THE GOVERNOR: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{:Samuel Butler – The Vapour Engine}} | {{:Samuel Butler – The Vapour Engine}} | ||

{{:Samuel Butler – Vibrations}} | |||

[[Kenneth Craik – A (Proto) Cybernetic Explanation]] | [[Kenneth Craik – A (Proto) Cybernetic Explanation]] | ||

Revision as of 13:50, 4 August 2020

Samuel Butler: “We shall never get straight till we leave off trying to separate mind and matter. Mind is not a thing or, if it be, we know nothing about it; it is a function of matter. Matter is not a thing or, if it be, we know nothing about it; it is a function of mind.” [1]

Gregory Bateson: Up until Lamarck mind was an explanation of the biological world. But, Hey presto, the question now arose: is the biological world the explanation of mind?" [2]

In this chapter I will discuss the work of Samuel Butler, who made a series of claims in relation to consciousness and purpose, and in relation to machine life and organic life which were avant cybernetics.[3]

In Evolution Old and New (1879) Butler articulated a dialectical relationship between the discourse of the machine and the discourse of evolution. These claims would later be reformulated in more precisely cybernetic terms by Gregory Bateson, Norbert Wiener, Kenneth Craik, Warren McCulloch, and others. Furthermore, even before the notion of genetics had been adequately theorised, Butler conceived that adaptation within nature was caused by the accumulation, and transmission, through natural selection, of any variation that happened to be favourable.[4]

Samuel Butler had been a strong adherent of Darwinian evolutionary theory since 1859, when he first encountered Charles Darwin’s The Origin of The Species. The two men conducted a correspondence as Butler published a series of texts which took the theory of natural selection as their starting premise. These publications included Darwin Among the Machines (1863) which speculated on the conditions necessary for a machine to evolve in the manner of an organism (a theme revisited in Butler's novel Erewhon a decade later).

In 1863 Samuel Butler sent a letter to the editor of The Press, Christchurch, New Zealand which was published under the heading, Darwin Among the Machines (and signed under the pseudonym Cellarius).[5] in which he speculated that via natural selection, machines might evolve consciousness.

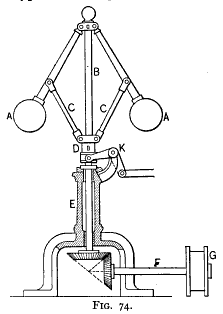

“We refer to the question: What sort of creature man’s next successor in the supremacy of the earth is likely to be.” It will be, answered Butler the machines man designs, regulated by man-made contrivances which give them a “self-regulating, self-acting power”. Machines with the ability to self-regulate were already amongst us, these were the “vapor engines”, or steam engines, regulated by a governor.[6]

The satirical thread running through Darwin Among the Machines is that humans should resist the rise of the machines despite the fact that these advanced machines will be in every respect better than humans. They will possess no human (all too human) imperfections such as avarice, ambition, jealousy, or impure desire. Butler muses on ways in which the general lot of humans might actually improve, as they assume their role as the domesticated life-stock of superior mechanical life-forms. As slaves who attend to their needs, humans will be treated well. The master-machines will treat humans in the same way any enlightened farmer would recognise the value of good husbandry. As machines grow in complexity and subtlety, demanding more from human lives, there will even come a point when they will self-produce. “There is nothing that our infatuated race would like more than to see the fertile union between two steam engines” writes Butler, isolating the death-wish at the heart of this very human fantasy.

Here, Butler registers a vital shift in the discourse of the machine. It is at the point that the “vapour engine” arrives on the scene that an equivalence between organic life and machines gains a new plausibility. In 1858 the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallis, whilst recovering from a delirious bout of malaria in Ternate Indonisia, had noted that natural selection (which Wallis had conceived independently of Charles Darwin) was akin to the self-regulation of a steam engine. “The action of this principle [natural selection] is exactly like that of the centrifugal governor of the steam engine,” wrote Wallis “which checks and corrects any irregularities almost before they become evident; and in like manner no unbalanced deficiency in the animal kingdom can ever reach any conspicuous magnitude, because it would make itself felt at the very first step, by rendering existence difficult and extinction almost sure soon to follow.” [7] Wallis’ description of a self-regulating feedback loop represents another significant shift toward the discourse of the machine – which Butler will be swift to pick up on in his novel Erewhon (1872). This new relation to the machine recognises that the essential boundaries between organism and machine, organism and environment, organ and tool, conscious purpose and involuntary action are increasingly hard to maintain. As far as Darwin Among the Machines is concerned, the fictional author of Butler’s letter advocates a revolution. Humans must rebel and destroy the machines before we sleepwalk into dependency and, as the master-slave dialectic is complete, reach a point of “absolute acquiescence in our bondage”.

EREWHON

The possibility of mechanical evolution is developed further in Butler’s novel Erewhon: Over the Ridge (1872). The novel takes a similar form to More's Utopia (1516), Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), Voltaire’s Candide (1759) or William Morris’ News From Nowhere (1908), wherein the hero-traveller (in this case Higgs) encounters an unfamiliar world in which a series of topsy-turvy values are demonstrated. In Erewhon sickness is regarded as a crime and punished with imprisonment. By contrast, crime is regarded as an illness and those afflicted are pitied and rehabilitated. The young are educated in Colleges of Unreason, where they are taught an obsolete “hypothetical” language (a parody of the English private school system). The people of Erewhon are all uncommonly beautiful, due to the fact (I assume) that a process of eugenic selection has taken place over generations – as the sick are destined to perish in prison. The society of Erewhon maintains a surprising equilibrium, despite the violation of the central conventional values of Higgs' society.

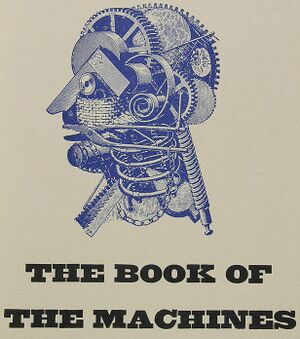

The citizens of Erewhon, fearing the rapid advance of innovation – and, it seems, following the same reasoning as the author of Darwin Among the Machines – had stopped all technological development some centuries before our hero’s arrival. In a revolt against technology the people “wrecked all the more complicated machines, and burned all treatises on mechanics, and all engineers’ workshops”. The Erewhonians retained a museum of wrecked machines, which serves as a warning against the hubris of technological progress. They also left a text, The Book of the Machines, which gives an account of the reasoning behind the ban. In Erewhon the text is recounted by Higgs. The Book of the Machines presents a treatise on consciousness – built and begotten – which binds together the discourse of the machine and discourse of evolution.

Butler comes straight to the extreme implications introduced by Wallis’ in 1858: “But who can say that the vapour engine is not a type of consciousness?” asks the author of The Book of the Machines “Where does consciousness begin and where end? Who can draw the line? Is not everything interwoven with everything?”

The author goes on to challenge a series of divisions between organism, environment, machine, and consciousness which are problematised by the arrival of the “self-regulating” machine controlled by negative feedback – the vapour engine. The adaptations performed by the steam engine are not designed, in the sense that a consciousness outside of itself dictates its adaptation. Any alterations and adaptations are dictated within itself.

EVOLUTION OLD AND NEW

In Evolution Old and New (1879) Butler’s argument extends the dialectical turn established in Erewhon. Butler points out that the modern discourse of the machine is produced within the discourse of evolutionary theory. This is because central to the discourse of evolution is the issue of design. The issue of design (purposeful or otherwise) was not adequately accounted for in the dominant Darwinian evolutionary theory of Butler’s time – where the agent of change is simply chance.

For Butler, when one addresses the idea of evolution the issue of purposeful design inevitably becomes central. Whether you take the position that nature is designed or that it is ruled by chance, the metaphor of the machine is inevitably played against that of the organism. Even theists who would argue against natural selection would characterise the supreme deity as a supreme designer (as had been the position of William Paley’s Natural Theology (1809). Butler’s Evolution Old and New examines this dialectic in some detail.

CYBERNETICS-WIENER-DARWIN-SMITH-MARX

To briefly recap, for Butler, in Evolution Old and New the discourse of purpose is entwined with the discourse of evolution because the discourse of evolution inevitably invites an analogy between the human designer and the divine architect. One side of the argument allows that the complexity evident in nature is proof of a higher purposeful entity. The counter to this position is that change and adaptation are the product of chance. Butler opposes both these positions. For Butler, the evolutionary argument produces a distinction between the “mechanical” and the “vitalistic”. Butler goes to great lengths to point out that this distinction is fundamentally false. Butler argues against an interpretation of Charles Darwin’s natural selection which over-emphasises the role of chance in adaptation, in favour of a model of adaptation closer to Charles’ father Erasmus Darwin, and the elder Darwin’s near-contemporary Jean-Baptiste Lamarck.

Butler argues that adaptation is a form of non-conscious learning, an embodiment of a series of differences within the organism over generations. In challenging the emphasis of chance in evolution, and in affirming a high degree of complexity and difference, Butler attempts to articulate a phenomenon yet to be named: negative entropy.

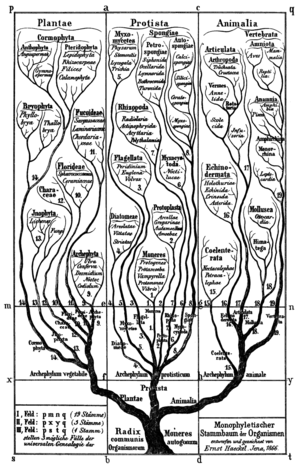

In Evolution Old and New Butler poses the question: if adaptation is a matter of chance, given the order and complexity within nature, would it not be fair to suspect that the dice has been loaded in some way? To refute such a position, which would invite a form of “vitalism”, Butler introduces the notion of teleology (purpose) and invokes the theories of German evolutionist Ernst Haeckel (if only in order to dismantle them at a later point in the argument).

Butler, outlining Haeckle’s premise, identifies two distinct approaches “a causal or mechanical” approach and a “teleological or vitalistic” approach. Up until the advent of evolutionary theory the purposeful and vitalistic was the auspices of the biological world. Nature and all the organisms within it were driven by purpose and ruled by design. It is plain therefore that there must either be a designer who "becomes an organism, designs a plan, &c.," […] “or that there can be no designer at all and hence no design”.[8] Butler takes exception to this latter position that “purpose in nature” does not exist (which essentially was Haeckle’s), but he also rejects the necessity for a divine hand – which must itself be the product of purpose and design and must resemble the organisms which it designs – which sets up an eternal regression which will never reach first cause.

So, I need to clarify what Butler means by purpose.

Purpose, for Butler, relates to adaptation – a thing fulfils a purpose when it is adapted to a particular end. But there are different types of adaptation. Butler takes as his examples a corkscrew, which is man-made and adapted to a particular purpose. He puts this against a pair of human lungs, which have adapted through natural selection. For Butler “the very essence of the ‘Natural Selection’ theory, is that the variations shall have been mainly accidental and without design of any sort, but that the adaptations of structure to need shall have come about by the accumulation, through natural selection, of any variation that happened to be favourable.”

Here Butler establishes a definition of purpose which accords with the definition developed in Wiener et al’s Behaviour, Purpose and Teleology (1943) (see chapter one), and it is built on exactly the same technical standard: that a new definition of purpose is established through the operations of a servo-machine, in which negative feedback is the regulator. It is with this technical standard that Butler (and later Bateson) will apply to the regulative principles of evolutionary adaptation.

In Butler, a structure is established through an accumulation which favours ordered variation. With this Butler sets out the aim of Evolution Old and New, to reintroduce the notion of purpose into evolutionary processes without necessitating a deity as its grand designer or leaving the issue to arbitrary chance. To establish a ground for such a discussion, Butler introduces a hypothesis very close to negative entropy: that it is the accumulation and reiteration of information within an organism which favours variation.

To establish his opposition to conscious design, Butler quotes extensively from William Paley’s Natural Theology, or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity (1802), which, in order to prove conscious design within nature, describes the anatomy of the human body in mechanical terms.[9] The bones and joints are like delicately engineered hinges and pivots; the eye is far more sophisticated than any telescope; the most rudimentary human organs far more complex than any clock. Paley goes on to describe the exquisite complexity of the human circulatory and nervous system, in all its forensic detail, as proof of conscious purpose. Paley, in his day, was attempting to refute the theories of Erasmus Darwin by arguing – as people would of his son Charles’ work – that the sheer complexity and order of the natural organism is evidence of a purposeful designer.

Butler takes up this idea and develops the argument to a significant degree, returning repeatedly to the machine juxtaposed with the organism, which had been a central figure in Butler’s argumentation since the days of Darwin Among the Machines. One could, for instance, present a human foot in its complexity and detail alongside a man-made foot composed of ingenious mechanical parts:

“We not only feel that there is a wider difference between the ability, time, and care which have been lavished on the real foot and upon the model, than there is between the skill and the time taken to produce Westminster Abbey, and that bestowed upon a gingerbread cake stuck with sugar plums so as to represent it, but also that these two objects must have been manufactured on different principles.”[10]

Butler describes these different principles by pointing out that a purposeful designer, when designing a machine or building for a specific function, would not go through redundant generations of design. The designer would not first need to erect a hut before designing a cathedral, for instance, and yet nature seems to do precisely that. Closer to the cybernetic era, Kenneth Craik will describe this ability of the human mind to model as a way in which human beings are able to conserve energy through the storage and transmission of information, Craik’s The Nature of Explanation (1943) describes such negentropic reactions as “down-hill reactions” which “saves time, expense and even life”[11] (I will come back to Craik’s ideas later).

In contrast to the purposeful, down-hill, design of human beings, Butler continues “One would say that nature feels her way, and only reaches the goal after many times missing the path.” To ease Butler’s argument into the cybernetic era I will describe the “path” as a threshold or perimeter and the “many times” as the many iterations which eventually find their “goal”. The structure of such a “path” and the presence of the “goal” are both immanent within the system.

Back in Evolution Old and New, Butler is in a heated imaginary debate with the theist, Paley. Butler demands that Paley produce his designer of nature and asks what form such an entity could take. In Butler’s imagination Paley retorts with an equally vehement demand of habeas corpus: “where is your designer of man?” Butler’s answer draws on the distinctly cybernetic interpretation of purpose we outline above. For Butler it is man himself who is the artificer, “best fitted for the task by his antecedents”. This is not a particular man or a man from any given generation but rather man (humanity) over the entirety of its existence. Butler describes the organism of the human adapting in co-extensive relation with it's environment as follows:

“[…] we say that the designer of all organisms is so incorporate with the organisms themselves so lives, moves, and has its being in those organisms, and is so one with them they in it, and it in them that it is more consistent with reason and the common use of words to see the designer of each living form in the living form itself, than to look for its designer in some other place or person.”[12]

Here Butler sketches a picture of the process of biological adaptation which will be familiar to readers of the cybernetician Gregory Bateson. In Butler and Bateson’s vision of adaptation the distinction between environment and organism (man + environment) is arbitrary, there is no precise point at which the organism (human) is wholly distinct from the environment. This is also the vision handed down to Butler by Dr. Erasmus Darwin, Comte de Buffon (Georges-Louis Leclerc), and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, which does not deny purpose, or demand a designing hand outside of the organism itself:

“It is that the design which has designed organisms, has resided within, and been embodied in, the world of organisms themselves.” […] “being that power in [organisms] whereby they have learnt to fashion themselves, each one according to its ideas of its own convenience, and to make itself not only a microcosm, or little world, but a little unwritten history of the universe from its own point of view into the bargain?”[13]

Butler lacks the word "genetics" – which will be introduced into the English vocabulary by William Bateson, (Gregory’s father, see Vibrations). Whilst Butler’s proposition resolves the distinction between purposeful design and chance, it raises a question which was at the heart of the evolutionary debate: what agent, or “power”, facilitates such changes? How could Butler articulate the function of homeostasis within a discourse in which the gene (a unit of heredity and also a unit of probability) and feedback are absent?

LIFE AND HABIT

Whilst discussing an earlier work by Butler, Life and Habit (1877), I would like to bring Gregory Bateson’s observations about Butler’s work front and centre into the conversation. I do this for two reasons: firstly I want to outline the similarity between the two theorists’ views, even across a century; and secondly I want to outline how Bateson, who is unambiguously cybernetic in his world-view, uses Butler’s work as an epistemological instrument, to argue a particular narrative of knowledge production. I hope this dramatic shift between the two is not too abrupt and that the reader will not get seasick as we move from the “proto-cybernetics” of Samuel Butler’s writing in the 1900s, to the “cybernetics-proper” of Gregory Bateson in the following century.

In Life and Habit (1877), Butler describes a process of evolution in which ingrained activities are reinforced on a local level, even after such a time that they are redundant. For example, we are oblivious to the function of our internal organs and give them no more thought than we would to

“Julius Caesar in the month of July” […] “we have made the one kind [of organ] so often that we can no longer follow the processes whereby we make them, while the others [exterior organs] are new things which we must make introspectively or not at all, and which are not yet so incorporate with our vitality as that we should think they grow instead of being manufactured.”[14]

Again, Butler draws our attention to the false dichotomy between the mechanical and the organic and at the same time to the equally false dichotomy between the interior and the exterior, between organism and environment (these binary distinctions become problematic once we understand the whole is regulated by an information flow within a system). Such distinctions are reinforced, however, in order to maintain order on a local level. This is resonant of Gregory Bateson’s application of the notion of levels of abstraction, and the debt is acknowledged in Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind. On the matter of levels of the mind, notes Bateson: “Samuel Butler's insistence that the better an organism ‘knows’ something, the less conscious it becomes of its knowledge, i.e. there is a process whereby knowledge (or "habit" — whether of action, perception, or thought) sinks to deeper and deeper levels of the mind.”[15]

Habit, in Butler, might be understood as a form of unconscious code or embedded knowledge which serves to conserve energy and transmit information within the organism. Habit traverses both unconscious and conscious action. Gregory Bateson states:

“Samuel Butler was perhaps first to point out that that which we know best is that of which we are least conscious, i.e., that the process of habit formation is a sinking of knowledge down to less conscious and more archaic levels. The unconscious contains not only the painful matters which consciousness prefers to not inspect, but also many matters which are so familiar that we do not need to inspect them. Habit, therefore, is a major economy of conscious thought.”[16]

Bateson recognises habit as an expression of negentropy, but for Butler, as with Bateson, these habits might prove to be counterproductive. Butler’s evolutionary theory and theory of habit can be understood as antecedent to Gregory Bateson’s ecological theories (we will see later in Floop, that Gregory’s biologist father William Bateson, who coined the term “genetics’, was also influenced by Butler’s ideas). Butler’s conception of habit reappears in Gregory Bateson’s essays from the late 1960s and early 1970s, in which the different levels of (un)consciousness are understood as variables which allow flexibility or re-enforce inflexibility within a system (as we will see later). [17]

It is on the level of genetic theory, which Butler was in great difficulty of articulating adequately in his day, that Bateson outlines Butler’s position, which is that nature relied on cunning rather than luck (chance), and explains how more recent knowledge of genetics had resolved the deficiency in Butler’s theory.[18] Bateson is also able to resolve Butler’s unfinished business through an understanding of the role of negentropy in evolutionary development, at the heart of which is the organisation of information.

Bateson: “The notion is that random changes occur, in the brain or else-where, and that the results of such random change are selected for survival by processes of reinforcement and extinction. In basic theory, creative thought has come to resemble the evolutionary process in its fundamentally stochastic nature.”[19]

In which case, Bateson maintains a little later “Samuel Butler's hunch that something like ‘habit’ might be crucial in evolution was perhaps not too wide of the mark.” [20]

CONCLUDING

In the pages of Erewhon Butler makes his most visionary claim in the starkest terms, looking toward Grey Walter’s cybernetic tortoise, toward Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics and toward Bateson's ecology of mind. The narrator of the Book of the Machines writes:

“Let anyone examine the wonderful self-regulating and self-adjusting contrivances which are now incorporated with the vapour-engine, let him watch the way in which it supplies itself with oil; in which it indicates its wants to those who tend it; in which, by the governor, it regulates its application of its own strength;[…]” but “man” must "be awakened to a sense of his situation, and of the doom which he is preparing for himself.” [21]

Butler’s relation to the machine and organism is similar to the double-sided relation between organism and machine outlined in Wiener’s Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and Machine (1948) and The Human Use of Human Beings (1950). What matters for Butler is not the distinction between the machine or organism per se but rather the machine or organism’s relation to purpose. Long before Wiener Butler identified the coming discourse as the discourse of the machine. Long before Jacques Lacan would outline the dialectic of the machine (in his 1954-55 Seminar II) – Butler would describe his own dialectic between the machine and organism, a dialectic which was produced within the discourse of evolution. The knowledge of a progressive ‘design’ or apparent purpose within nature first produces an uneasy equivalence between the designs of man and the designs of nature – the contradictions of both are exposed, brought into the open. This dichotomy is transcended by a new understanding of purpose, and Butler proposes an unconscious purpose which is itself embodied in the act of adaptation within evolution. Here Butler outlines a dialectical relation which Wiener, Bateson, and Lacan would echo in the twentieth century.

{{#set:Machine=Vapour Engine}}

Samuel Butler: “All thinking is of disturbance, dynamical, a state of unrest tending towards equilibrium.”[22]

THREE VIEWS OF EVOLUTION – SAMUEL BUTLER, WILLIAM BATESON, HENRI BERGSON

In Vibrations (1885), Samuel Butler reflects that he had made three contributions to the theory of evolution:

- In Life and Habit (1877) Butler had established the relation between heredity and memory.

- In Evolution Old and New (1879) he had reintroduced teleology into organic life

- In Unconscious Memory (1880) he had suggested an explanation of the physics of memory and made a connection between consciousness and evolution.[23]

Butler's theory of vibrations, which is outlined in Notebooks (1885), represents an extension of his evolutionary scheme. Charles Darwin had proposed natural selection but was unable to explain how units of inheritance are transmitted. Darwin put forward the theory of pangenesis, which proposed that genetic characteristics are passed on through generations by particles of inheritance called gemmules.[24] Darwin suggested that an organism’s environment could cause modifications to the gemmules which are passed through the genitals of the parent to the next generation (this was a modification of Lamark's theory and an adaptation of a similar theory by Herbert Spencer)[25].

The theory had some credibility in the 19th century but continued to lose ground as the examination of evolutionary evidence became more granular. In 1900 Darwin's theory became obsolete following the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel’s (1822-1884) work. In the middle of the nineteenth century, Mendel had studied the reproductive behaviour of plants over generations and identified units of heredity (which he called “factors”). William Bateson (1861-1926) devised the term genetics to describe these units of heredity, which led to the eventual discovery of the encoded script within all living organisms, known as chromosomes.

But I'm getting a little ahead of myself. Back in 1885 Butler is struggling with the problem of how traits of heredity are transferred from one organism to another. He intuits that it has something to do with information, but what could the medium of transmission be?

Butler hypothesises that there is a universal substance which runs through everything and which, vibrating at different frequencies, takes on different forms. In Butler’s words: “[…] the characteristics of the vibrations going on within it at any given time will determine whether it will appear to us as (say) hydrogen, or sodium, or chicken doing this, or chicken doing the other.”[26] The universal substance has some relation to the notion of Luminiferous aether, the substance that was believed to act as a medium through which light waves passed [27] and which will later, in the popular imagination become the medium for any ineffable thing (including radio waves).

Butler then, imagined the universal substance to be in a state of vibration. This vibration constitutes matter itself and the frequencies of the vibrations constitutes particular kinds of matter (it is an immediate medium). The universal substance modulates difference within the material world and because it communicates differences, the universal substance is both “mental and physical". In Butler the vibrations constitute a network of communication, patterns which establish the conditions for reproduction and adaptation: “May we imagine” writes Butler “that some vibrations vibrate with a rhythm which has a tendency to recur like the figures in a recurring decimal, and that here we have the origin of the reproductive system?”[28]

VIBRATIONS AND THE UNIVERSAL SUBSTANCE – BUTLER AND THE BATESONS

The polymath Gregory Bateson (William Bateson's son) in his collection of texts Steps to an Ecology of Mind, makes a connection between his father and Samuel Butler which identifies modulations of communication in nature as registers of difference:

“My father was a geneticist, and he used to say, ‘It's all vibrations,’ and to illustrate this he would point out that the striping of the common zebra is an octave higher than that of Grevy's zebra. While it is true that in this particular case the ‘frequency’ is doubled, I don't think that it is entirely a matter of vibrations as he endeavoured to explain it. Rather, he was trying to say that it is all a matter of the sort of modifications which could be expected among systems whose determinants are not a matter of physics in the crude sense, but a matter of messages and modulated systems of messages. It is worth noting, too, that perhaps organic forms are beautiful to us and the systematic biologist can find aesthetic satisfaction in the differences between related organisms simply because the differences are due to modulations of communication, while we ourselves are both organisms who communicate and whose forms are determined by constellations of genetic messages.”[29]

A decade later, Gregory Bateson acknowledges again that he and his father had been following the same course in relation to biological and mental variation, which both operate under the order of difference:

“[…] if we separate off, for the sake of enquiry, the world of mental process from the world of cause and matter, what will the world of mental process look like? And [the elder Bateson] would have called it, I think, the laws of biological variation, and I would be willing to accept that title for what I am doing, including, perhaps, both biological and mental variation, lest we ever forget that thinking is mental variation.”

Gregory Bateson identified a continuity of enquiry between Butler, his father and himself which circled around the problematic of systemic order, and which is resolved by a cybernetic reading of homeostasis and negative entropy (the communication of variation): “We (a thin line of thinkers from Lamark, to Fechner, to Samuel Butler, to William Bateson) knew that mind must in some way enter into the larger scheme of explanation. We knew that ultimately the theory of evolution must become identical with a resolution of the body/mind problem.”[30]

WILLIAM BATESON – EVOLUTION, INFORMATION, ENERGY – PROBLEMS OF GENETICS

In 1906 Gregory Bateson’s father, William Bateson wrote:

“We commonly think of animals and plants as matter, but they are really systems through which matter is continually passing. The orderly relations of their parts are as much under geometrical control as the concentric waves spreading from a splash in a pool. If we could in any real way identify or analyse the causation of growth, biology would become a branch of physics.”[31]

William Bateson established the modern science of genetics by reviving the theories of Gregor Mendel (1822-1884)[32] Mendel had identified recessive and dominant traits in successive generations by crossing varieties of pisum sutivum (peas). Mendel was able to ascertain the ratio at which these dominant and recessive traits are inherited, which established hybridisation - evolution as organised statistically. Mendel conducted experiments which carefully selected particular strains for hybridisation and allowed other specimens to cross-fertilise naturally and established statistical results for each type of group.[33] Working with Mendel's extensive empirical research and thorough methodology, William Bateson was able to argue specific diversity on a more solid basis than had previously been possible.[34] This granulated approach was closer to Lamark than the orthodox Darwinian approach (which favoured chance as the agent of adaptation, or germ theories similar to those proposed by Darwin and Herbert Spencer).[35] The Bateson-Mendel emphasis allowed for genetic change within a biological system to be transmitted on the level of information, as opposed to the conversion of energy within a closed entropic system. The distinct difference deserves note: dynamic equilibrium requires an exchange of energy whereas homeostasis requires an exchange of information.[36]

From the start of his career Gregory Bateson carried his father’s approach into the heart of his own work, allowing the accommodation of key ideas in relation to pattern, symmetry, and repetition which derived from his father’s work on genetics.[37]

In later life Gregory Bateson would make the relation of evolutionary adaptation and information explicit: “My father coined that word [“genetics”] in 1908 – it was still necessary to call the elements of Mendelian heredity ‘factors.’ Nobody could then see or would risk the notion that these must be ideas or chunks of information or command.”[38] In Gregory Bateson’s early work as a biologist he had researched the emergent symmetry of pigeons and fish “Even then, I think that the fact of communication and the fact of regularity, symmetry, etc., in anatomy, were going hand in hand.” but it was only twenty years later, when he started his cybernetic research that Bateson was able to recognise the homology between different systems, and that the “regularity in the anatomy of flowering plants was comparable to the regularity which linguists found in language.” Bateson, when referring to his father’s work, often outlines ways in which the elder Bateson anticipated homeostasis and negative entropy and intuited evolution and mind as different levels of abstraction within a larger evolutionary system.

In Problems of Genetics (1913) William Bateson argues that specific diversity (genetic mutation) allows for variation within a given species. For William Bateson, specific variation is evident in the fossil records of organisms from vertebrates to bacteria: “In all these groups there are many species quite definite and unmistakable, and others practically indefinite.”[39] It is evident that the evolutionary line is not as simple to read as might be first supposed. As evidence continued to amass after Darwin posited the theory of natural selection, and as this data was analysed and studied, it became increasingly apparent (to William Bateson at least) that variation is neither “evenly distributed” within nature or “arbitrary” and that variation occurs for a number of reasons, which all relate to specific variation.

When this variability is broken down it can be attributed to a number of factors: In part a result of hybridisation; in part a consequence of the persistence of hybrids by parthenogenetic reproduction – in which reproduction occurs without fertilisation (this is common in bees, ants, plants, and reptiles); it might be in part due to polymorphism – in which case alternative phenotypes are produced within the same group; or variability may be due to the continued presence of individuals representing various combinations of Mendelian allelomorphs – which indicate alternative forms of the same genes (here a gene is understood as a unit of heredity).[40]

It is also the case that species “gradually derived from a common progenitor”[41] continue to thrive in the same environment, they do not render each other extinct, in which case it is a question of difference rather than fitness. Furthermore, a variation is sometimes so common that it loses all definition; take British Noctuid Moths, “Many are so variable that, in the common phrase, ‘scarcely two can be found alike’ ’’.[42] Variation, therefore, takes place in a multiplicity of local forms for a number of different reasons.

But, having said that, an alligator cannot give birth to a photocopier.

If the differences are multifarious, what keeps differences from being totally arbitrary? What accounts for the fixity within some species and great variety in others? To beg the same question in cybernetic terms, what restraints and thresholds are in place?

In order to address that question William Bateson, like Butler had done a generation before him, must come up against the problematic of a concept which did not yet exist: negative entropy. The very fecundity of the natural world and the very complexity of variation within it argued against the entropic model of heat death, whereby heterogeneity within a system decreases, and also argued against the entropic logic of “the survival of the fittest”.[43] William Bateson, in Problems of Genetics(1913), allows that natural selection and specific diversity both play their part, but the challenge to the orthodoxy of natural selection, which in the time of William Bateson was meeting increasing number of anomalies, was genetic code’s flexibility, which allowed for both fixity and variation. The elder Bateson held that “the phenomena of variation and stability must be an index of the internal constitution of organisms, and not mere consequences of their relations to the outer world.” The notion of an index which informs structure is a good deal more precise than Samuel Butler, who searched similar territory by supposing that every organism contains: “a little unwritten history of the universe from its own point of view” but William Bateson, to use "stochastic" in its etymological sense, was still unable to hit his target in the centre.[44]

William Bateson: “As soon as it is realised how largely the phenomena of variation and stability must be an index of the internal constitution of organisms, and not mere consequences of their relations to the outer world, such phenomena acquire a new and more profound significance.”[45]

The notion that the transforms which occur in evolution are executed through the transmission of code gained support over time.

By 1943 Erwin Schrödinger‘s What Is Life? lectures suggested that chromosomes contain the coded script of living organisms, a decade before being given empirical credence by Watson and Crick. In the same series of lectures Schrödinger made the relation between genetic code and negative entropy explicit. [46]

ENTROPY, CREATIVE EVOLUTION, AND HENRI BERGSON

This brief overview of William Bateson’s understanding of specific diversity makes it clear that, like Butler before him, William Bateson is unable to make a specific relation between negative entropy, information, and evolution. But a full theorisation of the role of negative entropy is still some distance away. This is why, at this stage in the Fabulous Loop de Loop, we encounter a number of thinkers who repeatedly stumble over the issue of entropy.

To clarify this issue, I will compare William Bateson’s approach to the entropic conundrum with that of another influential voice in the evolutionary discourse at the beginning of the 20th century, Henri Bergson.

William Bateson had held that animals and plants are "systems through which matter is continually passing". This notion of the continuity of existence seems, on the face of it, close to Henri Bergson's Creative Evolution[47] but there are significant differences of emphasis and substance which I want to investigate further. These differences centre on how energy and information is distributed within a system.

Bergson faces the same dilemma as his contemporaries, how does one account for adaptation and the growth in complexity of organisms without violating the second law of thermodynamics? For Bergson entropy is at the very centre of adaptation, it is that force which exercises upon matter an increased degradation and disorder. For Bergson, entropic forces make matter "unmake itself".

In order to square the circle between a universe which is unmaking itself and a universe which is generative, Bergson makes a distinction between entropic matter and a vitalistic consciousness. But this is not a hard and fast dualism, Bergson understands consciousness and matter to be two divergent entities which are preserved within the continuity of duration (Bergson describes a co-dependent duality, a productive equilibrium).

Bergson made a thumbnail sketch of his theory in a 1911 lecture thus:

“If, as I have tried to show in a previous work (Creative Evolution), matter is the inverse of consciousness, if consciousness is action unceasingly creating and enriching itself, whilst matter is action continually unmaking itself or using itself up, then neither matter nor consciousness can be explained apart from one another. […] I see in the whole evolution of life on our planet a crossing of matter by a creative consciousness, and effort to set free, by force of ingenuity and invention, something which in the animal still remains imprisoned and is only finally released when we reach man.”[48]

Bergson’s creative evolution is very energetic. For Bergson life is separated into two distinct halves (“two Kingdoms”)[49]:

- Vegetable life which stores solar energy in the form of potential, stored energy (which Bergson calls “explosives")

- Animals who take energy from the plants (or from other animals who have exploited plant energy). Between the vegetable and the animal: “The one became more preoccupied with the fabrication of explosives, the other with their explosion.”[50]

For Bergson, consciousness is characterised by action: “To execute a movement [of an animal], the imprisoned energy is liberated. All that is required is, as it were, to press a button, touch a hair-trigger, apply a spark: the explosion occurs, and the movement in the chosen direction is accomplished.”[51]

I note here that Bergson describes each “explosion” as a “choice” (a selection from different possible actions). Choice is selective, it affords survivability, because simply put, the organism that makes the “correct” choice survives.

“But life as a whole, whether we envisage it at the start or at the end of its evolution, is a double labour of slow accumulation and sudden discharge.”[52] Matter, whether animate (plants) or inanimate (coal and other stores of potential energy) “hold it available at need as kinetic energy.”[53]

Bergson thinks in equally thermodynamic terms about what he calls “genetic energy” which is

“[...] expended only at certain instants, for just enough time to give the requisite impulsion to the embryonic life, and being recouped as soon as possible in new sexual elements, in which, again, it bides its time. Regarded from this point of view, life is like a current passing from germ to germ through the medium of a developed organism. It is as if the organism itself were only an excrescence, a bud caused to sprout by the former germ endeavoring to continue itself in a new germ. The essential thing is the continuous progress indefinitely pursued, an invisible progress, on which each visible organism rides during the short interval of time given it to live.”[54]

For Bergson the three disciplines of anatomy, embryology, and palaeontology seem to confirm the theory of evolution, that living beings must be adapted to the conditions of the environment: “Yet this necessity would seem to explain the arrest of life in various definite forms, rather than the movement which carries the organization ever higher.”[55]

William Bateson, Samuel Butler and Lamarck would at this point argue for specific diversity as an explanation for greater diversity and complexity, but Bergson takes a route which is more in line with proponents of orthogenesis (progressive evolution).[56]

Bergson: […] “why, then, does life which has succeeded in adapting itself go on complicating itself, and complicating itself more and more dangerously?” Here Bergson identifies an impulse which drives every organism to take “greater and greater risks towards its goal of an ever higher and higher efficiency.”[57] Bergson describes a struggle in which different evolutionary lines, compelled by this impulse, assume different forms.

Where Butler and William Bateson describe an evolution where consciousness is co-extensive with the system of which it is a part, Bergson, by contrast, outlines a dynamic dialectic in which consciousness drives the engine of change. For Bergson, matter is the medium of life, the carrier of consciousness from one state to another.

Bergson: “Now, the more we fix our attention on this continuity of life, the more we see that organic evolution resembles the evolution of a consciousness, in which the past presses against the present and causes the upspringing of a new form of consciousness, incommensurable with its antecedents.”[58]

In relation to the issue of entropy, Bergson is moving in the opposite direction to Butler and William Bateson, whose concepts have a closer relation to homeostasis and cybernetics. In the cybernetic view of adaptation, order is consolidated within the organism in incremental stages so that non-conscious actions can, ultimately, evolve into reflexive action (steps in an ecology of mind). The cybernetic world view does not need to presuppose a consciousness that acts on entropic matter in order to give it vitality. If order and disorder within a homeostatic system are intrinsic to that system, it is an unnecessary complication to add consciousness as a corrective to entropy. It is clear that Bergson’s Creative Evolution opposes the development of the cybernetic evolutionism which Samuel Butler and William Bateson were working towards. Butler and Bateson both opposed a distinction between mind and matter by recognising that the line between matter and consciousness are arbitrary. For Bergson human consciousness is the crowning achievement[59], again, this is at odds with the post-humanistic position of cybernetics, where the bloated intelligence of humans can be seen as the harbinger of ecological peril.

In the preceding chapters, I have described how Samuel Butler, William Bateson, and Henri Bergson struggle with the nineteenth century energy crisis, as they try to square the circle of evolution and human consciousness. I've also made clear that Gregory Bateson sees the resolution of that crisis in cybernetics – which allows for “homeostasis” as a precise expression of “equilibrium” in evolution. Butler and the elder Bateson agree with Gregory Bateson that the evolution of organisms and the evolution of consciousness are realised by incremental factors which undergo a process of selection. They also understand order as internal to the system. Henri Bergson, by contrast, sees consciousness as a force exterior to matter. Bergson’s “mind energy” passess through matter to bring it to higher forms of perfection. The zenith of this process – which has most successfully exploited the potential energy stored in pants and other organisms – is human consciousness. Bergson’s creative evolution is a highly thermodynamic system, by contrast to Butler, William Bateson and Gregory Bateson, whose system is homeostatic.

I will return to Bergson’s Creative Evolution in the final chapter of The Fabulous Loop de Loop, because even in the ecological landscape of 1960s counterculture, Bergson’s entropic-vitalistic model of mind and ecology were prevalent (as were other transformative ecological theories such as the theory of the Noosphere). For now, it is sufficient to say that the understanding of negative entropy as the unifying principle was far from universally recognised. The problem of entropy will continue to be a stone in the shoe as we hobble into the 20th century. I will make clear in the next chapter that Kenneth Craik came closer to resolving the problem of energetics at the heart of adaptation, as he engaged with a thematic which is by now familiar: the relation of the machine to the organism, or the relation of design to purpose, which is tied in a knot that the new conception of negative entropy will attempt to untie.

Kenneth Craik – A (Proto) Cybernetic Explanation

Gregory Bateson – From Schizmogenesis to Feedback

- ↑ S. Butler, Notebooks (1885)

- ↑ G. Bateson, STEM 434

- ↑ Specifically; S. Butler: Darwin Among the Machines (1863); Evolution Old and New, Or the Theories of Buffon, Dr. Erasmus Darwin and Lamarck, as Compared With That of Charles Darwin (1879); Erewhon (1872) and Butler's Notebooks (1885)

- ↑ Samuel Butler, Evolution Old and New, Or the Theories of Buffon, Dr. Erasmus Darwin and Lamarck, as Compared With That of Charles Darwin (1879)

- ↑ S. Butler, Darwin Among the Machines, The Press, 13 June 1863, Christchurch, New Zealand,

- ↑ S. Butler, Darwin Among the Machines, The Press, 13 June 1863, Christchurch, New Zealand.

- ↑ Alfred Russell Wallis: On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely From the Original Type (S43: 1858) http://people.wku.edu/charles.smith/wallace/S043.htm

- ↑ S. Butler EO&N

- ↑ William Paley, Natural Theology, or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity (1802)

- ↑ S. Butler EO&N 5

- ↑ Edward Craik The Nature of Explanation (1943) Cambridge

- ↑ Butler EO&N 30

- ↑ S.Butler EOaN 31-32

- ↑ S. Butler EOaN 157

- ↑ StEM 151

- ↑ StEM 151

- ↑ StEM287

- ↑ Bateson StEM 260

- ↑ StEM 260

- ↑ StEM 263

- ↑ Samuel Butler, Erewhon p.220

- ↑ Excerpt From: Samuel Butler. “The Note-Books of Samuel Butler”. Apple Books. p155

- ↑ Samuel Butler, Notebooks (1885)

- ↑ Charles Darwin The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication 1868

- ↑ Herbert Spencer, Principles of Biology 1867

- ↑ Butler, Notebooks, V: Vibrations ,1885, p.66

- ↑ Huygens, Christiaan, Treatise On Light (1678)

- ↑ Samuel Butler, The Universal Substance, in Notebooks chapter V p. 67

- ↑ Bateson(StEM 237) Gregory Bateson: The Group Dynamics of Schizophrenia In STEM 233- Here Bateson is citing: Beatrice C. Bateson, William Bateson, Naturalist, Cambridge

- ↑ Bateson

- ↑ William Bateson, "Gamete and Zygote," in William Bateson, F.R.S.: Naturalist, His Essays and Addresses Together with a Short Account of His Life, Caroline Beatrice Bateson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1928)

- ↑ after whom William named his son, Gregory.

- ↑ Mendel's published work (1866) does not give a precise name to these generational traits which were christened 'genes' by William Bateson.

- ↑ William. Bateson, Mendel’s Principles of Heredity, a Defence; with translation of Mendel’s original Papers on Hybridisation; Cambridge University Press 1902 , p 8 | William Bateson:“These experiments of Mendel's were carried out on a large scale, his account of them is excellent and complete, and the principles which he was able to deduce from them will certainly play a conspicuous part in all future discussions of evolutionary problems.”

- ↑ Allowing for adaptation. The dispute between theory of Gregor Mendel and William Bateson and Darwinian natural selection persisted through to the 1970s, at which time the seeming contradiction was reconciled in evolutionary genetics (Lipsit)

- ↑ (the energy transference – equilibrium – model as opposed to the information transference – homeostasis– model).

- ↑ Peter Harries-Jones, A recursive Vision. Ecological Understanding and Gregory Bateson(2002), p19

- ↑ Bateson Sacred Unity 185 (1976)

- ↑ William Bateson. “Problems of Genetics.” iBooks. (13)

- ↑ William Bateson. “Problems of Genetics.” iBooks. (24)

- ↑ William Bateson. “Problems of Genetics.” iBooks

- ↑ William Bateson. “Problems of Genetics.” iBooks

- ↑ A phrase coined by Herbert Spencer in Principles of Biology (1864)

- ↑ The term Stochastic derives from a series of arrows fired at a target. After the arbitrary action of firing the pattern is revealed on the surface of the target (see Bateson Glossary)

- ↑ William Bateson. “Problems of Genetics.” iBooks.

- ↑ Erwin Schrödinger What is life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell. lectures delivered under the auspices of the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies at Trinity College, Dublin, in February 1943. In chapter five, Schrödinger states:"[The living organism] feeds upon negative entropy', attracting, as it were, a stream of negative entropy upon itself, to compensate the entropy increase it produces by living and thus to maintain itself on a stationary and fairly low entropy level."

- ↑ CREATIVE EVOLUTION BY HENRI BERGSON, AUTHORIZED TRANSLATION BY ARTHUR MITCHELL, Ph.D., NEW YORK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY 1911,

- ↑ Henri Bergson, Mind-Energy: Lectures and Essays, Translated by H. Wildon Carr, 1920 [1975] p.23

- ↑ Bergson, Life and Consciousness, p19

- ↑ Bergson, Life and Consciousness, in Mind-energy (1911), p19

- ↑ Henri Bergson, Life and Consciousness, in Mind-energy (1911) p19

- ↑ Henri Bergson, Life and Consciousness, in Mind-energy (1911) p19 Note: General Semantics follows a similar energetic model: plants take solar energy, which is converted into kinetic energy which is imbibed by animals (affording animals the capacity to be “space-binding”); In Alfred Korzybski’s General Semantics the introduction of language into human society allows humans to become “time binding”, see Why "The Mp is not the Territory"

- ↑ Henri Beragson, Life and Consciousness, in Mind-energy (1911) p19

- ↑ Henri Bergson Creative Evolution, 1911 p.27

- ↑ Henri Bergson, Life and Consciousness, in Mind-energy (1911) p24

- ↑ the term "orthogenesis" was introduced by Wilhelm Haacke in 1893 and popularized by Theodor Eimer in 1898.

- ↑ Henri Bergson, Life and Consciousness, in Mind-energy (1911) p24

- ↑ Henri Bergson Creative Evolution, 1911 p27

- ↑ "[the evolutionary process] has not found [higher intelligence] with instinct, and it has not obtained it on the side of intelligence except by a sudden leap from the animal to man. So that, in the last analysis, man might be considered the reason for the existence of the entire organization of life on our planet." Bergson, Creative Evolution p185