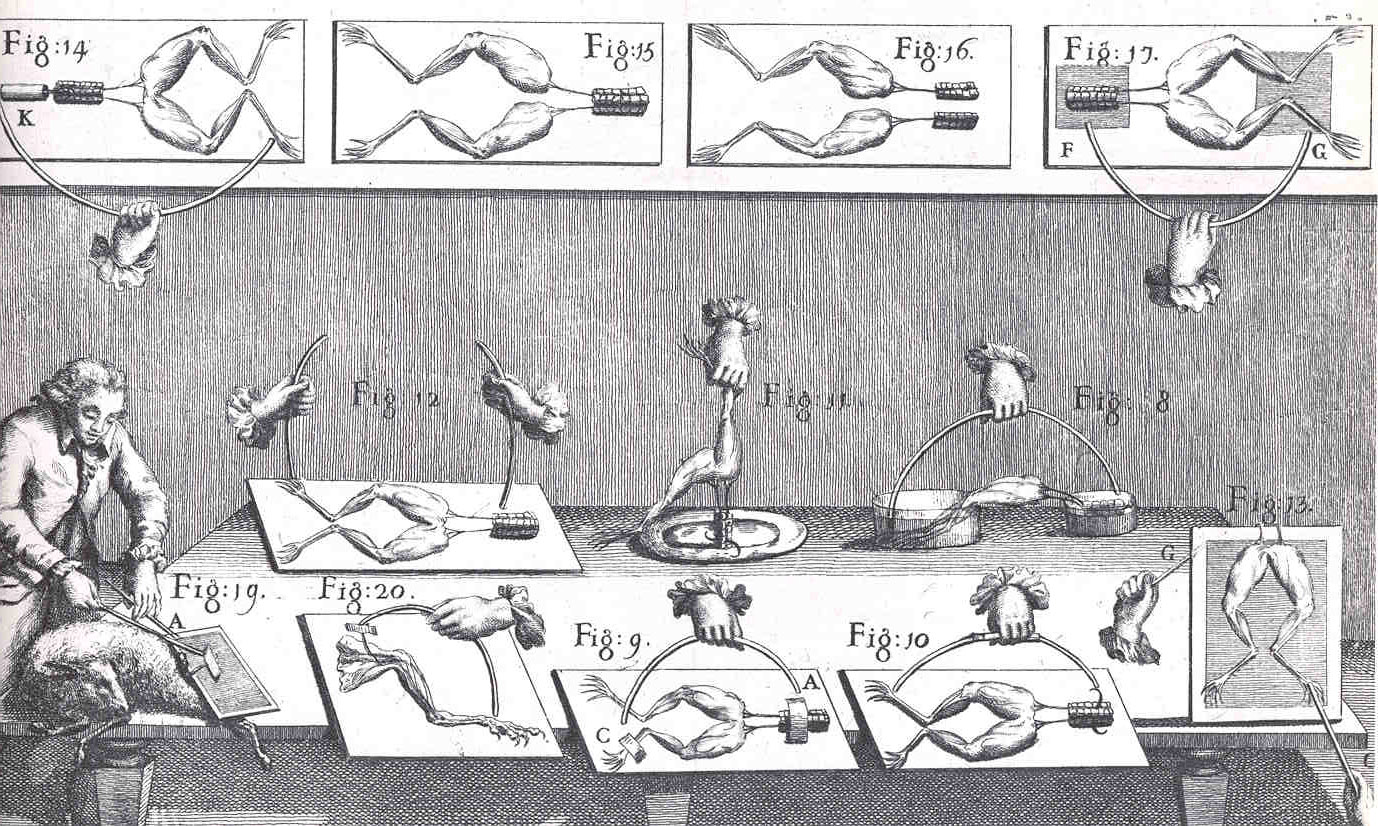

A renewed understanding of entropy invites not only a reassessment of Freudian discourse but of discourse in general. Lacan goes into detailed description of how the discourse of knowledge transitioned into the discourse of the machine.17: [23] In tracing the development of this discourse Lacan gives the example of Galvini’s experiment with an electric charge to the leg of a dead frog (1791),16 which gave rise to the notions of “animal electricity” and “vitalism”. Here the energy problem remains. In order to “pull a rabbit out of a hat”, Lacan remarks, one must first place the rabbit into the hat. Lacan mentions that an earlier attempt to account for this energy surfeit, Condillac (1716-1780), was conditioned by the lack of a sufficient model to describe entropy. “[Condillac] didn’t have a formula for it, because he came before the steam engine. The era of the steam engine, its industrial exploitation, and administrative projects and balance-sheets, were needed, for us to ask the question – what does a machine yield?”18 Lacan identifies the “metaphysics” in such an approach, whether one seeks recourse in “energetics” or “vitalism”. “For Condillac, as for others, more comes out than was put in. They were metaphysicians.”19[24]

Before the advent of cybernetics, there is no adequate account of how that rabbit got into the hat. In Lacan’s unfolding dialectic, Wiener’s theory of negentropy and Claude Shannon’s information theory are the only things that can legitimately account for the rabbit’s miraculous appearance.20 Lacan recognises that the horizon of possibilities shifts as the administration of the system of knowledge changes, and that the change is dependent on a particular technological development – be it the steam engine, or the servo-mechanism. This is not to say that the machine produces the discourse, Lacan is careful to give accounts in which each is produced by the other in a discursive feedback loop. The language within Lacan’s account, in which “balance sheets” speak of the fantasy of economic equilibrium and “yield” speaks of economic and energetic surplus, emphasises the very energy crisis in which the discourse is situated. The machines described by Lacan encode, inscribe and send symbolic material into the world – they produce discourse.

Lacan next elaborates the discourse of energy in the light of Hegel’s dialectic and sets this against the emerging discourse of cybernetics. Lacan understands the second to be a dialectical outworking of the first. We have established that if Hegel is concerned with the discourse of knowledge, cybernetics is concerned with the discourse of the machine. Hegel, in the first instance, allows us to see man as co-extensive to discourse, knowledge is “more than a tete e tete with God”, Lacan suggests. In the discourse of cybernetics man is co-extensive with the machine. In Lacan’s account we see the discourse of the machine prefigured in the time of Pascal (with the Pascaline calculating machine) and Huygen (with the clock) whereby man first understood himself as being constituted by symbolic systems – and machines which measure and regulate those systems – which are outside of the self.

Galvini's experiment with a frog's leg

Before Galvini’s experiment with the frog’s leg the notion that humans were “energised” was not part of discourse. Lacan notes that Hegel had little or nothing to say about energy – there was no steam engine in the Hegelian universe to provide a model for human energy; the crisis of equilibrium that would accompany the invention of the steam engine and the establishment of the second law of thermodynamics was yet to occur. It is at the point when machines exhibit behaviour that another conception of self is possible, and it is in the cybernetic era that information and energy find their equivalence.

In Lacan’s discourse a change in human conception of what constitutes a human is influenced at every turn by a machine which causes a change in conception of what is possible: The calculating machine (Pasciline) presages an era 21 in which the human subject is answerable to systems of probability which are exterior to self; the clock presages a human subject who is beholden to an exterior symbolic order; the steam engine introduces the economy of energy and entropy into the problematic of what constitutes man; servomechanisms, such as Grey Walter’s tortoise, introduce the notion of negentropy, resolving the nineteenth century energy crisis but at the same time making the organism equivalent to the machine. Hegel's discourse was a a discourse on knowledge, but if a machine can think, what does a machine know, and how does a machine know?

The issue of energy becomes central at the point when the steam engine is common (in the time of Freud). Freud intuited that the pleasure principle corresponded to a state of equilibrium, where dynamic forces produce a balance, but he did not have a scientific model or the embodiment of homeostasis in a machine. The model would be provided by Cannon in the 1930s and the machine would be provided by the British neurophysiologists and cybernetician Grey Walter.

new

Lacan and Maxwell's Demon

I began by pointing out that Lacan's Seminar Books I and II are framed in the context of the Rome Discourse of 1953 .”[25], which sought to bring psychoanalysis in line with the technical standards of the mid 1950s. It was Lacan’s aim to return to Freud’s emphasis on the analysis of language as the central activity of psychoanalysis.

I also pointed out that the broad frame for this new programme was provided by Alexandre Kojève’s analysis of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. This was itself a combination of Hegel, Heidegger and Marx. Kojève had imported the notions from Heidegger into his own reading of Hegel. Lacan's world of exact science is one in which there is a limit to what can be known. The world of exact science can be understood as ontic (in the Heideggerian sense). The ontic refers to knowledge which is given: simple or complicated matters of fact which are independent of human mind and human action. Once the ontic is established there is nothing new to know about it. The world of exact science, in which everything is in its proper place – the planets spin in their allotted configuration and the properties of the physical world are stable – is such a world. Ontological questions are of a different order, because they cannot easily be assigned a place and do not have limits or boundaries (the question of Being, is one such question).

The era of conjectural science disrupts the ontic stability of the world of exact science because the stable relation between humans and knowledge is challenged. It is in the context of conjectural science that humans achieve a more radical level of exteriority. In the era of conjectural science, it becomes evident that we are produced by symbolic systems that function despite our own existence (non-human agents of subjectivity that are produced by a symbolic order exterior to the subject). It is at this stage that we begin to understand our intersubjectivity in relation to those systems. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit might be understood, dialectically, as a coming to terms with this modern, administrative world of checks and balances, of probabilities, ratios and averages. His work is a response to the production of subjectivity in the aftermath of the era of conjectural science.

In Seminar II Lacan rightly points out that Hegel has nothing to say about energy. The invention of the steam engine introduces a new era in which the human relation to knowledge is again disrupted. In the era of steam a crisis of subjectivity is produced and a new synthesis of knowledge is required. As the dialectic unfolds, humans suddenly become aware that their fate is tied inexorably to entropy. The ontological crisis of self in the 1800s, becomes an energy crisis. An explanation for this is provided by Freud, who formulates the theory of dynamic psychology. And this goes some way to establishing a relation between the subject and the discourse of energy which produces that subject.

In the cybernetic era, Bateson, McCulloch and Kubie (among others) are quick to see the deficiencies Freud’s energetic model. The ‘vapour engine’, which had initiated the crisis, actually holds the solution, because it does something more than distribute energy in order to produce an equilibrium. It also produces information about itself and its environment which it feeds through its system in order to adapt and change (negative entropy). The governor, in Hegelian terms, embodies the thesis, antithesis and synthesis of the cybernetic era. It is at the point where the vapour engine’s younger cousin, the cybernetic tortoise, scuttles uneasily across the floor, where Lacan engages with the new, non-human, performative, agents of subjectivity. The discourse is no longer about knowledge, or about energy but about the subject’s relation to negentropic systems which are radically exterior to it, and yet which constitute it. The new discourse of information and communication.

In the Rome Discourse Lacan had outlined the stake of language in the new information age. Lacan points out that recent innovations in communication found it necessary to reduce redundancy in speech and to emphasise information (the signal-noise ratio), but for Lacan:“[T]he function of language in speech is not to inform but to evoke. What I seek in speech is a response from the other.”[26] Lacan returns to the master slave dialectic in order to articulate this new crisis of communication. “What constitutes me as a subject is my question. In order to be recognized by the other, I proffer what was only in view of what will be. In order to find him, I call him by a name that he must assume or refuse in order to answer me.” [27]

“If I now face someone to question him, there is no cybernetic device imaginable that can turn his response into a reaction. The definition of "response" as the second term in the "stimulus-response" circuit is simply a metaphor sustained by the subjectivity attributed to animals, only to be elided thereafter in the physical schema to which the metaphor reduces it. This is what I have called putting a rabbit into a hat so as to pull it out again later. But a reaction is not a response.”

Lacan will return to the metaphor of the Rabbit again in Seminar II. For him the metaphorical manoeuvre is akin to the magician’s sleight of hand. This violates the rule (in Hegel) that speech elevates the human above the animal. It is the case that for the subject to be constituted as self-conscious, some stimulus and response is required, but this is of a different order to the stimulus and response within the circuitry of any “cybernetic device” (which responds to stimulus and response in a similar fashion to the nervous system in an animal), because , for Lacan “a reaction is not a response”. [28]A response, in human communication, is an acknowledgement of an other’s existence and of their desire. It acknowledges an intersubjectivity that is constitutive of the subject that speaks and the subject that responds. By contrast to this, states Lacan: “If I press an electric button and a light goes on, there is a response only to my desire” [29] In this case, there is no intersubjective response, and that will remain the case, however elaborate the circuitry. What matters, on a human level is the production of intersubjectivity.

And in Seminar II Lacan again relates the cybernetic era to Hegel and to the question of Freudian energetics

“Mathematicians qualified to handle these symbols locate information as that which moves in the opposite direction to entropy. When people had become acquainted with thermodynamics. and asked themselves how their machine was going to pay for itself. they left themselves out. They regarded the machine as the master regards the slave - the machine is there. somewhere else. and it works. They were forgetting only one thing. that it was they who had signed the order form. Now. this fact turns out to have a considerable importance in the domain of energy. Because if information is introduced into the circuit of the degradation of energy. it can perform miracles. If Maxwell' s demon can stop the atoms which move too slowly. and keep only those which have a tendency to be a little on the frantic side. he will cause the general level of the energy to rise again. and will do. using what would have degraded into heat. work equivalent to that which was lost.” [30]:

Maxwell’s demon, in the post cybernetic era, is embodied in servomechanisms and computers. What then is the implication to the subject in relation to this new turn in the dialectic which produced the discourse of the machine?

So, it is not Lacan’s aim to endorse cybernetics, but rather to accept its reality within contemporary discourse. As with earlier discourse networks[31] (exact science, conjectural science) the subject’s relation to the symbolic will change, as the volume of symbolic material proliferates and as the media of its communication increase. The question then becomes, what kind of subjectivities are engendered within the discourse of cybernetics? How does the discourse of cybernetics structure the symbolic?

- ↑ Céline Lafontaine The Cybernetic Matrix of ‘French Theory’; Theory, Culture & Society 2007 (SAGE, Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, and Singapore), Vol. 24(5): 27–46

- ↑ [this is not without foundation, the 1951 Paris Congress on cybernetics was covertly funded by the C.I.A.. This was part of a larger program to ensure cultural influence in western Europe see Who Paid the Piper?])

- ↑ Note: For more on information theory and cybernetics as an ideological instrument see: Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan: From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Le´vi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38 (Autumn 2011), The University of Chicago + or read the annotation here]

- ↑ Lydia H. Liu: The Cybernetic Unconscious: Rethinking Lacan, Poe, and French Theory, Critical Inquiry 36 (Winter 2010),The University of Chicago

- ↑ Ian Hacking The Emergence of Probability

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954 1955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988

- ↑ The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis Paper delivered at the Rome Congress held at the Institute of Psychology at the University of Rome on September 26 and 27, 1953

- ↑ Note:In the Rome Discourse Lacan describes the relation as follows. On structural linguistics: “…the reference to linguistics will introduce us to the method which, by distinguishing synchronic from diachronic structurings in language, will enable us to better understand the different value our language takes on in the interpretation of resistances and of transference, and to differentiate the effects characteristic of repression and the structure of the individual myth in obsessive neurosis.”. Structural anthropology affords similar advantages:” “[I]t seems to me that these [psychoanalytical] terms can onlv be made clearer if we establish their equivalence to the current language of anthropology, or even to the latest problems in philosophy, fields where psychoanalysis often need but take back its own property.”

- ↑ Richard L. Warms & R. Jon McGee. Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology. An Encyclopedia Sage, 2013; Mark Poster, The Hegel Renaissance: Toward a Philosophical Anthropology, in Existential Marxism in Postwar France From Sartre to Althusser, Princeton University Press (1975)

- ↑ Alexandre Kojève (1902-1968), Introduction to the Reading of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit, Assembled by Raymond Queneau, Basic Books (1969).

- ↑ Alexandre Kojève (1902-1968), Introduction to the Reading of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit, Assembled by Raymond Queneau, Basic Books (1969).

- ↑ Kojève p4

- ↑ Seminar 1 147

- ↑ Although Lacan will invoke the cybernetic creatures built by Grey Walters and the “second guessing” robots like those built by Shannon and … these machines underline the central issue of the "homeostasis" section of the seminar.

- ↑ Hall, Calvin S. A Primer in Freudian Psychology. Meridian (1954)

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954-1955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. p79

- ↑ Seminar II (77-90)

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954-1955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988.(p40-52)

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 19541955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. P.539 54

- ↑ I. Hacking, The Emergence of Probability 10

- ↑ Bergson, H. The Creative Mind: An Introduction to Metaphysics. North Chelmsford, MA: Courier Corporation, 2012.

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954-1955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. (From the Entwurf to the Trandeutung) p. 117

- ↑ Here Lacan gives an interesting description of the functioning of a discourse network, as readers of Kittler would understand it. In Kittler, discourse is conditioned by the technical standards of the day; Lacan Takes up Hyppolite’s point that our understanding of what a machine is has changed in the era of cybernetics. See: Kittler, Friedrich A. Discourse Networks 1800/1900. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 1990.

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 19541955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. p.61

- ↑ Aka:Lacan. The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis

- ↑ Lacan. The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis p247

- ↑ Lacan. The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis p247

- ↑ Lacan. The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis p247

- ↑ Lacan. The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis p247

- ↑ Lacan 2, 84

- ↑ Here I use Kittler’s designation: Discourse Networks 1800-1900