The Fabulous Loop de Loop: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

The second issue, the question of fidelity of the image, was improved by allocating three functions on a two-inch thick tape. The larger part, running through the centre of the tape, would record the image and the margin at the top of the tape would record the audio, lastly a third track running at the bottom would contain the control data (regulating play back speed &c).<ref> Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. p56</ref> | The second issue, the question of fidelity of the image, was improved by allocating three functions on a two-inch thick tape. The larger part, running through the centre of the tape, would record the image and the margin at the top of the tape would record the audio, lastly a third track running at the bottom would contain the control data (regulating play back speed &c).<ref> Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. p56</ref> | ||

[[File:ampex.jpg|thumb|Ampex VR-1000 Videotape Recorder in use at Dallas television station KRLD, c. 1960.]] | |||

[ | |||

By 1960 the Ampex VR-1000 had introduced a system which integrated the recording of audio and video and which would provide the technological basis for more flexible and portable technologies in the coming decade.<ref> Peter Sachs Collopy, “Ampex trademarked the word Videotape and sold recorders ‘to all major telecasting networks, and to many network-affiliate and independent TV station in the U.S. and several foreign countries,’ including Canada, Japan, England, and Germany by 1958 and another 23 by 1961” Peter Sachs Collopy, Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015. Sachs Collopy Cites: Ampex, 1958 Annual Report, box 16, series 2, Ampex Corporation Records, pp. 9, 26; Ampex Corporation, 1961 Annual Report, box 16, series 2, Ampex Corporation Records, p. 13</ref> | By 1960 the Ampex VR-1000 had introduced a system which integrated the recording of audio and video and which would provide the technological basis for more flexible and portable technologies in the coming decade.<ref> Peter Sachs Collopy, “Ampex trademarked the word Videotape and sold recorders ‘to all major telecasting networks, and to many network-affiliate and independent TV station in the U.S. and several foreign countries,’ including Canada, Japan, England, and Germany by 1958 and another 23 by 1961” Peter Sachs Collopy, Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015. Sachs Collopy Cites: Ampex, 1958 Annual Report, box 16, series 2, Ampex Corporation Records, pp. 9, 26; Ampex Corporation, 1961 Annual Report, box 16, series 2, Ampex Corporation Records, p. 13</ref> | ||

Revision as of 15:06, 3 September 2020

THE PORTA PAK: SONY VIDEOROVER DV-2400 (1967) + SONY VIDEOROVER II AV-3400 (1970)

ONE

Video tape had been in development for decades before the introduction of the Portapak. It emerged from the development of audio tape, sharing a lot of its technological and institutional history. Even before the development of video tape, video cameras were used by the military – early video cameras were used as part of a weapons guidance systems – and were also adopted by the broadcasting industries – there was a pressing need for instantaneous playback of sporting and news events.[1]

The main disadvantages for the development of video tape technologies had been two-fold: the amount of tape the system consumed and the fidelity of the image. To begin with, the amount of tape that fed through the machines was considerable (thirty feet per second in earlier machines) [2] but once the “quadraplex recording” design was adopted [3] the Ampex VR-1000, which became the TV industries machine of choice by the late 1950s, consumed only “fifteen inches of tape per second—or half an inch per frame—fitting ninety minutes of video onto a reel fifteen inches in diameter.” [4] This brought the machine closer to portability, but it was still, by current standards, colossal and inordinately expensive for general use [5]

The second issue, the question of fidelity of the image, was improved by allocating three functions on a two-inch thick tape. The larger part, running through the centre of the tape, would record the image and the margin at the top of the tape would record the audio, lastly a third track running at the bottom would contain the control data (regulating play back speed &c).[6]

By 1960 the Ampex VR-1000 had introduced a system which integrated the recording of audio and video and which would provide the technological basis for more flexible and portable technologies in the coming decade.[7]

The parallel development of videotape and video-recorders had been taking place in Japan, which in the 1950s had imported the American Ampex VR-1000 systems for use in their own media. The cost and the size of the tape was reduced by Norikazu Sawazaki, who worked for Tokyo Shibaura Denki (Toshiba). His system (1957) wound the tape round a drum in a helix shape (at an angle) making it possible to record the information diagonally. Sawazaki’s system required two tape heads instead of four and reduced the amount of tape needed still further. [8] The Japanese motivation to compete with the American Ampex system was fierce and by 1959 Toshiba, Sony, Matsushita, and the JVC (Victor Company of Japan) all had functioning prototypes of video systems – all of which incorporated a helix system similar to the one Sawazaki had devised. The sticking point for the Japanese companies was that the American firm Ampex held the patent for many of the components,[9] but when Sony developed a transistorised VTR (Video Tape Recorder) Ampex permitted its use for non-broadcast use in exchange for Sony’s transistorized components in Ampex’s equipment.[10]

The next significant stage in the evolutionary graph toward the Portapak is the Sony PV-100 (1961). This helical scanning, transistorised VTR weighed 145 pounds and could be carried by two people. The system could now easily be placed on a boat, train or plane and was used outside of a “mass media” context, for instance as military training equipment and as inflight entertainment on commercial flights.

The Astrovision was a PV-100 built into the bulkhead at the rear of the American Airlines plane’s flight-deck . [11] By 1962 Ampex had developed the VR-1500 system, “small enough to be transported in the trunk of a car.” They suggested it could be used for educational purposes “[…] ideal for transmitting previously recorded educational programs over closed circuit systems and providing instant playback of ‘role playing’ and other classroom activities.” [12]

In 1963 this system was incorporated into the Ampex Signature Home Entertainment System (an elite media package exclusively offered through one department store). This move toward domestic consumption was countered in 1965 by the Sony TCV-2010 Videocorder, which was touted by Sony as “tape yourself TV”. This promise of easy access and personalisation, a closed-circuit system that provided the possibility of real-time engagement and instant playback, bringing us into the realms of self-produced media. Such technologies established a new political and cultural horizon for countercultural initiatives such as The Raindance Corporation and the magazine for “video freeks” Radical Software, but these systems were still beyond the pocket-book of the average American media-artist.

[image] “A New Pastime with a Big Future: Tape-It-Yourself TV,” Life, September 17, 1965, 57.[13]

In October 1965 the Korean artist Nam June Paik, with money from the John D. Rockefeller III Fund, bought a Sony TCV-2010 from the Liberty Music Shop in Manhattan. He immediately set to work, filming Pope Paul VI, who was visiting the United Nations, through the window of his taxi. June Paik played the tape at the Café Go Go in Greenwich Village that same night. “[A]s collage technic replaced oil paint, the cathode ray tube will replace the canvas” he declared at the time. This was a few months after Andy Warhol had received the rather more cumbersome Philips EL 3400 (weighing in at 100 pounds) as a promotional gift from the company. In Warhol’s’ 1965 film Outer and Inner Space we see Edie Sedgwick talking to her own video image. It is an early recording of the unnerving bodily experience of “telepresence” – whereby the subject apprehends themselves as other and the audience, by extension, is caught in the circuitry of identification. Almost as an artifice of the apparatus, in this early film-video work the element of feedback seeks to destabilise the integrity of the subject. You may remember Lacan’s fantasy of the cybernetic tortoise, where two machines are frozen in apprehension of the self in the other[14] so Sedgwick is caught in a moment of self-apprehension as other – caught in an intersubjective circuit. This decentering of the self could also be read through the lens of Gregory Bateson, to be removed from ones self and to be at the same time present makes one aware of the different levels of abstraction the self is constructed within. Could the video system which abstracts the real-time self and repositions to outside the body also be seen as a technologically advanced Structural Differential? Hasn't this subjective circuitry (the fabulous loop de loop) been a feature of feedback machines since the Vapour Engine? Isn't this an artefact of any feedback machine, which causes us to question the nature of consciousness and through its presence in the world (as a vapour engine, second-guessing computer or cybernetic pet) challenges our notions of how the self is constituted?

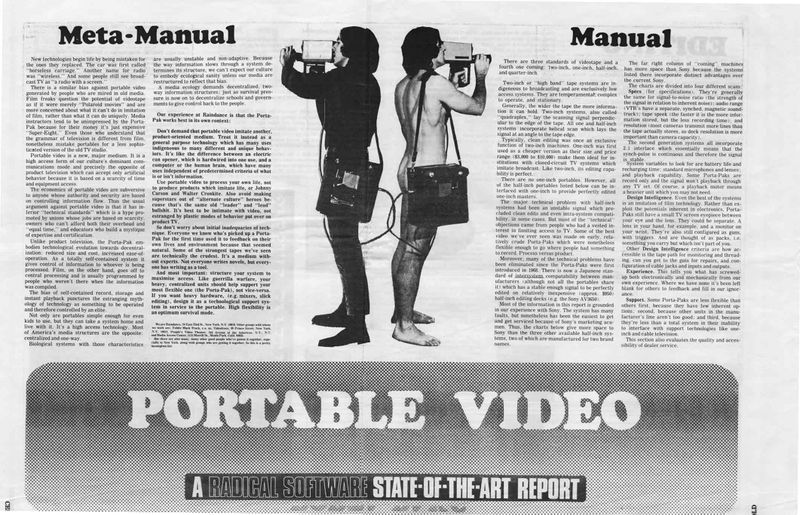

Sony’s battery powered VideoRover DV-2400 followed in 1967. The recording unit now weighed eleven pounds, with the camera weighing five. The system recoded on 20-minute CV video reels. This was the first of the “portapaks” – a generic name for the portable video systems produced by Ampex, Sony and Philips in the late 60s and early 1970s. The most successful to emerge was the Sony VideoRover II AV-3400 (1970) which recorded on 30 minute tapes and also afforded instant playback through the camera itself or through a monitor, it carried a standard format, EIAJ Type I tape which could be used on other brands of machine, and perhaps most importantly, it retailed for $1495.[15]

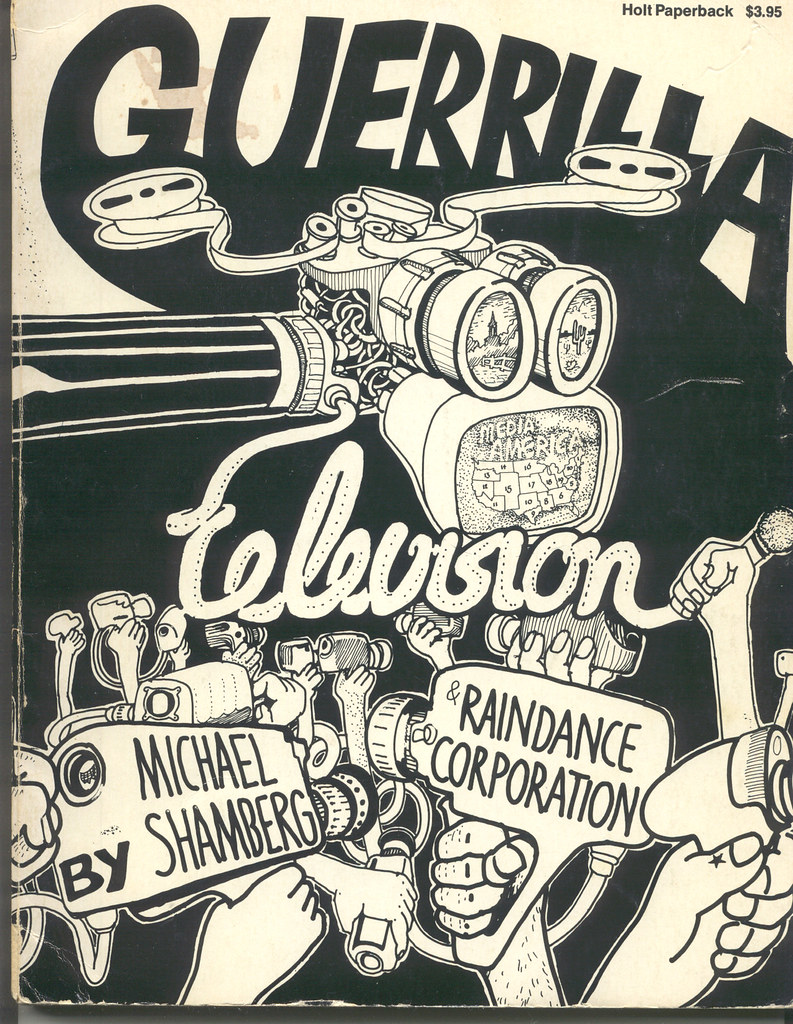

[Image] Sony VideoRover II AV-3400, 1970. Annotated photograph from Michael Shamberg and Raindance Corporation, Guerrilla Television (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971), section II, pp. 22–23.

Although variously used as a training tool, an educational aid, in the broadcasting industry and as a surveillance system in business, portable video equipment was about to find a new application in a cultural artistic revolution which embraced ecology, media, aesthetics, which will all refracted within this mirror of subjectivity, the portable video system.

TWO

Gregory Bateson's text Awake appeared in the fifth issue of Radical Software. It clearly annotated the errors in epistemology that threatened the future of Spaceship Earth in the second half of the twentieth century.

““[T]he ideas which dominate our civilization at the present time date in their most virulent form [are] from the Industrial Revolution.

a) It's us against the environment.

b) It's us against other men.

c) It's the individual (or the individual company, or the individual nation) that matters.

d) We can have unilateral control over the environment and must strive for that control.

e) We live within an infinitely expanding "frontier."

f) Economic determinism is common sense.

g) Technology will do it for us .

We submit that these ideas are simply proved false by the great but ultimately destructive achievement of our technology in the last 150 years. Likewise they appear to be false under modern ecological theory. The creature that wins against its environment destroys itself...”[16]

In 1970 there was nothing unusual about an ecological polemic appearing in a magazine devoted to the uses and maintenance of video systems. There was an abiding connection between the notion of an ecological system regulated by feedback and a technological system regulated by the same principle. And the parallel notions of "ecology" were not simply analogous, one does not serve as a representation of the other, they are systematically and structurally bound together, they are steps in a broader ecology of mind.

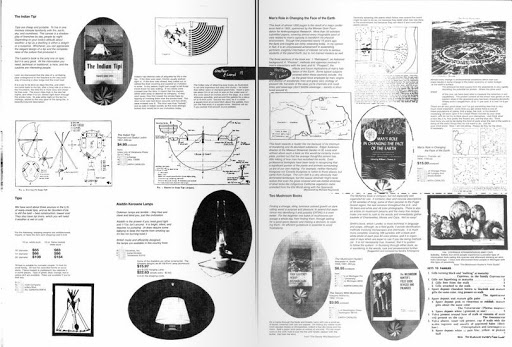

The model for Radical Software was Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, which was founded in 1968. The aim of the catalogue was to provide “access to tools” for the counterculture communities that sprung up in the second half of the 1960s. These communities, who sought independence from the industrialised world and from organised politics, also recognised the need to form a network with like-minded people. The Whole Earth Catalog provided such a network.

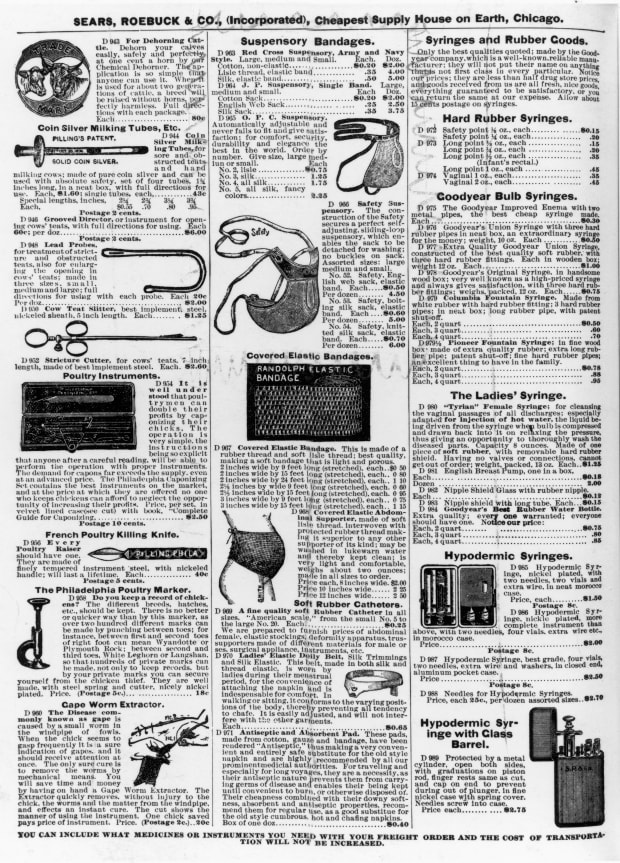

The Whole Earth Catalog provided channels through which self-sustaining systems could flow. Its models were, visually and practically, magazines such as the LL Bean Catalog (established in 1917) which gave access to information about products from hunting boots to fishing tackle and the Seers Roebuck and Co. Catalog “the cheapest supply house on Earth” (established 1893). These publications were characterised by a simple description of a product with the minimum of editorialising.[17]

Brand envisioned a “catalog of goods which owed nothing to the supplier and everything to the consumer.” [18] The Whole Earth Catalog contained a list of items and information “where to buy a windmill. Where to get good information on beekeeping. Where to lay your hands on a computer.” [19]

The Whole Earth Catalogue spoke to a new post-war subjectivity, in which alternative, appropriate localised technologies are worked with “hands-on”. So rather than preach a position, the Whole Earth Catalog presented a complete discourse in which environmentalism, consumerism, individual choice and technology were bound together. This was within a culture of thrift and ingenuity which encourages self-responsibility and agency.

It was within this context of self-sustaining ecological living, in which – to paraphrase Marshall McLuhan – each technological development represents and extension of human potential, that cybernetic ideas of ecology were built into the structure of the counterculture of the 1960s.[20] In a cybernetic system each element of that system is mediative, the subject can never be outside mediation.

Stewart Brand and the Whole Earth Catalogue provided channels through which cybernetic ideas of self-sustaining systems could flow. Core intellectual influences were Norbert Wiener, Buckminster Fuller and Marshall McLuhan. Gregory Bateson’s influence would be more evident in Brand’s next publication Co-evolutionary Quarterly (1974-1985), which followed Bateson's emphasis that human + environment constitute the whole system. Brand would remain a proselytiser of Bateson’s ideas up until Bateson’s death in 1980 and supported the last book Bateson was to publish in his lifetime, Mind & Nature. The ideals of self-sufficiency and self-sustainability had been narrated in cybernetic terms for the self-sufficient communities that were established from the mid-sixties on. [21] These attitudes and practices were re-coded into self-sufficient media ecologies as the 1970s approached, flowing through the output of media groups such as Raindance, TVTV (Top Value TeleVision), Ant Farm, The Woodstock Community Video and Videofreex.[22] In the era of second-order cybernetics the emphasis was on experiments in technologies of self – re-programming the system, programming the community. In the 1970s the "tools for living" which the counterculture had adopted in the 1960s were changing but the cybernetic epistemology remained in tact.

Within this context the conflated term ‘media ecology’ was developed in the pages of Radical Software in the early 1970s. Arlo Raymond attempted a definition in issue 1. Media ecology was, for him:”the study of media and communications and its affect on media and society.”[23] In STEM, Bateson took a more radical position, within a media ecology there is no distinction among technology, affect, and sociability.[24]

Bateson's ideas which crossed between ecology and media ecology, were seminal in the development of video art in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Bateson had been a prominent and active voice in debates about art and society throughout the 1950s[25] which shifted emphasis away from the artistic product (the painting or sculpture) and toward the context in which such an object is created. Central to Bateson's cybernetic aesthetics was self-reflexivity (by the artist and the audience of art) as a condition of artistic production. In 1957 Bateson and Marcel Duchamp joined Frank Lloyd Wright and Mayer Shapiro at the American Federation of Arts Conference. It was here that Bateson outlined a (media) ecological understanding of art. Schipiro represented the old-guard, regarding painting's foremost virtue to be its fundamental opposition to mass media, a view which was opposed by Bateson and Duchamp.[26] Duchamp delivered his now famous paper The Creative Act with Bateson presenting a text entitled Creative Imagination which was later published in STEM.[27]

The 1957 conference was noteworthy because it attracted a much larger audience than expected and because there was an insistence from those presenting, and the audience to discuss communication systems in relation to the arts. This was in the wake of an increased mass media presence and as the discourse on cybernetics became accessible to more people through (for instance) Norbert Wiener's books, a popularisation of Claude Shannon’s Information Theory as well as Bateson's own writing, including Communication and the Social Matrix of Psychiatry (with Jurgen Ruesch). Duchamp's paper sidesteps Schipiro's conservative position and holds the communicative and medial nature of art to be beyond the intention of the artist. The public decodes or "deciphers" the intentions of the artist and in so doing become creators of it.[28]

Bateson's paper is more assuredly cybernetic in nature. The Creative Imagination addresses the particular nature of artistic communication, which, as opposed to everyday communication, is a means of meta-level communication, art for Bateson is inherently self-reflexive, it communicates about communication. If Schipiro was interested in art as a form of resistance, or bulwark, to communication, a space immune from the perennial effects of communication, Bateson sees art as a play between different levels of communication, a play which makes those different levels visible.[29].

This position would be the central tenet of early video art and the media theory discussed in Radical Software and would be a formative influence on artists such as Dan Graham (profoundly influenced by Bateson and Radical Software). For Bateson, aesthetic awareness allows for an understanding of the process by which it is possible to acquire knowledge. This produces the grounds on which a communications system is framed to be made visible, which for a generation of artists in the 1960s and 70s situated art as an inherently self-reflexive, self-critical and context-critical endeavour. For Bateson communication produces context and further reflection on the production of that context.[30]

This medial reading of aesthetics is in line with the valorization of creativity which was part of the post WWII's reinvention of the liberal subject: the self-reflexive self, constituted within media circuits (media-ecologies), which Bateson and Ruesch's Communication and the Social Matrix of Psychiatry had concerned itself. Here the self is beyond the individual subjectivity of ‘I’, mind is "immanent in the larger system, man plus environment. Communication is the "substance of common being".[31] Central to Bateson’s understanding of art was a conception of aesthetics as a form of ‘deutero-learning’ which deals with “context and classes of context” (as opposed to proto-learning which deals with “narrow fact”).[32]

When artistic practice and discourse finally adopted ideas of self-reflexivity and radical mediality in the late 1960s and early 1970s it was largely because of the influence Bateson had exacted on the counterculture from the 1960s on. Bateson’s vision of 'mind' as unbounded within a field of technological communication found resonance with a generation raised on the mass media and had also felt the alienating affects of that media. Many had also experienced some dissolution of the essential self through exposure to hallucinogenics, which provided a model demonstration of a self which is medial and co-exensive Gregory Bateson himself had been a participant in the CIA’s LSD experiments in the 1950s. The drug was administered to him by CIA agent Harold Abramson. In 1959 Bateson helped arrange for his friend, the beat poet Allen Ginsberg, to take the drug at a research program located off the Stanford campus (see chapter E-Meter).[33] This was the same programme at which Ken Keasy and Stuart Brand met. Keasy and Brand went on to organise the multi-media Trips Festival in 1966. [34] In the following year Kesey and his Merry Pranksters boarded the magic bus and Brand (a semi-detached merry prankster) founded the Whole Earth Catalog.[35]

Videofreex Cc. 1973. Relaxing with a Portapak

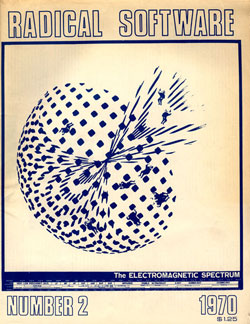

The Raindance Corporation was established as a platform for media activism and as a think tank – a radical alternative to the RAND Corporation15.[36] Radical Software was started by Beryl Korot, Phyllis Gershuny, and Ira Schneider.[37] It provided a forum for discussion, the decimation of information and the formulation of media theory as well as a platform for established writers and theorists. The founders and contributors to Radical Software were largely artists working with the new Porta Pak video system which became accessible at the end of the 1960s. At the cost of $1500 it was not cheap, but it was in the range of many more users than had previously been the case, and could be easily acquired by collectives. Tapes were easy to distribute, and could be re-used and copied. The second technological revolution came in the form of cable (CATV). Ralph Lee Smith’s article The Wired Nation (1970) heralded a new media revolution which would accord access to the contact of “newspapers, mail service, banking and shopping facilities, data from libraries and other storage centres, school curricula and other forms of information too numerous to specify. In short, every home and office will contain a communications centre of a breadth and flexibility to influence every aspect of private and community life.”[38] The artists Frank Gillette and Ira Schnider, in the first issue of Radical Software (1970), recognised that the combination of cable hooked up to portable video equipment would break the ecology of the mass media, radically changing the subject positions of producers and consumers of media.[39] CATV, like CCTV, was a closed circuit system extended to a very great extent allowing for a feedback loop of communication between participants over a great distances.[40] The recursive structure of this system could take the form of shared communication and could equally create positive feedback (noise). Both feedback as noise and negative feedback as a system of control offered political and artistic potential which the community around Radical Software were keen to exploit.

Raindance and Michael Shemberg’s publication Guerrilla Television (with graphics by architect-design collective Antfarm) (1971) would identify mainstream ‘Media America’ as designed to minimise such feedback, allowing only a one-way flow between sender and receiver. This resulted in an accumulation of cultural power into the hands of corporate America. Portable video systems, along with access to cable technology, would help redress this imbalance. A principle platform in the pages of Radical Software, therefore, was to lobby for the open uses of CATV (the appointment of licences began in 1970). Between 1968 and 1972 cable operators offered support to community based projects, this was exploited by a wave of artist-activist initiatives and underwritten by New York State Council for the Arts (which in 1970 increased its budget to the arts from $2m to $20m). Initiatives by artists and artist collectives also received support from private foundations. The emphasis and motivation on the community of video artists working for and around Radical Software was on community based media projects and ecological activist projects (the annual Earth Day began in 1970). [41] Paul Ryan had worked for Marshall McLuhan whilst McLuhan was visiting professor at Fordam University (1967-1968). McLuhan gave Ryan, Frank Gillette and Nam June Paik access to Sony Porta Paks that McLuhan had received from from Sony (he had little practical use for them). [42]

Ryan and Gillette, along with their colleague Roy Skodnick [43] would become key architects in the discourse of video-art-activism as it emerged from the ecological movement. They produced seminal works, texts and forums for theory and practice (often through the offices of Raindance and Radical Software). Radical software combined pragmatic advice of how to work the technology with an emergent theoretical framework which considered the implications of that technology on future culture and society.[44] Ryan was inspired by McLuhan at his most optimistic, who in Understanding Media, had posited that electronic media could result in “the ultimate harmony of all being” [45], this, in Radical Software was tempered with a politically critical approach which advocated “Cybernetic Guerrilla Warfare”[46] which challenged the "top down" monopolies of Media America.

If the Portapak as a piece of technology encouraged a radical new form of social-media and media collectivity, it also allowed for the creation of artworks which made the individuals place within a media circuitry visible. Paul Ryan’s Everyman’s Mobius Strip (1969), Frank Gillette and Ira Scheider’s Wipe Cycle (1968),and Dan Graham’s TV Camera/ Monitor Performance (1971); Frank Gillette’s, Video: Process and Meta-Process (1973) all performed the logic of the self as co-extensive to a given system =(nervous system, system, environment). As Skodnick was to reflect years later, social movements and media movements were converging “[…] with Bateson as principle guide to the complexities of nature and culture. [Frank] Gillette did it, Randy Sherman did it, and apparently [Dan] Graham did it too. Anyone who happened to get hold of a portable video system at the time immediately overloaded on circuits, playback, feedback and fabulous loop de loop.” [47]The Porta Pak, Skodnick observed, was a “beautiful system” that not only allowed the user to “ track social behaviour but also to see how social behaviour is framed […] TV dissolved into a more plastic language.” Skodnick continues, “ [T]here was a full-bore media war of information then, and visual information was fully up for grabs. We could put ourselves in it, see ourselves seeing ourselves, and even enter the jouster with the ‘News cycle’ emptying out, as was demonstrated in [Gillette’s] Wipe Cycle.” Such was the “radical ecology of Radical Software”. [48] Paul Ryan: “Video itself mutated from a counter cultural gesture to an art genre. When video was principally a countercultural gesture, it held the promise of social change unmediated by the art world. Now, whatever promise of social change video holds is mediated by the art world. This is a significant difference. People unfamiliar with the mutation find it difficult to appreciate the unlimited sense of possibility that early video held.” It was in this milieu that Bateson's ideas made their transition from the sphere of ecology into media art. For Bateson, in the realms of anthropology, psychiatry, ecology and aesthetics the self-reflexive subject is central, the medial subject who recognises their place within a hierarchy of abstraction The progression from Behaviour, Teleology & Purpose, the McCulloch-Pitts model, Norbert Wiener’s negentropy and, Ashby’s Homeostat to the emerging ecology movement and its abiding connection to media ecology can be found in Bateson's 1968 essays Effects of Conscious Purpose and Human Adaptation [49] and The Roots of Ecological Crisis[50].[discussed in the previous chapter] In these Bateson returns to the beginning of the fabulous loop de loop, and to the evolutionary models that had excited Samual Butler's imagination a century before, to the 'vapour engine' which, even on this side of the fabulous loop de loop, serves again as a model for evolution.

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015. p50

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s University of Pennsylvania, 2015. p74

- ↑ (which mounted four heads on a drum which scanned the two inches-wide tape as well as its length,

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015. p75

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy:“[The Ampex] VR-1000, for example, weighed 1465 pounds and cost $45,000 in 1956”. Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015. p77

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. p56

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy, “Ampex trademarked the word Videotape and sold recorders ‘to all major telecasting networks, and to many network-affiliate and independent TV station in the U.S. and several foreign countries,’ including Canada, Japan, England, and Germany by 1958 and another 23 by 1961” Peter Sachs Collopy, Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015. Sachs Collopy Cites: Ampex, 1958 Annual Report, box 16, series 2, Ampex Corporation Records, pp. 9, 26; Ampex Corporation, 1961 Annual Report, box 16, series 2, Ampex Corporation Records, p. 13

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015 p79

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015 p 80

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015 p 81

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015 p 83

- ↑ Ampex, 1963 Annual Report, 7.In Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015 p.84

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015 p.84 (By now the system used the half-inch CV [consumer video] format which used the hexical scan and the “frame rate” was reduced through a “skip field” function.)

- ↑ See chapter – The Tortoise and Homeostasis

- ↑ Peter Sachs Collopy, The Revolution Will Be Videotaped: Making a Technology of Consciousness in the Long 1960s. University of Pennsylvania, 2015 p93

- ↑ Gregory Bateson Radical Software Issue 5 Volume 1, 33 3Bateson STEM. 87

- ↑ Having said that, the politics of many of the contributors tended toward a libertarian distrust of big government [Andrew G. Kirk Counterculture Green: The Whole Earth Catalog and American Environmentalism; University Press Kansas, 2007, p 21] and the contrast between the New left, (which fought for institutional reform) and the counterculture (which advocated individualism and a withdrawal from institutional politics) is substantial [Fred Turner From Counterculture to Cyberculture

- ↑ Brand in Andrew G. Kirk Counterculture Green: The Whole Earth Catalog and American Environmentalism; University Press Kansas, 2007, p1

- ↑ J. Baldwin The Essential Whole Earth Catalog | cited in Andrew G. Kirk: Counterculture Green: The Whole Earth Catalog and American Environmentalism; University Press Kansas, 2007, p 21

- ↑ Understanding Media | McLuhan's medium theory was influenced by Bateson's Communication and the Matrix of Psychiatry and Wiener's Cybernetics

- ↑ Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture

- ↑ David Joselit Feedback: Television Against Democracy, MIT Press 2007

- ↑ Arlo Raymond, Media Ecology Radical Software Issue 1

- ↑ Bateson STEM. 87

- ↑ For instance, Bateson was a member of the Western Roundtable on Modern Art in San Francisco in 1949, which included Marcel Duchamp.

- ↑ William Kaizen, Steps to an Ecology of Communication: Radical Software, Dan Graham, and the Legacy of Gregory Bateson: Art Journal, Vol. 67, No. 3 (FALL 2008), pp. 86-107, p92

- ↑ M.Duchamp The Creative Act, ART-news Vol. 56, no. 4, 1957

- ↑ M.Duchamp The Creative Act, ART-news Vol. 56, no. 4, 1957

- ↑ Gregory Bateson The Creative Imagination Stem p

- ↑ William Kaizen, Steps to an Ecology of Communication: Radical Software, Dan Graham, and the Legacy of Gregory Bateson: Art Journal, Vol. 67, No. 3 (FALL 2008), pp. 86-107 pp. 93-94

- ↑ Bateson, in William Kaizen, Steps to an Ecology of Communication: Radical Software, Dan Graham, and the Legacy of Gregory Bateson: Art Journal, Vol. 67, No. 3 (FALL 2008), pp. 86-107, p94

- ↑ Bateson, Mind and Nature, 156

- ↑ Marks 1979:120

- ↑ Turner; From Counterculture to Cyberculture, University of Chicago Press, 2008

- ↑ Bateson, through his friendship with Alan Watts, also took an interest in Zen Buddhism as the model for a non-occidental, radically discentered, non-Cartesian philosophy STEVE P. HEIMS: Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 13 ; GREGORY BATESON AND THE MATHEMATICIANS: FROM INTERDISCIPLINARY INTERACTION TO SOCIETAL FUNCTIONS 1977, 141-159

- ↑ The Research ANd Development arm of the industrial, military, academic complex)

- ↑ All past issues are archived here https://www.radicalsoftware.org/e/index.html

- ↑ Lee Smith, in Joselit's Feedback, Television Against Democracy, MIT, 2007 p91

- ↑ Radical Software, Issue 1. 1970

- ↑ David Joselit's Feedback, Television Against Democracy, MIT, 2007 pp 96-97

- ↑ David Joselit Feedback, Television Against Democracy, MIT, 2007 p98

- ↑ P. Ryan; A Genealogy of Video; Leonardo, Vol. 21, No. 1, 1988, pp. 39-44

- ↑ – nicknamed the “Bateson Boys” because of their fondness for Bateson’s theories

- ↑ Paul Ryan, Radical Software issue 4, 1971.

- ↑ McLuhanUnderstanding Media

- ↑ Paul Ryan, Radical Software Issue 4

- ↑ Skodnick: Radical Software and the Legacy of Gregory Bateson Author(s): Paul Ryan and Roy Skodnick; Art Journal, Vol. 68, No. 1 (SPRING 2009), 113

- ↑ Skodnick Radical Software and the Legacy of Gregory Bateson Author(s): Paul Ryan and Roy Skodnick: Art Journal, Vol. 68, No. 1 (SPRING 2009),113

- ↑ Bateson,StEM 446

- ↑ Bateson StEM 494