From Schizmogenesis to Feedback

Gregory Bateson: "Communication is the substance of common being."

As the son of the founder of modern genetics Gregory Bateson grew up in an environment which was open to advanced ideas in relation to systems and which challenged orthodoxy.[1] and as a student at Cambridge in the 1920s he worked in an environment that encouraged a broad, interdisciplinary approach.[2]Two general questions emerged from Bateson's observations of the Iatmul: how do social systems achieve and maintain balance – why don’t they move to runaway and disorder?

In Bateson's mature thinking schizomogenesis became synonymous with feedback,[3] and was defined as “change with direction”, [4] but in his earlier theorisation of schizomogenesis Bateson encountered a familiar energy crisis: how could unity in division be maintained, what could account for the generative activity of a society systematically divided within itself? [5]

Naven (1936) was Bateson's study of the Iatmul people in New Guinea.[6] The Iatmul,in Bateson's reading, were characterised by a marked contrast between the behaviour and ethos of men and women. This behavior and ethos are mediated by a series of honorific rituals which involve humiliation and transvestitism. In Naven Bateson gives an account of a society regulated by rituals involving extremes of exaggerated boasting and submission. It was through the analysis of this group that Bateson developed the theory of schizmogenesis which he believed could be applied across the social sciences.

The elements are:

a) complimentary schismogenesis - characterised by acquiescence self-deprecating and conciliatory behaviour

In the glossary of Naven: "Complementary. A relationship between two individuals (or betweenmtwo groups) is said to be chiefly complementary if most of the behaviour of the one individual is culturally regarded as of one sort (e.g. assertive) while most of the behaviour of the other, when he replies, is culturally regarded as of a sort complementary to this (e.g. submissive)."[7]

b) symmetrical schismogenesis, characterised by boasting and displays of dominance.

"In the glossary of Naven:Symmetrical. A relationship between two individuals (or two groups)is said to be symmetrical if each responds to the other with the same kind of behaviour, e.g. if each meets the other with assertiveness." [8]]

Schismogenesis, in the context of the Naven rites, concerned how division is generated within a group, but at this stage, schismogenesis could not articulate a satisfactory account of how cohesion is maintained. In Naven Bateson stresses how social life is interactive and intersubjective. One groups actions produce a reaction which may be symmetrical (ritualised boasting, for instance)or complimentary (acquiescence to a hierarchy through submission).

In 1936 Bateson writes:"“I am inclined to see the status quo as a dynamic equilibrium, in which changes are continually taking place. On the one hand, processes of differentiation tending towards increase of the ethological contrast, and on the other, processes which continually counteract this tendency towards differentiation. The processes of differentiation I have referred to as schismogenesis. I would define schismogenesis as a process of differentiation in the norms of individual behaviour resulting from cumulative interaction between individuals." [9]

In Sacred Unity (1977) Bateson writes: “I could not, in 1936 see any real reason why the [Iatmul] culture had survived so long”[10] The question was, how does one account for self-regulation and adaptation within such a fractious social system, without the ordering, adaptation, self-regulation afforded by negative feedback? The observer could note a division, and, against the odds, the observer could note the system achieving equilibrium – but what could account for the system’s order?

In Sacred Unity, (1991 [-1977]) Bateson redefines Schismogenesis in terms closer to Edward Craik and Warren McCulloch, as “a process of interaction whereby directional change occurs in a learning system. If the steps of evolution and /or stochastic learning are random, as has been maintained, why should they sometimes, over long series, occur, recurrently, in the same direction? The answer of course is always in terms of interaction, but in those days we knew approximately nothing about ecology.”[11] Schismogenesis, as a theory of social organisation, shifted definition over the years. In Naven it is defined as a process “of differentiation in the norms of individual behaviour resulting from cumulative interaction between individuals.” Within a society, for instance, there may be assertive individuals and submissive individuals, corrective elements are necessary to stop the society from running to disorder. Within such a society there are anti- and pro- schismogenetic mechanisms– it is through the play of one force against another that balance is maintained.

This is a description of a dynamic system through which an equilibrium is maintained. Such a system is opposed to a homeostatic system in which balance is maintained internally. In Bateson’s writings the shift from schismogenesis from a dynamic (entropic) to a homeostatic (negentropic) system shifts when Bateson adopts cybernetics as a metatheory, in 1942.

In Naven (1936) Bateson proposes schismogenesis as a general theory that can be applied to any social grouping.

Bateson in Naven states:“I think that we should be prepared rather to study schismogenesis from all the points of view —structural, ethological, and sociological— which I have advocated; and in addition to these it is reasonably certain that schismogenesis plays an important part in the moulding of individuals. I am inclined to regard the study of the reactions of individuals to the reactions of other individuals as a useful definition of the whole discipline which is vaguely referred to as Social Psychology. This definition might steer the subject away from mysticism.” [12]

In 1935, the year before the publication of Naven, Bateson had published Culture Contact and Schismogenesis,[13] which outlines the theory without specific reference to the Iatmul. As in Naven, Bateson draws a distinction between symmetrical schismogenesis (characterised by assertive behaviour) and complementary schismogenesis (characterised by submissiveness) and discusses various restraining factors:

“we need a study of the factors which restrain both types of schismogenesis. At the present moment, the nations of Europe are far advanced in symmetrical schismogenesis and are ready to fly at each other's throats; while within each nation are to be observed growing hostilities between the various social strata, symptoms of complementary schismogenesis. Equally, in the countries ruled by new dictatorships we may observe early stages of complementary schismogenesis, the behavior of his associates pushing the dictator into ever greater pride and assertiveness.”

This is typical of Gregory Bateson the synthesist. A principle is applied to a particular instance and then theorised in general terms which encompass the social on a broader scale. An anthropological analysis of a particular group of people becomes a means through which to read, and correct, political division in the 1930s. This instinct to synthesise is a characteristic of his career and cybernetics will provide the consummate vehicle for a meta-theory which spans across previously incommensurate boundaries. After Bateson’s serious engagement with cybernetics the theory of schismogenesis was indeed adapted to accommodate notions of negative entropy and homeostasis. Social division – altered variables within a system – are regulated by homeostasis.

In the epilogue of the 1958 edition of Naven, Bateson gives a reflexive, even self-deprecating, review of the 1936 edition of the book: “The book is clumsy and awkward, in parts almost unreadable", reports Bateson.[14] Bateson’s exposure to cybernetic ideas had, in the intervening time, allowed him to synthesise the information he had gained from his anthropological research with his work in the field of psychiatry during the 1950s (Bateson’s work with Jurgen Ruesch and double bind communication will be discussed in detail later). By 1958, Bateson understood Naven(1936) to be the study of the nature of explanation. “[I]t is an attempt at synthesis, a study of the ways in which data can be fitted together, and the fitting together of data is what I mean by ‘explanation.’”[15] This, from the 1940s on, can be understood as Bateson’s purpose, to bring data from disparate sources together into some form of systematic unity. Bateson recognises a more philosophic purpose: “to learn something about the very nature of explanation, to make clear some part of that most obscure matter—the process of knowing.” ”[16]

Reflecting on Naven, from perspective in 1958, Bateson describes three levels of abstraction– which sketch out the map of the nature of explanation. The first level involves the arrangement of data about the Iatmul. This gives an account of how the Iatmul live. The second level involves discussion of “procedures by which the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle are put together” [17]This generates a lexicon of specialist terminology particular to the discourse in question. The third stage is Bateson’s realisation that the terminology generated to describe the object of research (terms such as ethos, eidos, sociology, economics, cultural structure, social structure) “refer only to scientists' ways of putting the jigsaw puzzle together.” This is not to say that the terminology bears no relation to objective reality, but it does exist at a particular level of abstraction. The terminology (discourse) is itself inevitably part of the system it describes. This self-reflexive epistemology, based, in Bateson's case, on a synthesis of Russell & Whiteheads’ Theory of Types and cybernetics will later be termed “second order cybernetics”.

Still later, in Mind and Nature (1976) Bateson wrote: “[I]n the 1930s I was already familiar with the idea of ‘runaway’ and was already engaged in classifying such phenomena and even speculating about possible combinations of different sorts of runaway. But at that time, I had no idea that there might be circuits of causation which would contain one or more negative links and might therefore be self-corrective”[18]

In Sacred Unity, for instance, schismogenesis is re-visited in terms with which the cybernetician Ross Ashby would be familiar. Bateson states: “(a) that progressive change in whatever direction must of necessity disrupt the status quo; and (b) that a system may contain homeostatic or feedback loops which will limit or re-direct those otherwise disruptive forces.”[19]

In Bateson’s late work, Angels Fear (with Mary Catherine Bateson 1980), schismogenesis is defined simply as “positive feedback”.[21] Schismogenesis therefore moved from a theory which suffered the same energy crisis as many nineteenth-century theories (including Freud’s Dynamic Psychology)(in 1936); to a theory which is resolved by homeostatic theories of the cyberneticians (after 1942). Until the emergence of the theory of feedback and homeostasis, Bateson had been in the same epistemological pickle as Freud.

In 1936 Bateson had high ambitions for the theory and in Naven, he offered that it could be applied across the social sciences.[22] For Bateson, schismogenesis offered an improvement of Freudian methods, which, for Bateson, were over-reliant on the subjective narrative offered by the client. Bateson's accounts of the Iatmul in Naven stress the interdependence of the groups and individuals within that society, in this context the concept of an individuality that transcends the social seems peculiarly occidental. In every aspect of life, in every action and interaction, the Iatmul understand themselves as part of a social matrix. For Bateson, the narrative of subjectivity encouraged in Freudian psychoanalysis obstructed the realization that the patient's condition is co-efficient with interaction with others. In Naven Bateson establishes the ground for his critique of Freud which he would pursue in Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry (1951) in which an application of the theory of schismogenesis serves to oppose the diachronic emphasis of Freudian analysis.

“In Freudian analysis and in the other systems which have grown out of it, there is an emphasis upon the diachronic view of the individual, and to a very great extent cure depends upon inducing the patient to see his life in these terms. He is made to realise that his present misery is an outcome of events which took place long ago, and, accepting this, he may discard his misery as irrelevantly caused. But it should also be possible to make the patient see his reactions to those around him in synchronic terms, so that he would realise and be able to control the schismogenesis between himself and his friends.”[23]

Bateson’s disagreement with Freud rested on two pillars, the first was Freud’s dependence on what Bateson called the “diachronic view of the individual” which, in Bateson’s view, did not allow the individual to sufficiently understand the context which shapes them (The social matrix). Bateson considered Freudian methods to be particularly unhelpful to psychotic and schizophrenic individuals.[24] Bateson's emphasis, based on his work with the Iatmul, was that individual behaviour was a result of cumulative interaction between individuals. This diachronic emphasis, in which the biography of the individual is prioritised, was local to occidental cultures, and should not be universalised.

The second critique of Freudian analysis rested on the very energy crisis which had plagued Bateson’s theorisation of schismogenesis. In the 1930s Bateson had described schismogenesis as a system of “progressive change in dynamic equilibrium”. Freud had also tried to square the energy circle with the Freudian fallacy of Dynamic Psychology. Bateson’s revision of Freud, and of his revision of his own theory of schismogenesis would rely on a new relation between energy and information proposed by cybernetics.

GREGORY BATESON, NEGENTROPY AND FREUD _ the humanistic and the circularistic

Gregory Bateson: “[T]he whole train of thought connected with the Second Law of Thermodynamics (Carnot, 1824; Clausius, 1850; Clerk Maxwell, 1831-1879; Willard Gibbs, 1876; Wiener, Cybernetics, 1948) is ignored by psychiatrists to the extent that while the word ‘energy’ is daily on their lips, the word ‘entropy’ is almost unknown to them.” 21[25]

The war’s end, and into the early 1950s – the period in which Gregory Bateson (with Jurgen Ruesch) wrote Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry – presented a time of upheaval in Bateson’s life. During the war Bateson had worked enthusiastically as an agent of OSS (the precursor to the CIA), where he applied techniques and theories from anthropology to the war effort – including the theory of schismogenesis translated into the practice of disinformation.[26] At war’s end Bateson expressed profound doubts about the use of anthropological methods and data in the furtherance of any state’s interests and would thereafter renounce the instrumentalisation of anthropological techniques. This was in line with the actions of Norbert Wiener, who refused to allow his wartime research material to be used once fascism had been defeated. It was at this time that his book on schismogenesis, at an advanced stage, ground to a halt and his marriage to Margaret Mead ended – although formally divorced in 1950 they were separated from 1946. In 1947 Bateson entered psychotherapy.

It was during this time of re-evaluation that the implications of the new science of cybernetics were recognised, principally through what came to be known as the Macy conferences on cybernetics (1946-1953), which Bateson was instrumental in organising. For Bateson the principles of cybernetics offered a new perspective of his previous work in particular and offered a scientific ground for the human sciences in general.[27]

Late in life, Bateson reflected on the introduction of cybernetics, and the degree to which past theories (his own and others) were re-contextualised: “I was ready then for cybernetics when this epistemology was proposed by Norbert Wiener, Warren McCulloch, and others at the famous Macy Conferences. Because I already had the idea of positive feedback (which I was calling schismogenesis), the ideas of self-regulation and negative feedback fell for me immediately into place. I was off and running with paradoxes of purpose and final cause more than half resolved, and aware that their resolution would require a step beyond the premises within which I was trained.” 23[28]

The cybernetic explanation allowed Bateson to re-think biological and social systems as organized by the feedback of homestatic checks and balances.

Bateson moved to San Francisco in 1948 on the invitation of the Swiss Psychiatrist Jurgen Ruesch where he began research into human communication in psychotherapy at the University of California Medical School (Langley Porter Institute). There Bateson studied the nature of communication between a “tribe of psychiatrists”, taping ethnographic interviews and recording observations of psychiatrists around the Bay Area of San Fransisco. This material formed the basis of Bateson’s analysis of psychiatric epistemology that appears in Communication, The Social Matrix of Psychiatry 24 [29]

In Communication, The Social Matrix of Psychiatry (1951) the authors share the chapters. They were the first to take on the task of relating the current state of psychiatry and psychoanalysis to recent developments in communications theory and cybernetics.[30] For Bateson, as with the other cyberneticians interested in psychology, the introduction of negative entropy into the energy model invited a fundamental re-evaluation of Freud’s dynamic psychology.

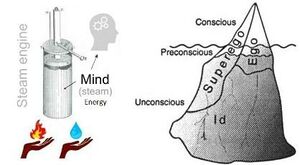

Freud, when developing the system of psychotherapy, built on the dynamic physiology of his former teacher Ernst Brücke (1819 – 1892). This held that every living organisms is an energy system that abides to the principle of the conservation of energy (the first law of thermodynamics). This model holds that the amount of energy within a system remains constant. The energy can be transferred and redirected but it cannot be created or destroyed. From this Freud derived the idea of dynamic psychology, which allowed that, in the manner of kinetic energy, psychic energy can be reorganised within the system but cannot be destroyed. The mind has the ability to redirect and repress psychic energy, diverting it from conscious thought. Classically, the libido, which is the source of sexual energy, becomes redirected, to be manifest in different forms of behaviour. In Freud’s later works a similar dynamic operates as the ego, id and superego struggle for equilibrium. Psychotherapy becomes a technique which rebalances the equilibrium of psychic energy within the system.[31]

For Bateson, in the light of cybernetics it became necessary to challenge the foundational assumptions of classic psychotherapy and psychoanalysis. Bateson identified the tendency to reify abstractions, to focus on an individual's personal history, to privilege the relationship between the client and therapist (as opposed to recognising the “social matrix”); to model reality and pathology in relation to a nineteenth century model of energy conservation which delivers and emphasis on suppression and transference (dynamic psychology).

Freud’s (entropic) theory (central to Beyond the Pleasure Principle) was devised before the notions of negative entropy and homeostasis invited a re-evaluation. This was also the departure point in Lacan’s analysis of cybernetics and Freud in Seminar II (as we will see in chapter *).

As will become clear in the following chapters, although Jacques Lacan and Bateson agreed that consideration of the implications of negative entropy demanded an overhaul of previous ideas relating to psychiatry and psychoanalysis, they differed in approach and emphasis. The key difference was that whilst Lacan seeks to modernize and rehabilitate Freud, to meet the technical standards of the day, Bateson seeks to bury him. Whilst Lacan used developments in cybernetics to mount a dialectical examination of changing discourse, Bateson recognized a change in the epistemological base which fundamentally challenged psychiatric practice as it had been conducted to date. Bateson understood Freud’s world view as wholly predicated on “the errors of epistemology” which more recent non-Freudian models and practices had begun to address.

Although Bateson gives due attention to Freud’s historical significance, in Communication, The Social Matrix of Psychiatry it is clear that developments in communication theory and practice have rendered Freud irrelevant. Bateson identifies four principle characteristics of Freudian psychic energy:

1) “psychic energy is a "substance" (in the strict sense) whose phenomenal aspect is motivation”: drive, purpose, wish, love, hate &c. It is derived from the deep instinctual systems of the personality

2) psychic energy in indestructible, this is in line with the fourth law of thermodynamics

3) it is protean in its transformations; a motivation not acted upon will find a phenomenal expression elsewhere – in sublimation and transference, for instance.

4) Psychic energy is finite, psychic conflict drains the organism of this finite energy.28[32]

All these assumptions are challenged by negative entropy and circular causality. Developments in science in the first half of the twentieth century– principally in the fields of general systems theory, communication theory and the complex of theories known as cybernetics – had transcended the nineteenth-century notions of the physical world which had framed Sigmund Freud’s thought. For Bateson, Freud was “an occidental thinker of the nineteenth century [who] followed the traditional line of Aristotelian-Thomian thinking”29,[33] which in Batesonian terms amounts to an emphatic dismissal.

In chapter nine of Communication, The Social Matrix of Psychiatry, ‘Psychiatric Thinking: An Epistemological Approach’, Bateson makes his most sustained critique on Freud’s system with a reflection on Freud’s approach to the nineteenth-century energy crisis. Bateson opens with the assertion that there needs to be a reexamination of the epistemological premise which underlie the habits of communication within the psychiatric profession. Bateson draws on the interviews and discussions with different psychiatrists and psychoanalysts in the Bay Area he undertook prior to writing Communication, The Social Matrix of Psychiatry, which allow him to examine the assumptions of different “theories of knowledge” practiced within the profession. Some, Bateson observes, think in the Aristotelian mode and others – in line with Norbert Wiener and the founder of general semantics Count Alfred Korzybski – work with a complex mixture of epistemologies taken from 2000 years of occidental thought.

Bateson acknowledges that when speaking it is near-impossible to communicate with epistemological constancy, even in writing it is difficult to not “lapse” into contradiction and vagueness. There is nevertheless a great deal to be learned from these lapses and elisions, and the opinions expressed by Bateson’s subjects present “straws in the wind” which express how the speakers grope for clarity between one scientific pronouncement and another. The two main categories of interviewee are Jungian and Freudian, who are placed in comparative critique against Bateson’s cybernetic epistemology. The argument progresses through different approaches to pathology, through to comparative notions of how a subject relates to notions of “reality”. Bateson argues against a form of solipsism which can result from “relativistic habits of thought” (which is a misalignment of scientific and social discourse), and which allows the subject to regard them self as existing in their own unique “reality” of “private world” 30[34] This can result in either a delusional state or a feeling of total alienation and abstraction from the world. Bateson offers that both these positions are epistemologically flawed. Between the two extremes of solipsism and dissolution of identity “Reality” can be understood in a third way which involved deutero-learning.

The theory of deutero-learning, was first published by Bateson in 1942. Bateson described it as a form of “leaning to learn”, a stage in a hierarchy of learning in which an individual understands context; or more precisely: “learning to deal with and expect a given kind of context for adaptive action”. For Bateson deutero-learning it is the “very stuff of cultural evolution”. Deutero-learning is an understanding of the efficacy of reflexivity, that thought can model and predict future events, in this sense it offers a reflexive methodology in which interaction between individuals is central. Insofar as deutero-learning allows information to be carried forward and consolidated, it might also be understood as an expression of negentropy.

In this discussion about the nature of reality Bateson actually provides a working model of deutero-learning. In this case, the subject recognises its idiosyncratic view of itself and the world is part of “reality”. This gives agency to subjects as they recognise their ability to act adaptively and purposefully in the world. The subject can “correct” for their idiosyncrasies and recognise their own position as one degree more abstract from their immediate perception of it. Bateson labels this the “adjustive” theory of therapy, in which the subject accepts their own special habits of interpretation and performs a “further computational process” which serves to correct habitual errors. 31[35] In recognising the importance of different levels of abstraction, this approach draws on the past work of Stack Sullivan and Korzybski, as well current work of the cyberneticians. Bateson asserts that, if in an open system making a choice brings order, the validity of deutero-propositions is really increased by our acceptance of them. 32[36]

In Communication, The Social Matrix of Psychiatry deutero- learning has particular relevance to how subjecthood is structured. Bateson contrasts deutero-learning with the Pavlovian model. An individual who has learned to avoid punishment will have a different character structure than an individual who has learned through reward; the first will be orientated toward avoidance of punishment, the second will seek reward. In contrast to the perspective of these two individuals, deutero- learning is concerned with context, with a person recognising how a context shapes events and being able to influence context. This is at a markedly different level of abstraction to a Pavlovian response, in which the subject is aware of the imminent reward or punishment, and will act in relation to the anticipated reward or punishment (in Bateson’s terms, proto-learning). The fatalistic Pavlovian subject will behave in a way which reinforces the reality they have experienced, in fact they will seek out instances in which their experience is verified, in this respect their reality is a function of their belief. 33[37] By contrast, at the level of deutero-learning the individual is able to control context, and is also aware of the degree to which they can and cannot control it. The individual operating at the level of deutero-learning is akin to Maxwell’s demon as they order their environment to a far greater degree than an individual who cannot see beyond their actions and the given consequences of those actions. Bateson draws closer to the issue central to Freudian epistemology by drawing on the notions of the “reality principle” and the “pleasure principle” in stating that central to the development of the individual is the postponement and inhibition of discharge – the issue is the distribution, deferral, concentration and quantification of energy – which bring to light the profound difference between world view that emphasises energy and a world view that recognises economies of entropy.34[38]

For Bateson, Freud, in common with other thinkers in the nineteenth century, lacked a physical model with which would allow them to arrive at a precise formulation of the nature of purpose. They were unable to recognise a connection between the self-corrective processes going on within organisms, these were being documented at the time by Claud Bernard and the self-corrective processes at work in the larger environment – including the evolutionary, ecological forms of adaptation and the social phenomena of adaptive behaviour. “Indeed,” claims Bateson “it was the unsolved problems of teleology that determined the great historic gulf between the natural sciences and the sciences of man.” For Bateson, Freud was unable to bridge the gap and borrowed terms from physics to resolve the deficit. “Today there exist many physical and biological models which exhibit self-corrective characteristics—notably the servomechanisms, the ecological systems, and the homeostatic systems—and we know a great deal about the working and the limitations of models of this kind."[39] The foundational change which divides the nineteenth and twentieth century epistemology is an understanding of energy’s relation to order. Bateson stresses again his opposition to a “fatalistic nineteenth century materialism” – in which energy conservation, expenditure and distribution resemble the actions of a billiard ball. This is contrasted with the subject who can, through choice, impose order upon the universe (the Maxwell’s Demon).41 The subject knows that its ability to change its own wishes and purposes, but the subject is an active “participant in [their]own universe”.42[40]

Bateson acknowledges that Freud’s view was never as reductive as the fatalistic materialism of man-as-billiard ball. Freud made the issue more complex by introducing three notions which, although scientifically untenable, allowed for a more complex vision of the human psyche. The Freudian triad was

1) psychic energy, a misnomer which allowed motivation to be justified and articulated;

2) energy transformation which Freud borrowed from physics and allows for the idea that “man can bargain in his energy exchanges”;43[41]

3) a series of entelechies (form-giving causes, such as id, ego and superego) which are introduced and give anthropomorphic agency within the overall theoretical system. Given that it was necessary to humanise the theoretical picture these three speculative figures are understandable in Freud’s context, but in the cybernetic era it is clear that these entelechies cannot be accounted for. 44[42] Bateson rebuilds the Freudian subject in a circuit of communication, whereby, beginning with the “numerous interdependent and self-corrective circuits” it is possible to reconstruct the theory, “starting with entropy considerations.”45[43]

At this point the respective positions of Lacan and Bateson come very close, (as will become clearer in chapter *). Both recognise Freud’s intuition that something more than the entropic model was necessary in understanding the operations of the human psyche. Bateson and Lacan would also agree that Freud was far from recognising a relation between information and negentropy. However, by introducing the triad of psychic energy, energy transformation and the entelechies of id, ego and superego, the function of entropy becomes implicit in Freud.46 It is no longer necessary to establish that “man can bargain in his energy exchanges” when agency is in the hands of the one who plays Maxwell’s demon and makes a decision which, in an open system, brings order. Bateson allows that “Freud's solution was good in the sense that it is today rather easy to translate these entelechies into more modern concepts”. Yet, for Bateson, in the cybernetic era, the entities of ego, id and superego are replaced by other “self-maximating and self-corrective networks.”47[44]

One might ask, given that the foundations of Freud’s theory have been re-evaluated to a point where they are redundant: what is at stake, after one has removed the entelechies of the id, ego and superego; if one rejects the centrality of entropic concepts such as repression, transference and the death instinct; if one rejects that “intrapersonal processes” are the “centre of all events” (favouring instead a “social matrix”)?

Bateson, of course, never proposes a re-construction of Freud’s theories – this was a task taken up by Jacques Lacan, who in his Seminar II (1954-55) will re-cast Freud’s gallery of entelechies in the circuitry of cybernetic theory. (see chapter *). Instead, Bateson dismantles Freudian theory and leaves the pieces to lie where they will. Bateson recognises that the scientistic position of the Freudians, through the use of terms such as "psychic energy", and the entelechies of "id", "ego" and "superego", are legitimate attempts to guard the emerging science of psychiatry and psychoanalysis against

(a) magical thinking and superstition and

(b) a sentimentalised humanism. But, for Bateson, the magical thinking some schools of psychiatry employ (notably the Jungians) and the humanism of others (Sullivanian therapy) are closer to a teleological epistemology than the pseudo-science of Freudianism. In their use of detero forms of thinking (Jung), and in the recognition that all parties with in a community are affected by the social system they are a part of (Sullivan) they display an openness to forms of psychiatric practice which recognise the significance of modern communication theory. It is precisely the closeness of Freudianism to the nineteenth century scientific world view – which misplaces the role of energy and economy in the psychic system – which leaves Freudianism deficient.

Bateson identifies two directions the theory and practice of psychiatry are taking in the 1950s: the humanistic and the circularistic.

Adopting a methodology which will become familiar to readers of Bateson, he takes flagging theories, which are themselves suffering entropy, and resuscitates them with the oxygen of cybernetics and information theory. In later chapters we will discuss how Bateson gave the epistemology of Korzybski’s General Semantics a new vitality when understood through the affordance given by negative feedback; and how the humanism of Sullivan is given a circularistic spin as interpersonal therapy is read in terms of communication theory. These are two examples of the way in which the cybernetic epistemology reordered and restructured existing knowledge, elaborating, re-contextualising and up-dating theories which had been established decades earlier.

- ↑ Lipset, David. Gregory Bateson: The Legacy of a Scientist. Boston: Beacon Press (MA), 1982.

- ↑ Lipset, David. Gregory Bateson: The Legacy of a Scientist. Boston: Beacon Press In his early work as an anthropologist, Naven (1936), Bateson developed the theory of schismogenesis which was concerned with how groups of people are established through division and how such groups organise and maintain their cohesion. Bateson defines schismogenesis in Naven as: "a process of differentiation in the norms of individual behaviour resulting from cumulative interaction between individuals" <refe>Naven p.175

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory, and Mary C. Bateson. Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred. Hampton Press (NJ), 2004. p.12

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Harpercollins, 1996. 89

- ↑ Bateson had high hopes for the theory of schizomogenesis and worked for some years on a book on the subject.Bateson, Gregory. Naven. Cambridge: CUP Archive, n.d.

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, Naven (1936)

- ↑ Naven'Italic text p.308

- ↑ Naven'Italic text p.311

- ↑ Excerpt From: Bateson,Geogory. “Naven”. Apple Books.

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory, and Mary C. Bateson. Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred. Hampton Press (NJ), 2004. P.12

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Harpercollins, 1996.

- ↑ Excerpt From: Bateson, Geogory. Naven. Apple Books.

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. "Culture Contact and Schismogenesis." Man 35 (1935), p.178

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, Naven Epilogue to (second) 1958 edition p.281

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, Naven Epilogue to (second) 1958 edition p.281

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, Naven Epilogue to 1958 (second) edition p.281

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, Naven Epilogue to 1958 (second) edition, p.282

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity. Hampton Press (NJ), 2002. p.105

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Harpercollins, 1996. P.112

- ↑ In their encounter with occidental culture the Iatmul are faced with a dilemma of self-preservation: “either the inner man must be sacrificed or the outer behaviour will court destruction” There is a battle around whose self will be destroyed “that which survives will be a different self”,[Bateson, Gregory. Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Harpercollins, 1996. P.113] because a new relation has been introduced adaptation to the disruption is necessary.

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory, and Mary C. Bateson. Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred. Hampton Press (NJ), 2004. Glossary

- ↑ Bateson, Gregory. 1936. Naven: A Survey of the Problems Suggested by a Composite Picture of the Culture of a New Guinea Tribe Drawn from Three Points of View. Cambridge; Cambridge University Press; Second Edition, with a Revised Epilogue, 1958, Stanford: Stanford University Press

- ↑ Gregory Bateson Naven, 1936, p.181

- ↑ Gregory Bateson Naven, 1936, p.181

- ↑ Communication, The Social Matrix of Psychiatry 245

- ↑ For a thorough account of Bateson's WWII work see: David H. Price: Gregory Bateson and the OSS: World War II and Bateson's Assessment of Applied Anthropology. Human Organization. Vol. 57, No.4, 1998l| There is also extensive discussion about the degree to which anthropology was instrumentalised in David H. Prince Cold War Anthropology, the CIA, the Pentagon and the Growth of Dual Use Anthropology, Duke University Press, 2016

- ↑ (Lipset and others)

- ↑ Angels Fear 12-13

- ↑ Lipset, David. Gregory Bateson: The Legacy of a Scientist. Boston: Beacon Press (MA), 1982.

- ↑ This is in a similar fashion to Lacan's own theory of psychoanalysis, Levi-Strauss' structural anthropology and Jakobson's

- ↑ Calvin S. Hall, A Primer in Freudian Psychology. Meridian (1954)

- ↑ Ruesch, Jurgen, and Gregory Bateson. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2006.248-249

- ↑ Ruesch, Jurgen, and Gregory Bateson. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2006.244)

- ↑ Ruesch, Jurgen, and Gregory Bateson. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2006.

- ↑ Ruesch, Jurgen, and Gregory Bateson. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2006. 239

- ↑ Ruesch, Jurgen, and Gregory Bateson. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2006. 242

- ↑ Ruesch, Jurgen, and Gregory Bateson. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2006.

- ↑ Bateson’s term “economies of entropy” is used in Sacred Unity p.?

- ↑ Ruesch, Jurgen, and Gregory Bateson. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2006.

- ↑ Ruesch, Jurgen, and Gregory Bateson. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2006.

- ↑ Ruesch, Jurgen, and Gregory Bateson. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2006.

- ↑ Bateson drew on Kubie, one of the few proponents of psychoanalysis at the Macy conferences: Kubie, L. S.: Fallacious Use of Quantitative Concepts in Dynamic Psychology." Psychological Quart., 45 Ruesch, Jurgen, and Gregory Bateson. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2006.

- ↑ Ruesch, Jurgen, and Gregory Bateson. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2006.

- ↑ Ruesch, Jurgen, and Gregory Bateson. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2006.