Steps Towards a (Media) Ecology

FLEXIBILITY–ECOLOGY

Written content coming soon to this page [rough notes below].

Bateson: "Ross Ashby long ago pointed out that no system (neither computer nor organism) can produce anything new unless the system contains some source of the random. In the computer, this will be a random-number generator which will ensure that the "seeking," trial-and-error moves of the machine will ultimately cover all the possibilities of the set to be explored."

Bateson "I am going to build a church some day. It will have a holy of holies and a holy of holies of holies, and in that ultimate box will be a random number table." [1]

Functionally, the behaviour is the brain.

CYBERNETICS–ECOLOGY

In Conscious Purpose versus Nature [2] Bateson outlines a dialectic that is now familiar to us. Bateson notes that the chain of being and the place of the mind within it – as it had been understood in pre-modern and in non-occidental cultures – has suffered a reversal in the modern Western scientific era. In the modern conception the supreme mind (God/ mind of Man) was at the top, enjoying mastery over the creatures below him, from the higher primates to the protozoa bubbling at the bottom. Bateson argues that this conception does not allow for a conception of mind as imminent within a series of co-extensive systems. The publication of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck's evolutionary theory at the beginning of the 19th century – “the first organised transforms theory of evolution”.[3] ushered in a Copernican revolution in the biological field. Philosophie Zoologique (1809) is revolutionary, Bateson contends, because it acknowledged that the order of nature runs in a converse direction, suggesting that mind is indeed emergent and imminent within an ecology 27.Up until Lamarck "mind was an explanation of the biological world. But, Hey presto, the question now arose: is the biological world the explanation of mind?" […] “Some years [after Lamarck], Russel Wallis, in his correspondence to Charles Darwin described the process of natural selection as akin to the regulation of a steam engine by a governor.”)[4] The full implications of Wallis' insight, that such ecological systems are regulated by negative feedback (an observation also made by Samuel Butler, you may remember), lay dormant until after WWII when the revolution in cybernetics and communication theory allowed for a clearer understanding of feedback as a general regulating principle within different scaled ecological systems (from a single cell to a complex environment, such as Spaceship Earth). It also allowed for an understanding of the formation of social relations and individuation of the human psyche as a process of circular causality driven by purpose. If pre-modern societies had an understanding that mind was coextensive within a series of systems this was rediscovered in the post-cybernetic era as "nowadays cybernetics deals with much more complex systems" of human behaviour, human organization, any biological systems which are all self-corrective. Such systems are always conservative of something, the change in the fuel supply effects the motion of the flywheel which is regulated by the governor [5]

This transaction, in relation to any system, might be understood as survival. This tendency of self-correcting systems toward conservatism is now directed to the subject of the human psych. Bateson notes that the difficulty people have in seeing the obvious, or with coping with disturbing information is an artefact of the system. The tendency to reinforce resistance to the obvious or the disturbing is systematic. "This is a system which conserves descriptive statements about the human being, body and soul. For the same is true of the psychology of the individual , where learning occurs, to conserve the opinions and components of the status quo." Society and the ecosystem are systems of the same general kind. In all such systems there is an "uneasy balance of dependency and competition". The components of a system are "segmented" so that change is localised [...] The biological system is driven to reproduce, even if, to state the obvious, overpopulation will result in a strain on the larger system: any "monkeying with the system is likely to disrupt the equilibrium."[6]. It is therefore, "quite a trick" to balance dependency and competition. The system is segmented so that no single part has access to the "total mind" . However, and here Bateson introduces a mysterious (almost mystical element), “there is a " "semipermiable" linkage between consciousness and the remainder of the total mind. A certain limited amount of information about what is happening in this larger part of the mind seems to be relayed to what we may call the screen of consciousness."[7] Because the screen of consciousness is a filtration system it necessarily provides partial information. The whole mind cannot be comprehended in part of that mind, to comprehend the circuitry of the system would require more circuitry which produces an infinitely recursive logic &c. The question now arises, how is this limited selection of information which plays on the screen of consciousness selected and filtered? "I am guided in my perception by purposes." , thought is responsive and immanent "I get a myth about this subject which might be quite correct. I am interested in getting that myth as I talk. It is relevant to my purposes that you hear me."[8]. In this anecdote thought is imminent to purpose. Purpose becomes that which builds subjects and relations to subjects within the system.36 Here subjects and objects are performativly produced within a circuit of communication where competition and dependency are central agents.

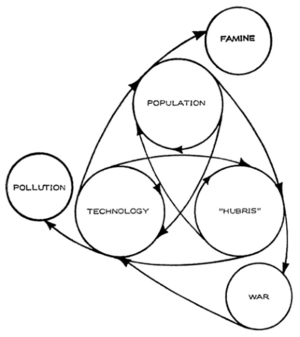

Here Bateson mounts a critique of instrumental reason and the instrumentalization of cybernetic principles: "What happens to the picture of a cybernetic system [...] when that picture is selectively drawn to answer only questions of purpose?"[9]If a system is organized only in terms of purpose it ends up with a “bag of tricks” and no wisdom about the system as a whole, it is organised to arrive at short cuts and quick fixes and to follow the shortest logical path, which may be "dinner; it may be a Beethoven sonata; it may be sex. Above all it may be money and power." [10]. The cause for concern, for Bateson, is the "addition of modern technology to the old system" The system orientated by purpose that consciousness has been using for more than a million years has produced more effective machinery "transportation systems, airplanes, weaponry, medicine, pesticides, and so forth" all produced through the agency of conscious purpose. [11]

Bateson gives an account of conscious purpose which begins in myth. God, in a retelling of the Judo-Christian creation myth, was cast out of the garden on the day that Adam and Eve worked out how to stack one box on top of another in order to get their hands on the apple. At the point at which they realised that A & B can result in C, and were defined by a local aim and purpose they were "cast out of the garden of the concept of their own systemic nature." our consciousness is conditioned to conscious purpose, which is projected onto the screen of our consciousness, such purpose defines the subjects and objects in our world, we produce technologies to meet those purposes, together these things constitute a system which we strive to preserve. We see as through a glass darkly – "Consciousness is blinded to the systematic nature of the individual man" .

Bateson continues to wax biblical: “Lack of systematic wisdom is always punished”.[12] when presenting the cybernetic paradox of consciousness. Bateson continues to call for a revision of "the occidental errors of epistemology"[13], and calls for a humility in the face of nature and in relation to what is known by human beings. Bateson finds useful models in Zen Buddhism, which challenges the sovereignty of the self in relation to natural systems; artistic or aesthetic pursuits which operate under the order of self-reflexive, deutero-learning which alters the register of hierarchical perception; the 'best of religion' serves as a corrective to 'overrun' (positive feedback producing inflexibility and instability within a system).

In this respect the lines of engagement are ostensibly the same as the 1950s, but the stakes at the end of the 1960s, when an ecological disaster seems imminent, are more desperate. Bateson wrote in Radical Software: “... all of the many current threats to man”s survival are traceable to three root causes: a) technological progress b) population increase c) certain errors in the thinking and attitudes of occidental culture. (Our “values” are wrong!)” [14]

The question for Bateson in Restructuring the Ecology of a Great City – written for the office of New York City Mayor John Lindsy and published in the fourth issue of Radical Software –[15] is how to conserve and protect flexibility, which is a measure of the degree of adaptability within the parameters of a given system. Bateson begins the essay by establishing that the exploitation of resources over thousands of years by humans has resulted in a reduction of such flexibility. Human society has been progressively unstable since the introduction of the wheel, metal and script. Indeed the 'pathologies of our time' are an accumulation of a loss of flexibility over a very long period. The ideal city is considered as "a single system or environment with 'high' civilization" in which the flexibility of the civilization and of the environment are equal. The designation 'High' corresponds to the degree of self-knowledge or 'wisdom' of a given society, this is passed down by individuals through institutions (schools, family, church for instance).

Bateson shifts between actual and hypothetical societies; and also actual-hypothetical past and present societies, positing an ideal, ecological society which primarily uses that energy which is available to Spaceship Earth, principally solar, wind, photosynthesis and tidal energy.

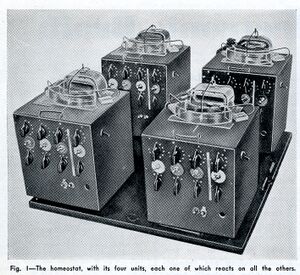

To illustrate the ecological city, and the more general issue of flexibility within a system, Bateson again returns to W. Ross Ashby's Homeostat. In Ashby's model, and Bateson's city, flexibility operates within set parameters, the upper and lower limits of which are strained when tested, resulting in a loss of flexibility throughout that system. Bateson uses the practical (whilst somehow generally hypothetical) example of over-population, which exacts strains on housing, transportation systems and education if tested to the limit, resulting in the city becoming less self-sustainable, less flexible, less ecologically responsive. Bateson advocates the control of ecological resources and seeks to establish authority to preserve the flexibility that does exist (and to allow for instances for it to exist where it currently does not). This, Bateson argues, may justify 'tyrannical' measures.

Bateson advocates a radical humility on the part of humankind, warning that in seeking to have control of a given system one destroys it. The aim is to find one's place within an ecology, which requires a large philosophical AND spiritual leap in the first instance. Bateson has little faith in the current economic and political system – the Viet-Nam war is a folly, the pollution of the environment by corporations is reprehensible, overpopulation and the pollution of ecological systems by DDT indicate that it may be 'too late'. The interventions he makes – speaking on behalf of the Ecology Bill in Hawaii, and the debate on the future city in New York, for example – call for long term changes of individual and collective philosophy, reform where possible (Hawaii) and anti-democratic legislation if necessary (New York). The stakes are high, the very survival of Spaceship Earth.

For Bateson "cybernetics is [...] not simply a change in attitude, but even a change in the understanding of what an attitude is."[16] This introduces the political subject as transcendent: In later writings Bateson would consider that liberal reason requires a self-reflexivity which would allow a profound change in subjectivity. As with Bateson’s consideration of then human psyche or the social unit, there is always a paradox at the centre. For the subject to see themselves beyond the screen of consciousness is not possible, because the the screen of consciousness is the interface between the map of the self and the territory of the self. To know one’s place within system requires a transcendent self-reflexivity. The double bind would be that this transcendent self-reflexivity would be simultaneously a revelation of the self and a negation of the self. To think on the register of the total mind would allow one to see beyond the screen of consciousness and to recognize one’s place in the system. The ecological subject would transcend subjectivity, coming into being at the moment of its dissolution.

Bateson’s cybernetic epistemology necessitates a self-reflective understanding of the individual’s place within a larger system. The (second order) cybernetic approach to negentropy holds that human + environment are part of a single system. Humans are in the position to operate on a “deteuro-level” and order their environment (given that this is to a limited degree given that the universe is, in the long run, entropic). Humans, through making choices, order their environment – an aesthetic position. Humans’ failour to understand their place in the overall system can lead to disastrous environmental consequences, as a sub-system seeks to preserve aspects within itself which run contrary to the order of the greater system – an ecological position.

We also considered that the tendency to self-reflexivity is an artifice of the method described above. In the preceding chapters I have described a number of machines which solicit this self-reflexivity. The last of these machines, the Porta Pak, becomes a technology of self and a technology of collectivity. [17]

- ↑ Stewart Brand recounting an exchange with Bateson's secretary Judy Van Slooten WEC p4901

- ↑ Bateson STEM 433, 1968

- ↑ Bateson, STEM 455

- ↑ STEM 435 Bateson also gives an account of this in Stewart Brand's For God Sake Margaret!, Co-Evolutionary Quarterly 197*

- ↑ StEM 435

- ↑ Bateson, StEM 437

- ↑ Bateson StEM, 438

- ↑ Bateson STEM, 438

- ↑ Bateson STEM,439

- ↑ Bateson STEM,440

- ↑ Bateson StEM,441

- ↑ STEM 441

- ↑ STEM 495

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, Awake, Radical Software No 5 Volume 1, p.33

- ↑ Bateson Restructuring the Ecology of a Great City, Radical Software no 4 1970

- ↑ Bateson STEM, page?

- ↑ It was in the period of Radical Software that art became about self-reflexivity In the first instance it was not intended to be art in any conventional sense (no declarable art products were produced), it was rather an extension and expression of lives lived, an augmentation of potential. In this sense it was a negation of art which has been at the heart of the discourse of art since the birth of modernism, but it nevertheless provided a new condition that art recognised its own self-reflexivity – self-reflexivity was thereafter a condition of artistic production.