SIMULACRUM – CYBERNETICS – BAUDRILLARD: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

ESSAY | ESSAY | ||

Revision as of 11:58, 18 November 2020

ESSAY

DEPART FROM ZERO–2.0[1]

CAMERA LUCIDA

In April 2006 I attended a lecture by Dr Erna Fiorentini of the Max Plank Institute, Berlin, in which she demonstrated a camera lucida. [2]

The device is a four-sided prism that works on a similar principle to a periscope (but this contraption allows you to look down and across as opposed to up and across).

Instructions for use: take a pen and paper and place them on the horizontal surface of the table on which the machine is set up. Look down into the lens of the machine and you will see the image that your eyes would normally see if you looked straight ahead, you will also see the superimposed image of your own hand and the pen you are holding, you trace the image you see onto the paper. You will see the lines you have drawn through the ghostly image of your hand and pen. The machine has a vertiginous effect as the distance between the outside world and the inside of your mind are collapsed into the same space, the action is going on, it seems, only in your eye and mind. To make a good drawing, however, it is necessary to suspend thinking about the thing you are drawing and simply trace the contours of this image inside your eye. In this respect you become an extension of the machine. Two things spring to mind: the first is that the realms of the imaginary and the symbolic seem to be problematrized by this device and secondly, the difference between what the eye sees ‘out there’ and what is recorded on the paper (the interpretive function of drawing) is collapsed. The camera lucida, in making the human body and the machine a single machine, is the perfect agent of the simulacrum because it abolishes difference.

ZERO

In The Precession of the Simulacrum Jean Baudrillard writes, of the abolition of the sovereignty of the signified,[3]

the annulment of the arbitrary link between the (acoustic) signified and the (conceptual) signifier – a link which, in Saussurian linguistics, is established by the difference between those two elements which make the sign – he is not only addressing the conditions of the order of the simulacrum, an order in which the copy has no original, but also a parallel development, that of the order of the code whereby there is no longer a distinction between the message and the medium which carries it. [4] In the order of the code the same logic prevails as in the order of the simulacrum, namely that no referent predicated on difference is required to produce a sign – in both orders there is no necessity for an original.

To explain this Baudrillard follows a similar strategy to Lacan. Just as Lacan avoids directly addressing the fathers of modern cybernetics, preferring to direct his attention to the architects of speculative science, at the beginning of The Precession’ Baudrillard invokes the notion of the simulacrum to challenge two key notions of identity that are predicated on difference and which pre-date the notion of difference central to the “the linguistic turn”, the ideal and the negative. There are two types of image that correspond to these notions of identity; the icon (which is associative, bearing the likeness, but different, to the ideal which it depicts) and the index (which is consecutive, pointing to the existence of the thing away from the image, a negative definition.)[5]

The simulacrum, by contrast, is itself opposed to representation and stems from “the utopia of the principle of equivalence, from the radical negation of the sign as value.” [6]In the order of the simulacrum the economy of the sign is negated. For Baudrillard, therefore, the real was always fugitive as both notions of identity collapse under the weight of the abolition of difference. Again, we are invited to contemplate a periodization; in Baudrillard’s history we see the progressive unmasking of what is not there and was never there, the slow denuding of the exchange value of the sign, as we move through four stages of the precession’s orbit (which begins with the belief in “the image as a reflection of a profound reality” and ends with to the realization that the image has “no relation to reality whatsoever”). [7]

Finally we come to the tragic realization that the exchange we were promised carries no guarantee,[8] the equivalence between the sign and the real, always implicit in the deal between the sign and its referent, has in fact given way to the “utopian principle of equivalence”, the radical negation of the sign as value per se. I use the word “tragic” [9] because Baudrillard’s narrative does indeed tell a story of the progressive loss of faith in the real; from the faith in the “good appearance” of the sacramental order, to the suspicion that a profound reality is masked (“denatured”), to the pretence that a profound reality exists beneath the mask of the image (“it plays at being an appearance”), and finally to the realization that the image has no relation to reality at all. [10]

ONE

(“YOU are the information, you are the social, you are the event, you have the word &c.”) [11]

Baudrillard repeatedly aligns this abolition of difference with the codes of DNA, linguistics and computation that collectively establish the ontology of equivalence. Our forking path must now make its second junction with media theory, because in the penultimate section of The Precession of the Simulacrum (“The End of the Panopticon.”) Baudrillard takes a cork screw punch at Foucault’s panopticon (criticizing the tenability of the Foucault’s notion of discourse) and Debord’s society of the spectacle (which emphasizes the passivity of the spectator.)

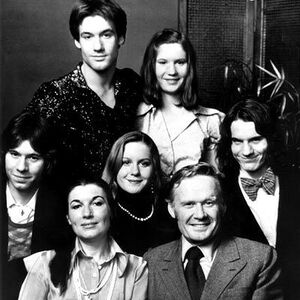

Baudrillard’s engagement with the subject of Reality TV best exemplifies the divisions between the Situationist and Foucauldian perspectives and his own, And perhaps this is because, for Baudrillard, neither Debord or Foucault recognize the potency of “the pleasure in the microscopic simulation that allows the real to pass into the hyperreal” which disrupts the regimes of both regulatory discourse (negotiated power relations at the level of discourse) and the idea of the society of the spectacle (the consumption of media as the final end of media in industrial society.) Baudrillard cites the reality TV show An American Family (1973), which traced the daily life of the Loud family, ostensibly an archetypal well-to-do-all-American-family (five kids, secure jobs, full medical and dental &c…) as the sacrificial victims of this new TV format which is an “exhumation of the real in its fundamental banality.” [12]

Baudrillard: “TV Verité. A term admirable in its ambiguity, does it refer to the truth of the Loud family or to the truth of TV? In fact, it is the TV that is the truth of the Louds, it is the TV that is true, it is TV that renders true. Truth that is no longer the reflexive truth of the mirror, nor the perspectival truth of the panoptic system and of the gaze, but the manipulative truth of the test that sounds out and interrogates, of the laser that touches and pierces, of computer cards that retain your preferred sequences, of the genetic code that controls your combinations, of cells that inform your sensory universe. It is to this truth that the Loud family was subjected by the medium of TV, and in this sense it amounts to a death sentence (but is it still a question of truth)." [13]

Baudrillard (the great abolitionist) sees reality TV as the “the abolition of the spectacular” whereby, following the logic of the abolition of difference, “the position between the passive and the active is abolished”, this heralds the arrival of the performer/consumer, caught in the feedback loop of the media where there is no space for reflection just “pure flexion or inflexion”, the final end of a perspective that could conceive of a space outside the media. “YOU are the information, you are the social, you are the event, you have the word &c.” [14] Reality TV, which can only show us the reality of TV, is the conclusion of the dissolution of difference that seemed to guarantee an exchange with the real. And this dissolution of difference leaves us with a universe that is indeed digital all the way down; encompassing our social, political and biological lives.

ZERO

The Precession of the Simulacrum is one instance in contemporary theory which leads us to the investigation of a world in which information is the common substratum of all matter a system of formal relations which in Gregory Bateson’s words “go for natural selection, which go for internal physiology, which go for purpose, which go for a cat trying to catch a mouse, which go for me picking up the salt cellar” [15] and which taken together form an “ontology of the code”. While Wiener and Bateson might be seen as the utopians of the order of the code, Lacan and Baudrillard might be seen as its critics, but this criticism is always charged with the irony that the computational paradgm itself forms the tools of argumentation against it, which is why, when reading Baudrillard in particular, one can always hear, somewhere in the background, the lonely tolling of a bell.

When the economy of the sign is annulled what form of value does representation have? The answer can only be that we can forget about representation, in the sense of something standing in for something else, the advocacy of the sign, so to speak, because in the order of the simulacrum it is Information itself which represents itself to itself, generates itself within itself, because in the order of the simulacrum everything is made of the same stuff, speaks an un-differentiated language, all the way down. “ It is because the code has been miniaturized. Objects are images, images are signs, signs are information, and information fits on a chip. Everything reduces to a molecular binarism. The generalized digitality of the computerized society.” [16]

ONE

Lyotard: “Along with the hegemony of computers comes a certain logic, and therefore a certain set of prescriptions determining which statements are accepted as “knowledge” statements.” [17]

I’ve been describing a precession, an orbit (or even a spinning) around the subject of cybernetics, but more particularly my question has been to what degree cybernetics can be understood as ontological. We have seen that the claim that cybernetic theory provides the key to an understanding everything is something more than a linguistic coup de grace executed by Norbert Wiener in 1947. For such a move to be effective it had to be informed by a number of factors including developments in the understanding of language, changing scientific methodologies, technological developments and philosophical investigations into the nature of identity. In the Fabilous Loop de Loop I have outlined a series of periodizations which overlap each other, each locates the beginnings of this shift at different stages and at different registers (the various registers of science, technology, language analysis, media theory and philosophy). Taken together these arguments form a convincing case for cybernetics’ claim to ontological status (or at the very least hegemonic status), but this is far from a triumphant conclusion. From the principle that all living things are encoded it follows that all human and animal activity is predicated on the same code, the code lays its grid over language, human assembly in all its social, cultural and political manifestations (all generated and regulated by feedback – ecologies of information, ecologies of language, ecologies of nature &c). One could look for an origin outside of time, in the age of myth, or at the helm of the Kybernetes’ boat, in the development of speculative science, at the moment of invention of the iconic image. The American architects of this worldview tend to look on the advantages of this development, its critics tend to emphasize the horrors it creates: Baudrillard’s desert of the real, Kittler’s media feedback system where the ‘noise’ becomes the content, Deleuze’s control societies in which the subject is encoded and de-territorialized or Lyotard’s vision of the postmodern condition in which scientism is the only legitimizing agent, where only performance, caught in a feedback loop, legitimizes knowledge.

My aim has been to chart my own narrative, to come to some understanding of what is at stake when one claims that the universe is digital all the way down. I wanted to shift my own perspective from the ‘Dr Strangelove’ world I had previously assigned to the subject of cybernetics – a world in which gentlemen in white lab coats attach osmotic pumps to the tails of rats, who play with electronic tortoises, who gleefully imagine the radically efficient mechinization of the human body in order to project it into space. [18] But, of course, the implications of the institution of the cybernetic paradigm reaches further than the increased instrumantilization of the human body – in the face of which at least one can take an ethical position (for instance, “this far and no further” or “yes, let’s leave this wretched planet and, equipped with modified bodies, head out for the final frontier.”)

Perhaps what is more important, and challenging, is the realization that, irrespective of how many cybernetic prostheses our bodies contain, our understanding of our bodies is inescapably that of the encoded body. And this is the most radical claim of the new regime, that our bodies are already machines, and that we have been laboring under the misconception that they were something other than information machines that interact and share information with other machines. Furthermore, the subject is subjected to the order of the code and is recognized only to the degree it is encoded biologically and socially – the codes that allow for our reproduction and the codes that give access or bar us from particular spaces or sites of information – from gated communities to ATM machines. […]

- ↑ This is an extended and reedited version of a text with the same name (Depart from Zero) published in Steve Rushton, Masters of Reality, Sternberg Press, 2011.

- ↑ Fioreneti, E. Lecture: “Varying Points of View, Negotiations between vision and representation in history.” Universiteitsmuseum, Utrecht, April 2006; The original design of the camera lucida was published by William Hyde Wollaston (1766-1828) in 1807.”

- ↑ Baudrillard, Jean, “The Precession of the Simulacrum”, Simulacra and Simulation, Michigan Press, 1994 (French edition 1981)

- ↑ Shannon and Weaver Information Theory

- ↑ The first (the ideal/iconic) veils/reveals the identity of that which is itself (“A=A”) and the second, (the indexical) veils/reveals identity in difference (“X is not Y”.)

- ↑ Baudrillard, Jean, “The Precession of the Simulacrum”, Simulacra and Simulation, Michigan Press, 1994 (French edition 1981) p. 524

- ↑ Baudrillard, Jean, “The Precession of the Simulacrum”, Simulacra and Simulation, Michigan Press, 1994 (French edition 1981)p. 524

- ↑ Baudrillard, Jean, “The Precession of the Simulacrum”, Simulacra and Simulation, Michigan Press, 1994 (French edition 1981) p. 524

- ↑ There is a notable relation in Baudrillard between the essence of literary tragedy, death, and the simulacrum, but paradoxically death is also hypostasized in the simulacrum- the mummy is repaired, restored &c.

- ↑ Baudrillard, Jean, “The Precession of the Simulacrum”, Simulacra and Simulation, Michigan Press, 1994 (French edition 1981)p. 524

- ↑ Baudrillard, Jean, “The Precession of the Simulacrum”, Simulacra and Simulation, Michigan Press, 1994 (French edition 1981) p. 540

- ↑ Particularly poor old Mrs. Loud “[The] ideal heroine of the American way of life, it [sic], is, as in ancient sacrifice, chosen in order to be glorified and to die beneath the flames of the medium, a modern fatum” ibid., p 539

- ↑ Baudrillard, Jean, “The Precession of the Simulacrum”, Simulacra and Simulation, Michigan Press, 1994 (French edition 1981)p. 540

- ↑ Baudrillard, Jean, “The Precession of the Simulacrum”, Simulacra and Simulation, Michigan Press, 1994 (French edition 1981) p. 540

- ↑ Gregory Bateson in: For God’s Sake, Margeret! CoEvolutionary Quarterly, June 1976, Issue no. 10, pp. 32-44

- ↑ Massumi, B., “Realer Than Real, The Simulacrum According to Deleuze & Guattari,” Copyright issue 1, 1987

- ↑ Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, Minnesota Press, 1984 (1979), p.4

- ↑ Clynes, Manfread E. & Kline, Nathan S., “Cyborgs and Space”, Astronautics, September 1960, p., 26-27/74-76