Double Bind's Double life

THE DOUBLE-LIFE OF THE DOUBLE-BIND

Although Gregory Bateson would continue to be influential in the fields of psychoanalysis and psychiatry – particular as one of the main inspiration for R.D. Laing’s “anti-psychiatry” movement in the 1960s – Bateson, had always had an ambiguous relationship with psychoanalysis and psychiatry.

He left the field in 1961 to pursue research into octopus communication (Bateson held that octopi are capable of communicating abstractly). Following this, in 1962, Bateson joined John C. Lilly’s dolphin communication centre in the Virgin Islands.[1] Double-bind theory continued to be applied in practice as a diagnostic tool and continued to be applied within family-group therapy.

In 1977, returning to the subject of the double-bind for the major psychiatric conference, Beyond the Double Bind [2] Bateson expressed regret that the double-bind had been taken so literally and was frustrated by the oversimplistic applications afforded to the double-bind theory. He pointed out: “Double bind communication […] was a class of behavior not behavior itself and therefore was not quantifiable.” […] "You cannot count the number of double binds in a sample of behavior, just as you could not count the number of jokes in a comedian’s spiel or the number of bats in an inkblot." [3]

For Bateson the double-bind addressed epistemological questions which centred on the relationship between the name and that which is named; these elements are organised within a recursive structure, the double-bind is only useful insofar as it allows one to recognise that all communication is structured in this way.

Bateson: “The matrix, after all, is an epistemology, and specifically it is a recursive epistemology; at the same time, it is an epistemology of recursiveness, an epistemology of how things look, how we are to understand them if they are recursive, returning all the time to bite their own tails and control their own beginnings.” [4]

In cyberneticists feedback creates a homeostatic system, the particular outcomes of that system are not determined. Bateson’s approach to therapy reflected this point, each session would be defined by the particular context, allowing for a performative response to particular circumstances. By 1977 Bateson was repelled by the idea that the double-bind could be a therapy which promised quantifiable results, at the Beyond the Double-bind conference he stated: “ "I'm not very happy at feeling myself the father of the unsaid statement that 'double bind is a theory of therapy.' I do not think it is or was." [5]

Despite Bateson’s protestations, throughout the 1960s the double-bind found its practitioners as a theory and as a therapy. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, video increasingly became as the mediator within individual and group sessions and Bateson’s ideas remained central. Bateson's influence on the counterculture continued to grow, as a presence in Radical Software (as a media-ecologist) and as a key inspiration for Stewart Brand's Co-evolutionary Quarterly (1975).

CYBER-NARCOTICS

They are playing a game

They are playing at not playing a game. If I show them I see they are I

shall break the rules and they will punish me.

I must play their game of not seeing I see the game.

R.D Laing Knots I (1970)[6]

A brief recap; By the mid 1960s Bateson’s influence could be seen on a number of fronts

1) in the field of therapy (an emphasis on group therapy and the double-bind)

2) in the field of aesthetics (an emphasis on self-reflexive, context specific forms of art)

3) within the counterculture (a cybernetic epistemology and [media] ecology).

These influences are at times indirect and at other times explicit. All three strands converged in the pages of Radical Software, in which the tendency to understand video as a medium of self-knowledge, and knowledge of context, crossed into the counterculture with mercurial ease.

It was in the pages of radical Software that video therapists Harry Wilmer and Milton Berger, artists Paul Ryan and Frank Gillette and Bateson himself unified the fields of group therapy, aesthetic expression and (media) ecology . The centrality of video as a technology of self-exploration found close proximity to an understanding of LSD as a technology of the self.

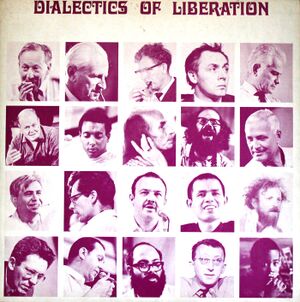

An earlier manifestation of the meeting of cybernetic readings of therapy, aesthetics and context-reflexivity was evident in the Dialectic of Liberation summit in London in 1967. The summit was convened by Dr. R.D. Laing, who in 1965 had established Kingsley Hall, in London. Kingsley Hall became centre of what came to be known as the "anti-psychiatry" movement [7]– which sought to break down the hierarchy between staff and patients and which opposed a “vivisectionist” tendency in mainstream psychiatry, had no locks on the doors, allowed people to come and go at leisure, involved patients in decision making process, did not prescribe (traditional) drugs– and, as such, became the testing ground for alternative ways of living that could extend beyond the walls of the institution.

Laing’s early research included what came to be known as the “rumpus room” experiment at Glasgow Royal Mental Hospital (1955), [8]Here eleven socially isolated chronic schizophrenics and two nursing staff were confined in a room every day over the course of one year. The staff were given no specific instructions about how they should interact or how they should conduct treatment. This experiment was conducted in a context in which the management of the ward was very hierarchical and the contact between patients and staff was minimal. The experiment showed that more intimate contact with the patients meant that behaviour of the patients and the nursing staff changed. “The patients lost many of the features of chronic psychoses; they were less violent to each other and to the staff, they were less dishevelled, and their language ceased to be obscene.” [9]

The modality of the experiment indicated a move toward a more social psychiatry,[10] in which the hierarchies of traditional psychiatric treatment are replaced by more “bottom up” system of day-to-day management. The Glasgow study also revealed tensions between the structures of the institution and the less hierarchical practices modelled in the experiment. It also understood the psychiatric process as adaptive, that all parties within the environment would change through a process. The task of the carer was to enter this process. Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag to form the charity the Philadelphia Association, which opened Kingsley Hall in East London. The aim was to create a model for non-vivisectionist, non-restraining therapies for people seriously affected by schizophrenia.</ref>

Laing had encountered Bateson’s ideas in the late 1950s and was attracted to the idea of the double bind and also to Bateson’s reading of psychosis as an adaptive, progressive process ( a journey). Laing visited Bateson and the Double-bind research group at Palo Alto in 1962.[11] Laing’s interpretation of the double-bind, however, was not reliant on The Theory of Types. Laing would argue that schizophrenia is a response to an impossible situation which arises within the system – the causation does not rest with the mother but is a rather a distorted equilibrium within a given group. The task was to create an environment where a new equilibrium could be established. [??]Here Laing began to use LSD within a group and individual context. As a technology of self, LSD made the user aware of the interconnectedness of things and blurred essential entities – [??!!]

the rest

The ease with which the practice of video therapy shifted from the clinical context into lived cultural experience is a testament to the protean quality of cybernetic discourse. A similar cultural shift occurred when the centre of the "anti-psychiatry" movement Kingsley Hall, in London became a countercultural testing ground which proposed alternative ways of living which could be applied beyond the walls of the institution. It was within this culture, the central figure of which was the psychoanalyst R.D Laing, that counterculture summit, Dialectics of Liberation (1967), which brought together the intellectual leaders of the counterculture (including Gregory Bateson, Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs) was staged [continue]

[...] The tendency to understand video as a medium of self-knowledge, and knowledge of context, crossed into the counterculture automatically.

R.D. Laing's early research in which medical staff worked alongside patients . ... which led to the residential treatment centre Kingsley Hall the "anti-psychiatry" movement...

Knots is curiously "Batsonian" because it deals poetically with the double-bind (without explicit reference to Whitehead or Russell)...

- ↑ With a grant from the National Science Foundation Bateson studied the coding of analogic–nonverbal–signals in octopi. In 1962 Bateson took up a research position at John C. Lilly’s dolphin communication centre in the Virgin Islands. .See Lipsit p233

- ↑ Cited in Lipset: Beyond the Double-bind, New York City, which was sponsored by the South Beach Psychiatric Center, of Staten Island. Those attending included Gregory Bateson, Milton M. Berger, M.D, John Weakland, Murray Bowen, M.D., and Carl A. Whitaker, M.D., Albert E. Schefflin, M.D., and Lyman C. Wynn, M.D. Lipset p. p.294

- ↑ Cited in Lipset: Gregory Bateson: "The birth of a matrix or double bind and epistemology, " in Beyond the Double Bind,p. 41.

- ↑ Cited in Lipset: Gregory Bateson: "The birth of a matrix or double bind and epistemology, " in Beyond the Double Bind, p. 41.

- ↑ Cited in Lipset: J. Haley, "Ideas which handicap therapists," in Beyond the Double Bind, pp. 65-80.

- ↑ R.D Lang Knots p.1 Penguin 1971

- ↑ A. Pickering points out in the Cybernetic Brain p 438: “The term “antipsychiatry” seems to have been put into circulation by Laing’s colleague David Cooper in his book Psychiatry and Anti-psychiatry (1967), but Laing never described himself as an “antipsychiatrist.”

- ↑ Cameron, J. L., R. D. Laing, and A. McGhie (1955) “Patient and Nurse: Effects of Environmental Change in the Care of Chronic Schizophrenics,” Lancet, 266 (31 December), 13 84–86.

- ↑ In Pickering: Cameron, J. L., R. D. Laing, and A. McGhie (1955) “Patient and Nurse: Effects of Environmental Change in the Care of Chronic Schizophrenics,” Lancet, 266 (31 December), 13 84–86.

- ↑ see also David Cooper’s experimental psychiatric ward, Villa 21, at Shenley Hospital

- ↑ Lipsett p.238