Play Like an Idiot: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

Lacan’s seminar on the Purloined letter, which takes up part of Seminar II, was a public manifestation of a dialogue that had been going on for some time, principally with the Author of What is Cybernetics? (1954) – who was also the co-organiser of the Paris congresses on cybernetics (1950-1951) – Georges Theodule Guilbaud. | Lacan’s seminar on the Purloined letter, which takes up part of Seminar II, was a public manifestation of a dialogue that had been going on for some time, principally with the Author of What is Cybernetics? (1954) – who was also the co-organiser of the Paris congresses on cybernetics (1950-1951) – Georges Theodule Guilbaud. | ||

Guilbaud’s “Lectures on the Principal Elements in the Mathematical Theory of Games” had earlier made explicit reference to Edger Allan Poe’s Purloined Letter. In various other texts Guilbaud notes the game of odd & even (ones & twos), mentioned in Poe’s tale as equivalent to Matching Pennies, the game cited for similar analysis by Neumann and Morgenstern in Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944).4<ref>Liu, Lydia H. ''The Freudian Robot: Digital Media and the Future of the Unconscious''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011. p.301</ref> In Guilbaud’s lecture “Pilots, Planners, and Gamblers: Toward a Theory of Human Control”, Guilbard posits the idea that the game of Odds & Evens presents the possibility of the mathematicians’ dream – the pure game ((jeu pur). In this lecture Guilbaud also cites an earlier work by Jacques Lacan, Logical Time and the Assertion of Anticipated Certainty, (1945) which discusses Neumann and Morgenstern’s Theory of Games and Economic Behavior no more than a year after its publication.

5F<ref>Liu, L. H. ''The Freudian Robot: Digital Media and the Future of the Unconscious''. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011.301 </ref> For Lacan the game theory of Neumann and Morgenstern, the communications theory of Shannon and the notion of the (theoretical) universal machine conceived by Turing allowed for a wholly up-to-date conception of the unconscious.<ref> By 1954, as Lacan opened his seminar, a particular kind of machine had emerged that both illustrated and performed the formation of the subject in exterior relation to the machinery of the game. It was specifically finite state automata such as the SEquence Extrapolating Robot (SEER) that allowed Lacan to claim that “the symbolic world is the world of the machine.” | Guilbaud’s “Lectures on the Principal Elements in the Mathematical Theory of Games” had earlier made explicit reference to Edger Allan Poe’s Purloined Letter. In various other texts Guilbaud notes the game of odd & even (ones & twos), mentioned in Poe’s tale as equivalent to Matching Pennies, the game cited for similar analysis by Neumann and Morgenstern in Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944).4<ref>Liu, Lydia H. ''The Freudian Robot: Digital Media and the Future of the Unconscious''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011. p.301</ref> In Guilbaud’s lecture “Pilots, Planners, and Gamblers: Toward a Theory of Human Control”, Guilbard posits the idea that the game of Odds & Evens presents the possibility of the mathematicians’ dream – the pure game ((jeu pur). In this lecture Guilbaud also cites an earlier work by Jacques Lacan, Logical Time and the Assertion of Anticipated Certainty, (1945) which discusses Neumann and Morgenstern’s Theory of Games and Economic Behavior no more than a year after its publication.

5F<ref>Liu, L. H. ''The Freudian Robot: Digital Media and the Future of the Unconscious''. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011.301 </ref> For Lacan the game theory of Neumann and Morgenstern, the communications theory of Shannon and the notion of the (theoretical) universal machine conceived by Turing allowed for a wholly up-to-date conception of the unconscious<ref>Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 19541955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. (Seminar on the Purloined Letter) p?</ref> By 1954, as Lacan opened his seminar, a particular kind of machine had emerged that both illustrated and performed the formation of the subject in exterior relation to the machinery of the game. It was specifically finite state automata such as the SEquence Extrapolating Robot (SEER) that allowed Lacan to claim that “the symbolic world is the world of the machine.” | ||

In the case of the tortoise and in the finite state automata, the same relation is established. Both machines – in their encoding and in their production of symbolic material (be they conscious or not) – demand an encounter with an other. | In the case of the tortoise and in the finite state automata, the same relation is established. Both machines – in their encoding and in their production of symbolic material (be they conscious or not) – demand an encounter with an other. | ||

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

Jacques Lacan’s Seminar II comes half a decade after French elite intellectuals were introduced to game theory, cybernetics and communication theory. | Jacques Lacan’s Seminar II comes half a decade after French elite intellectuals were introduced to game theory, cybernetics and communication theory. | ||

In Odd or even? Beyond Intersubjectivity, Lacan explains the function of a machine very similar to SEER, Lacan got participants to play odd or even (matching pennies) and to record the results (win or lose) as + or – symbols. <ref>Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis | In Odd or even? Beyond Intersubjectivity, Lacan explains the function of a machine very similar to SEER, Lacan got participants to play odd or even (matching pennies) and to record the results (win or lose) as + or – symbols. <ref>Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954 1955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. (Seminar on the Purloined Letter) p*</ref> | ||

The events follow a similar narrative to the one described by playing Shannon & Hagelbarger’s SEER. | The events follow a similar narrative to the one described by playing Shannon & Hagelbarger’s SEER. | ||

Revision as of 15:50, 20 July 2020

SEER (SEquence Extrapolating Robot) – McCULLOCH – LACAN

McCulloch-Pitts: “Purposive behavior depends upon how output affects input which, in turn, depends upon a nervous system whose organization can be treated statistically.”

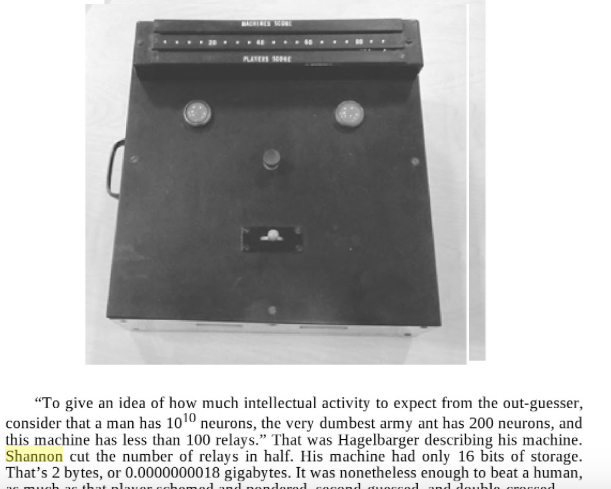

The SEER (SEquence Extrapolating Robot) was developed by Claude Shannon & David Hagelbarger at the Bell Labs in the early 1950s. Its aim was to outplay a human in the game of odd or even (matching pennies / ones and twos). To personalize the playing experience the machine was made to resembled a human face with two lights for eyes, a button for the nose and a red toggle switch forming a tongue sticking out. This is in keeping with the playfulness of Shannon’s other machines, particularly the “ultimate machine” (1952), the only purpose of which was to switch itself off.

Underlining this playfulness were serious reasons to develop predictive machines: “We hope,” wrote Shannon, “that research in the design of game-playing machines will lead to insights in the manner of operation of the human brain”. Shannon noted at the time, as did Lacan and Guilbaud, that the game of matching pennies had already been used to model human predictive behavior in Von Neumann and Morgenstern’s Theory of Games and Economic Behavior and that the game had been a key figure in Edger Allen Poe’s Purloined Letter. Shannon & Hagelbarger also wanted to develop a machine that could readjust itself and adapt: “Perhaps in an extremely complicated situation it might be easier to design a machine which learns to be efficient than to design an efficient machine as such.”1[1] It was also useful, within the communications industry, to have machines that could execute complex actions with humans and other machines whilst using minimum processing power. In the case of SEER the processing power was minimal and yet it was able to produce complex behaviour in both human and machine, and furthermore, the complexity produced when the intersubjective space between human and machine. The machine had only 16 bits of storage (2 bytes) but was nevertheless able, in a game of long duration, to outguess its human opponent 65%-75% of the time. SEER gave a binary choice between “left” or “right”. In the first move the machine guessed randomly, after which it “learned” from the patterns produced by its opponent. Its choice of left or right would be dependent on the human opponent’s previous choice (its dossier of choices) and on a random choice.

The machine broke the penny-matching model down into eight scenarios, each with a particular probable outcome. For example: if the human player wins twice in a row with the same choice –let’s say “right”–, the human tendency would be to switch on the third move – to “left”–, because to stick with “right” would not be random. Such decisions were recorded as a “1” or “0” in SEER’s 16-bit memory. For each of the eight scenarios the machine recorded the last two only – filling the 16-bit memory. To predict its opponent’s move the machine would check the last two moves taken when the particular scenario in question occurred and choose the same. If the human opponent chose differently it would use a spinning commutator, which gave a random result.2[2] The human was likely to lose against SEER in the majority of cases because it was close to impossible for humans to counterfeit random choice. Shannon, however, notes that he was able to outguess SEER by getting into the “mind” of the machine, mentally emulating the machine’s operation and then doing the opposite. However, because the machine plays randomly, even a perfect human emulator could only ever win 75 % of the time.

In the later stages of the experiment the human factor was eliminated altogether, as Shannon & Hagelbarger had two outguessing machines play each other, with play invigilated by an “umpire” machine.

In March 1953 Claude Shannon wrote a Bell Laboratories memorandum entitled “A Mind-Reading (?) Machine” in which he noted that “[The game of matching pennies/ones and twos had been] discussed from the game theoretical point of view by von Neumann & Morgenstern and from a psychological point of view by Edger Allan Poe in his story The Purloined Letter. Oddly enough, the machine is aimed at Poe’s method rather than von Neumann’s.”3[3] In Poe’s story, the detective, Dupin, discusses the game of odd and even on the basis that people can be predicted even when they try not to be. Von Neumann & Morgenstern’s emphasis was on the role of random choice had on the player of the two-person sum-zero game. Lacan’s seminar and lecture addressed the complexity of both these positions. In Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944) Von Neumann & Morgenstern had proved mathematically that random choice becomes a defensive position if the two protagonists are evenly matched. If they are evenly matched the introduction of randomness will give the player acting randomly advantage. The machine (SEER) can, however, produce a true random result, which a human opponent to the machine can less readily do.

A source of amusement at the Bell Labs for Shannon & Hagelbarger was that the elite scientists who played with SEER understood it as a test of intelligence. It is the unconscious (non-conscious) structure of such a machine that renders it unbeatable. It was Lacan’s task to stress the importance of this to the participants in his second seminar.

We have noted that Lacan’s discourse on cybernetics centred on von Neuman & Morgenstern’s s game theory and that the series of +s , –s , 0s and 1s were, for Lacan, units of probability which establish the syntax within a symbolic system.

From the early 1940s John Von Neuman had been keen to establish a relationship between the way a computer operates and the way the organic neural system operates.1 Von Neuman posited that a form of machine intelligence could be achieved if the machine was built on the principles of McCulloch-Pitts model of neuron activity. McCulloch-Pitts became the bridge between a cybernetic approach (which recognised a relation between the operations of servomechanisms and biological systems) and information theory, (which concentrated on the effectiveness of the message and the operations of “thinking machines”). The bridge between them is negative entropy.

In Warren S. McCulloch’s Machines That Think and Want (1950), McCulloch outlines the precise relation between a rudimentary 16-bit computer (such as SEER) and the human neural system. McCulloch proposes that we think of a neuron as “a telegraphic relay system which, tripped by a signal, emits another signal” this takes a millisecond, and again in line with a single state computer, “its signal is a briefer electrical impulse whose effect depends only on conditions where it ends, not where it begins. One signal or several may trip a relay, and one may prevent another from so doing.” [4] McCulloch invites us to understand such signals as the atoms of a molecular event. “Each goes or does not go” (an all-or-none impulse). It can only signal that it was tripped, and its signal implies that it was tripped. “The signal received is an atomic proposition. It is the least event that can be true or false.”[5] McCulloch next introduces a simple symbolic system to map these “atomic units”. The system is comprised of a series of Xs denoting a specific operation.

.X = A happens (a single neuron has been tripped)

X. = B happens

‘X = both happen

X, = neither happen

X = The signal of a neuron never tripped (contradiction).

The system describes several things.

1) the operations of a 16-bit computer (such as SEER)

2) the activities of neurons as units of probability

3) revealing 1) and 2) as essentially negentropic.

“Every next atomic event, depending on two present atomic events, is shown as a dotted X of which there are 16.” The calculus of propositions in such a scheme is 16. This is essentially the structure of SEER. The operation of each atomic event is linked to probability. If in a particular millisecond we are given ‘X , since its probability is ¼ its amount is 2 units [of information]” Any machine yet built cannot match the number of operations undertaken by the human brain. The Human brain is showered with a superabundance of stimuli which mostly fail to coincide. “Information measures the order of the ensemble in the same sense that entropy measures its chaos. In Wiener’s phrase, information is negative entropy; and our X’s the more the dots the greater the entropy.”

An elaboration of the scheme makes this clearer

X

.X

X.

‘X

X,

.X.

,X.

‘,X’

‘X’,

‘ We reject a great deal more information than we receive; we see an agreement occurs in those instances where dots are absent” In this way information is adjustive and produces a filter with consolidates particular atomic events (‘x or x’ &c)[6]

“Circuits with negative feedback return a system toward an established state which is the end of the operation – its goal. Reflexes left to their own devices are thus homeostatic.” [7]

McCulloch next moves to establish a relation between homeostasis within the body and brain and the governor of the Steam Engine. Just as each receptor within the body serves to return a given perimeter to its established value, so within the brain the impulses through the thalamus to the cortex are inhibited through limits established by negative feedback. The response of the circuits passing through this system “depends on the time the returning meet the incoming signals”.

Some cycles resonate and oscillate, which may tend toward excitability and instability (positive feedback). Others regulate any such excitation, which results in homeostasis (negative feedback). The servomechanism most importantly operates on the information passing through the system regulated by negentropy, which guards against overrun or positive feedback. The starting point of which has been a series of Xs

The key point here, particularly as we go on to discuss Lacan’s Seminar IIin greater detail, is that McCulloch has established an equivalence between the operations of a finite state computer, the operations of a servo mechanism and the operations of the human neural system. Lacan’s seminar was open to discussing the implications of this equivalence.

As was discussed in a previous chapter, McCulloch had very little time for the discipline of psychoanalysis, and after establishing how neural activity (be it man-made or begotten) is organised, next makes a link to purpose.2

McCulloch charts how the cycles which produce homeostasis in an organism also produce what we recognise as psychic activity.

[image of governor]

“[P]urposive acts cease when they reach their ends. Only negative feedback so behaves and only it can set the link of the governor to any purpose. By it we enjoy appetites which, like records that extend memories, pass out of the body through the world and returning stop the initial eddies that sent them forth.” This process of what McCulloch terms “apititation” is manifold and may, like the involuntary actions of swallowing and breathing, be contradictory or “incommensurate”. The outcome of such conflict can be described as choice. ([8] In this way McCulloch links the operations of the governor to the operations of the psyche, suggesting an alternative to Freudian psychoanalysis (in which motivation is regulated by psychic energy). In McCulloch the circuit of “apititation” (desire?) is that of information; which links involuntary actions, such as breathing and swallowing, which are regulated by the same homeostatic circuits.

In a previous chapter we have discussed the implications of the cybernetic discourse for Lacan, particularly in relation Freud’s notion of psychic energy. We have also established how Lacan considered cybernetics to have had a substantial impact on discourse itself.

Indeed, the cybernetic discourse of homeostasis, circuitry and regulative feedback would continue be central to Lacan’s Seminar II as it progressed, as would the particular elements discussed in this and the previous chapters. In his analysis of Edger Allen Poe’s The Tale of the Purloined Letter, and in his lecture on Cybernetics and the Unconscious which concluded Seminar II, Lacan would discuss Von Neumann & Morgenstern's Game Theory and Economic Behaviour; the game of odds & evens (which is discussed in both Poe’s story and in Von Neumann & Morgenstern's book). Lacan would also describe a “second guessing” finite state automata (similar to Shannon & Hagelbarger’s SEER) in order to outline the tendency of symbolic apparatus (be they begotten or man-made) to produce patterns which enter the circuitry of signification.

Lacan’s seminar on the Purloined letter, which takes up part of Seminar II, was a public manifestation of a dialogue that had been going on for some time, principally with the Author of What is Cybernetics? (1954) – who was also the co-organiser of the Paris congresses on cybernetics (1950-1951) – Georges Theodule Guilbaud.

Guilbaud’s “Lectures on the Principal Elements in the Mathematical Theory of Games” had earlier made explicit reference to Edger Allan Poe’s Purloined Letter. In various other texts Guilbaud notes the game of odd & even (ones & twos), mentioned in Poe’s tale as equivalent to Matching Pennies, the game cited for similar analysis by Neumann and Morgenstern in Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944).4[9] In Guilbaud’s lecture “Pilots, Planners, and Gamblers: Toward a Theory of Human Control”, Guilbard posits the idea that the game of Odds & Evens presents the possibility of the mathematicians’ dream – the pure game ((jeu pur). In this lecture Guilbaud also cites an earlier work by Jacques Lacan, Logical Time and the Assertion of Anticipated Certainty, (1945) which discusses Neumann and Morgenstern’s Theory of Games and Economic Behavior no more than a year after its publication. 5F[10] For Lacan the game theory of Neumann and Morgenstern, the communications theory of Shannon and the notion of the (theoretical) universal machine conceived by Turing allowed for a wholly up-to-date conception of the unconscious[11] By 1954, as Lacan opened his seminar, a particular kind of machine had emerged that both illustrated and performed the formation of the subject in exterior relation to the machinery of the game. It was specifically finite state automata such as the SEquence Extrapolating Robot (SEER) that allowed Lacan to claim that “the symbolic world is the world of the machine.” In the case of the tortoise and in the finite state automata, the same relation is established. Both machines – in their encoding and in their production of symbolic material (be they conscious or not) – demand an encounter with an other.

ODD OR EVEN? – LACAN

“...when one illustrates the phenomenon of language with something as formally purified as mathematical symbols - and that is one of the reasons for putting cybernetics on the agenda - when one gives a mathematical notation of the verbum, one demonstrates in the simplest possible way that language exists completely independently of us.” [12]

Jacques Lacan’s Seminar II comes half a decade after French elite intellectuals were introduced to game theory, cybernetics and communication theory.

In Odd or even? Beyond Intersubjectivity, Lacan explains the function of a machine very similar to SEER, Lacan got participants to play odd or even (matching pennies) and to record the results (win or lose) as + or – symbols. [13] The events follow a similar narrative to the one described by playing Shannon & Hagelbarger’s SEER.

Lacan unpacks his argument carefully and is, perhaps uncharacteristically, systematic in developing his argument. Lacan first introduces the game of odd and even as played in Poe’s story; he then outlines how people routinely play the game, “second-guessing” their opponent; he then outlines how a machine, lacking the capacity to “second guess”, might play the game differently. Lacan introduces the notion of randomness and the extreme difficulty the human subject has actually being random – in contrast to the unconscious machine. Lacan also introduces the idea of recording the results as + and – in the following configurations:

++

– –

+ – .

8[14].

Lacan outlines how the game is played between two people and compares it to how a human plays against a “thinking machine”. In a human to human game a single play has no meaning (it makes no difference). There is no surprise if you hold the same (odd or even) as your opponent. In the first play you have a 50% chance of winning, on the second play a 25% by the third play you have a 12.5% of winning. You are soon caught in a play of difference where the odds decrease and the stakes rise with each play. The odds are produced by knowledge of the previous play, by knowing that the opponent knows you are caught in the chain of signification. The play produces a pattern of choices which amounts to a trail of probability, a record or memory of the game (which is why it was important for Lacan that a record of the + and – be kept when participents to the seminar played the game). Lacan points out that even at this early stage we have “left the domain of the real and entered realm of symbolic signification”9. This is defined by the + &– and – &+ which record each move. The fact that the + & – is written brings the player into the realm of probability. For Lacan “the very notion of probability presupposes the introduction of the symbol into the real.” 10 [15] The order of wins and losses only makes sense when they are written down in a sequence, if it is not written down, there is nothing to win; “the pact of the game is essential to the reality of the experience sought after.” 11 [16] In the first few moves of odd and even, Lacan has raised three issues that will become central to our examination of his cybernetic discourse. The first is that the introduction of the symbolic into the domain of the real produces a circuit between signs, things and subjects. Secondly, Lacan stresses the centrality of probability; as the seminar progresses, the “conjectural science” of the 1700s become central to Lacan’s discourse of cybernetics – the period of conjectural science is when probability, which studied ratios of difference, emerged as a discipline. (see chapter eleven). The third issue is that the simple choice establishes a difference which establishes and consolidates order (the negentropic function of making a choice).

Lacan next considers what happens when a human plays the machine. Again the player must make a simple choice (a difference that makes a difference). The player must then inform the machine that they won or lost. Lacan then surmises the interior workings of the machine (sketching a mechanism very similar to SEER) which

a) records the results,

b) reacts to its opponent and

3) periodically randomises its response.

The player does not know the extent of the record kept by the machine or its ability to recall that information. Lacan notes that the machine will win by virtue of the human players exhaustion, as play progresses the human would not be able to calculate the machine’s next move without recourse to (ironically) an adding machine. This summation is similar to the accounts of the operations of SEER.

Lacan next hypothesises that a player might surmise that the machine is an equal match, that the machine is identical to the player. 12[17] If this were the case the player would be the other to the machine. The machine would contain a “psychological profile” of its human opponent and would be capable of second guessing the human player. In such a case “a simple oscillation comes back” ordering the relation between machine and human, and the human player will resort to random choice – in this case the “psychological profile is completely eliminated”.13[18] Whether the machine plays like an idiot or an intelligent human, the human will make the same play. Here Lacan articulates a central premise of von Neumann & Morganstern’s sum-zero two-player game and the mischievous psychology wired into the circuitry of Shannon & Hagelbarger’s SEER.

So, irrespective of whether your opponent is an idiot or a genius, the next stage is to play at random. Lacan recalls a random action reported to Freud, which becomes the point of fixation. A number pulled out of a hat will quickly lead the subject “to that moment when he slept with his little sister, even to the extent that he failed his baccalaureate because that morning he had masturbated”14 [19]Such a realisation will force the subject to understand that there actually is no such thing as chance. Without the subject being conscious of it “the symbols continue to mount one another, to copulate, to proliferate, to fertilise each other, to jump on each other, to tear each other apart”.

Extract a single particle, like a number from a hat, a “chance” particle which makes a screen on which to order memory. Here lies the difference between remembering (a definable property of living substance) and memory (the grouping and succession of symbolically defined events). Memory involves integrations – by which something new in the string of symbols will effect what went before. There is a retroactive effect which is “specific to the structure of symbolic memory, in other words to the function of remembering.”15.[20]

Lacan comes back to the issue that, be it a machine or an idiot or an intelligent opponent, all that is needed for there to be a subject who asks a question is the quod: the demonstration of proof; the signal that the proof has been demonstrated (the + &–). It is on this quod that the interrogation bears.

Lacan prepares his class for the next session (The Purloined Letter), pointing out that, irrespective of the player’s intellectual acumen, after three goes it is best to play like an idiot – because after the third play: “everything loses its signification”.

PURLOINED LETTER – LACAN

At the start of the session on the Purloined Letter Lacan reminds the participants that the introduction of the + – notation system outlines the difference between memory and remembering: the memory is “internal to the symbol” (grouped in succession). Being “internal to the symbol” is stochastic in nature and follows the logic of probability. “The human subject doesn't foment this game, he takes his place in it, and plays the role of the little pluses and minuses in it. He is himself an element in this chain which, as soon as it is unwound, organises itself in accordance with laws. Hence the subject is always on several levels, caught up in crisscrossing networks.”16[21] Lacan invites the members of the seminar to play odds and evens. He sets them a task to play together for the next seminar and assigns the mathematician in the group to define randomness.

In the next session Lacan stresses that in this game, and as a general principle, “the play of the symbol represents and organises, independently of […] a subject”

Lacan gives another account of the story to those assembled (less than half of those attending had read it).

[brief account of poe’s story]

In Poe's Purloined Letter, detective Dupin relates the tale of an eight-year old boy who was adept at the game of odd or even. The rules are simple: guess if your opponent is holding an odd (one) or even (two) pennies in their hand. As we have established, a very similar game was known to Von Neumann & Morgenstern as matching pennies and is discussed in their book on game theory, Game Theory and Economic Behaviour, it is a good example of a “zero-sum two-person” game. This is ostensibly the same game that the machine SEER was designed to play. We also know that if contestants in odd and even are evenly matched, it makes sense for a player to play randomly because chance gives the advantage when two players are evenly matched. 17[22] But it only makes sense to employ chance if you know the field, if a record of the game has cycled through the system, if you know the record of the game [and you know your opponent knows it too]. This foreknowledge of the opponent’s knowledge structures the game of ones and twos, as it does the narrative of the Purloined Letter.18 Lacan and the members of the seminar played the game and made a record. The record, a series of + and –produce a syntax of order that governs each successive move . This establishes autonomy of self-organization of the symbolic order. 19[23] "The symbol [–] produces by itself, its necessitates, its structures, its organizations"20 [24] Within this the subject will always find its place [25]

In such a circumstance, players become place holders in a game which promises a particular outcome. On a level of basic structure, irrespective of who wins, there will be a winner, and irrespective of who plays there will be players; the structure of the game produces a loser and a winner (subjects), this much is established at the very beginning of the game. In this way the game, the purloined letter and SEER are machines of subjectivity. This ordering operates on the level of syntax, insofar as it established the conditions in which a more sophisticated system of signification can be established.

Lacan moves on to examine the plot of the Purloined Letter in such terms, concentrating not the psychological element – which demanded the investigator to put himself in the place of the opponent (the emphasis that Shannon also took in his memo about SEER) – but rather the degree to which the game itself structures the symbolic. The content of the actual letter is not relevant. The possible effect of the content, and the fact that the content is the key to power and control, provides the main emphasis. A message that is not sent can still send a message. If I fail to send tax returns to the tax office they will receive the message that the message has not been sent – and there will be consequences (as Bateson was fond of pointing out). This is at the base of negentropic economies: if it takes little energy to send a message, it takes no energy to not to send a message, and yet not sending a message registers a difference that makes a difference. Similarly, for the protagonists in the tale of the purloined letter, who through their actions and non-actions send messages unconsciously, the letter becomes the machine for action that allows the various individuals in the story to find their place, they are caught in a play of difference. In the manner of the game of odds and evens, those with knowledge of the letter’s contents and whereabouts have a different stake in the game than those who are ignorant of it. In this way the letter, as it passes through the circuit, is the inanimate agent of subjectivity; and in this sense “the letter always reaches its destination” 21[26] and affects the subjects in the circuit irrespective of their knowledge of it. 22[27]

The subjects in the circuit are subjects in a discourse over which they have no control. The story introduces three subject positions that are mirrored as the story progresses. There is a compromising letter to the queen which the minister purloins and replaces with a substitute; the queen sees this, the king does not see this; the queen takes advantage of the kings ignorance, as does the minister, Dupin recovers the letter by using the strategy the minister had used against the queen. The pattern repeats itself, passing through the circuitry of the various protagonists: king, queen. minister, police, minister, detective, the pattern dictates that the subjects in the pattern MUST repeat.

Now, how does this symbolic order relate to the world of the machine? The symbolic order encodes the real as number, or as Lacan would have it, "it ties the real to the sequence" which allows the integration within the circuit. A signifying mark (position of the letter) reveals the syntax, engenders the subject position that in turn engenders / generates subjectivity (it gives a place to) and allows movement within the circuit23 and as in the changing places of the 0 and 1 in SEER).24 [28]

Lacan further examines the point that the space of the letter is the space of difference: the letter cannot be purloined because a letter does not have a stable state of belonging, a proper place to be. Does its place of belonging rest with the person who sent it or with the recipient? The letter is “speech which flies”, a “letter is a fly sheet” whereas “speech remains” even when no one remembers it any more. It is not part of remembering and yet it is part of memory because the succession of a, b, y and s will still be determined under the same law (the stochastic symbolic order). In the order of probability it is not a specific thing that has its proper place, rather it is the thing which finds its place. Lacan will return to language’s tendency to “fly” and the compulsion for things to find their “proper place” his lecture on cybernetics (see chapter *)

Speech remains but the letter wanders by itself because it cannot rest with the sender or the receiver; its place is within the contingent space of the circuit. The letter, in its circularity, is a character, it becomes for the other characters within the circuitry of the story synonymous with “the original, radical, subject” In each case “the letter is the unconscious”. 25[29]

At the end of the seminar, in “questions to the teacher” Lacan returns to the circuitry of the Purloined Letter in relation to the Oedipus myth. It transpires that the tale of the purloined letter sits in isomorphic relation to the story of Oedipus. The letter is the radical character which wanders by itself. Oedipus’ tale is the function of the oracle, his fate was foretold, which gives the ground to the fate of Oedipus. In this sense Oedipus precedes himself, his story goes before him, he is the head and tail of a message that runs in a circuit, and Oedipus is, by necessity, ignorant of the discourse which inscribes him as a subject. Indeed, Oedipus’ destiny depends on the veiling of the discourse, “which is the reality of which he is ignorant.” Here Lacan describes the unconscious function of language as that machine which inscribes the subject which sits in homologic relation not only to the circuitry of the Purloined Letter but also to Grey Walter’s Tortoise, Ross Ashby’s Homeostat and Shannon & Hagelbarger’s SEquence Extrapolating Robot (SEER). In his profound ignorance Oedipus sends clear messages. This discourse, this circuit, which is invisible to the subject, is the cybernetic unconscious.

- ↑ Poundstone,William. How to Predict the Unpredictable , Oneworld 2014.

- ↑ Poundstone,William. How to Predict the Unpredictable , Oneworld 2014. In an earlier version of the machine Hagalbarger had included a nuanced feature which calculated the percentages of outcomes of the eight scenarios. This proved to be unnecessarily complicated and was simplified to a zero-sum machine in later versions.

- ↑ Poundstone,William. How to Predict the Unpredictable , Oneworld 2014

- ↑ Warren S. McCulloch, Embodiments of Mind, Machines That Think and Want 307

- ↑ Warren S. McCulloch, Embodiments of Mind, Machines That Think and Want 308

- ↑ Warren S. McCulloch, Embodiments of Mind, Machines That Think and Want 309

- ↑ Warren S. McCulloch, Embodiments of Mind, Machines That Think and Want 309

- ↑ Warren S. McCulloch, Embodiments of Mind, Machines That Think and Want 310

- ↑ Liu, Lydia H. The Freudian Robot: Digital Media and the Future of the Unconscious. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011. p.301

- ↑ Liu, L. H. The Freudian Robot: Digital Media and the Future of the Unconscious. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011.301

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 19541955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. (Seminar on the Purloined Letter) p?

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954 1955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. (Seminar on the Purloined Letter)

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954 1955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. (Seminar on the Purloined Letter) p*

- ↑ This form of notation is also used by the (theoretical) Turing Machine (1936)

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954 1955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988.

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954 1955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. (Odd or Even) p.182)

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 19541955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. (Odd or Even) p.184

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 19541955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. (Odd or Even) p.184

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 19541955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. (Odd or Even) p.184

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 19541955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. (Odd or Even) p.185

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 19541955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988. p.197

- ↑ Neumann, John V., and Oskar Morgenstern. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (Commemorative Edition). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. See chapter: Zero-sum Two-person Game Theory, p 148

- ↑ Johnston, John. The Allure of Machinic Life: Cybernetics, Artificial Life, and the New AI. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008. P.77

- ↑ Seminar II 782 redo)

- ↑ Seminar II 787redo).

- ↑ Lacan, Jacques, and Jacques-Alain Miller. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 19541955. Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1988

- ↑ Paul C. Grimstad: Algorithm: Genre: Linguisterie: "Creative Distortion" in "Count Zero" and "Nova Express" Author(s)::Journal of Modern Literature, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Summer, 2004), pp. 82-92 On the matter of “finding a place”, Paul C.Grimstad notes that Lacan’s reworking of Sussure’s S/S into S/s renders S/s an algorithm . As an algorithm S/s cycles through the machine (the symbolic circuit). If the task of the imaginary is to maintain the illusion of self (ego) S/s, as an algorithm, represents the element which finds a place within the symbolic for the real. In this sense, S/s processes = the function of the symbolic is to process (this point is also made by La Pont)

- ↑ Lacan patches into the architecture of "thinking machines" by passing through his own triad of Real (transmission), Symbolic (storage) and Imaginary (processing) See Kittler and Fuller and Lovink

- ↑ Cite http://lacan.com/seminars1.htm