Notes on Method

THE FABULOUS LOOP de LOOP

Cybernetics, in its contemporary sense, came into existence when the traditional notion of feedback loops, which has its origins in engineering (as performed by Ktesibios’ water clock or Watt’s steam engine) was bound to the modern concept of information (that the meaning and context of a message are not connected and that information can be measured in a binary unit).

The two disciplines were later brought together into the term Information Theory and were simultaneously theorised by Norbert Wiener and Claude Shannon.

Cybernetics was practiced and theorised in a number of research cultures, to begin with principally for the U. S. military in the 1930s and 40s, and later in a wide variety of contexts. Post WWII, cybernetic ideas impacted society on all levels, politically, culturally, militarily, scientifically, even as its institutional presence dissipated at the end of the 1960s.

The key principles outlined in Behavior, Purpose and Teleology by Arturo Rosenblueth, Norbert Wiener and Julian Bigelow (1942) and A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts (1943), along with the information theory of Claude Shannon (1947) provided a frame that allowed for the equivalence between mechanical and biological systems.

The first cybernetic creatures (such as those built by Grey Walter and Ross Ashby), self-organised and adapted to their environment, providing models for the workings of the nervous system of animals and humans. If behaviour in both animal and machine is regulated by information flows through a circuit, both might also be understood as ordered through stochastic processes, performing computational acts. This was understood as an expression of negative entropy.

The writers and artists discussed in The Fabulous Loop de Loop sought to accommodate the implications of a "new" epistemology of circular causality to their own fields of research: Lacan to psychoanalysis; Burroughs to literature; the Radical Software group to art and (media) ecology. This epistemological shift did not come over night, I also examine the development of this discourse from the nineteenth century with reading of the work of Samual Butler and, as we approach the era of cybernetics, the work of William Bateson and Kenneth Craik. These figures prepare the ground for a group of thinkers who developed a discourse on cybernetics in the middle of the twentieth century.

The polymath Gregory Bateson wrote in parallel with many of these thinkers. Bateson was a central figure in realizing the Macy Conferences on cybernetics (1946-1953). He was a key figure in reforms to psychiatric practice in the 1950s and was an intellectual force within the ecology and counterculture movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Throughout his career Bateson developed an holistic cybernetic epistemology. Key texts by Bateson, dating from the mid 1930s to the 1970s, will be held as companion stars to the authors listed above. I aim to provide a very slim cross section which describes the institution of a broader cybernetic discourse.

This text is concerned with the way ideas can travel from one discursive space to another. Bateson expresses the protean nature of cybernetic ideas more effectively than any other thinker. Bateson repeatedly draws our attention to an “outmoded epistemology” in which the nineteenth century energy model reaches the point of exhaustion. This, Bateson argues, must be replaced by an “ecology of mind” in which negative entropy is the central agent; in which individual choice provides “the difference that makes a difference”. Bateson's ability to synthesis different bodies of knowledge becomes apparent, as he transits from one epistemological sphere to another without significant violence to reason.

STRUCTURE OF THE TEXT

The Fabulous Loop de Loop comprises nineteen chapters. Each chapter examines attempts (from the 1870s to the 1970s) to narrate a new system of knowledge in which the discourse of energy is replaced by the discourse of information.

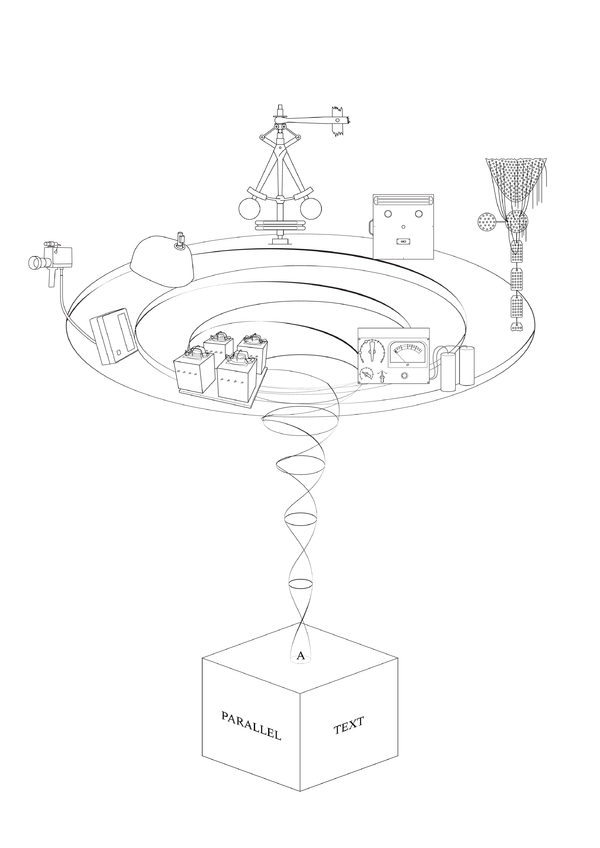

The passage of the cybernetic model of negative entropy will be charted by seven feedback machines. These machines serve as agents in extending the discourse of cybernetics across a number of different scientific, social and cultural domains.

- The Vapour Engine, regulated by the Governor. This self-regulating machine becomes the exemplar of the broad principles of cybernetics and binds the discourse of evolution to the discourse of the machine.

- Gray Walter’s M. Specularix (the Cybernetic Tortoise) was built in the late 1940s. It performed as a model for the cybernetic conception of neural activity;

- Claude Shannon & David Hagelbarger’s SEER (SEquence Extrapolating Robot) was developed at the Bell Labs in the early 1950s. The machine was able to play a human at the game of “ones and twos” and is regarded as one of the first “thinking machines”;

- Alfred Korzybski’s Structural Differential (Anthropometre) (1924) was a “plastic diagram” which, in Korzybski’s theory of General Semantics, modelled the relation between an object-event and the human nervous system. The machine as a technology of self-reflexivity was later adopted, for different purposes, by Gregory Bateson and William Burroughs.

- The E-Meter (Electropsycometer) was used in Scientology auditing sessions. The E-Meter served as a psychological feedback mechanism, regulating the actions and re-actions if the user. For William Burroughs, a Scientologist and media activist, this machine has a strong performative potential which. along with a series of other media apparatus, had the power to reshape reality.

- The Homeostat was developed by Ross Ashby. It explores the degree of self-organization afforded within a complex system. The machine allows for changes to its ultrastable state by adjusting the variables.

- The Sony Videorover II AV-3400 (Portapak). Used within the counterculture of the 1960s the video system became an operational model on which visions of an ecologically sustainable society could be mapped on to a utopian media ecology.

Central to cybernetics was a reassessment of how change and adaptation occur across a wide variety of disciplines such as physics, biology, evolution and ecology. This re-evaluation also reached deep into the social sciences and the humanities, making claims on the discourses of anthropology, psychology, psychoanalysis, aesthetics and sociology.

I use the term “a” cybernetic discourse in the byline to this text, to make clear that The Fabulous Loop de Loop describes the site of an epistemological struggle. The term “cybernetics” is far from stable. In The Fabulous Loop de Loop we will see how different thinkers draw on different elements of the past to establish new foundations and project into different imagined futures.

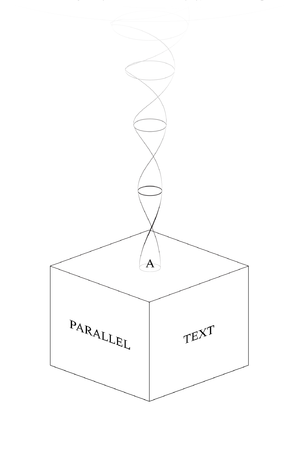

A PARALLEL TEXT

A Parallel Text runs throughout the The Fabulous Loop de Loop. The text helps situate the The Fabulous Loop de Loop within a broader historical and critical context. Parallel Text comprises a series of essays, annotations, extracts and notes which embed the Fabulous Loop de Loop in a broader context. Links to A Parallel Text are provided in the margins of The Fabulous Loop de Loop.

METHODOLOGY

In The Fabulous Loop de Loop I do not introduce contemporary commentary and analysis of this discourse. Although my tools of interpretation in the Fabulous loop de Loop are contemporary (I draw on the theoretical models used by Katherine N. Hayles, Lydia H. Liu, John Johnston and Friedrich A. Kittler, for instance) the Fabulous Loop de Loop does not give explicit reference to them (although they are always appropriately cited). I have put space aside in A Parallel Text for this.

A Parallel Text is one stage of abstraction removed from The Fabulous Loop de Loop. It extends the discourse into the contemporary realm. Here I take the opportunity to reflect on more recent analysis of the shifting terrain of this discourse.

I also take time to consider issues which are outside the range of The Fabulous Loop de Loop itself. These include: cybernetics as an instrument of political reason in the post WWII era and the influence of cybernetics on “post-modern/ post-structuralist” theory.

The Fabulous Loop de Loop examines a discourse of cybernetics as it developed over a century. On reading these various texts, and sticking as closely as possible to the context which produced them, it becomes apparent that all the writers discussed here produce a different epistemological map to describe the territory they inhabit. It becomes apparent that, far from there being a stable narrative of how cybernetics came into being, we see a number of overlapping, entangled and conflicting claims, which in their articulation, produce this discourse.

It is a terrane in which the different protagonists look forward to different horizons and back to different paths of entry. The protagonists in The Fabulous Loop de Loop all adjust to the implications of an epistemological shift. They speak of its past and speculate on its future. They speak from different disciplines as engineers, philosophers, anthropologists, experimental psychologists, psychoanalysts, artists and writers. All of them attempt to accommodate the implications of a new conception of negative entropy, as the model of the regulation and conservation of energy (entropy) shifts to a model of the distribution of information (negative entropy).

To some the news comes as a revelation: Samual Butler recognises the equivalence between mind and matter; Gregory Bateson develops a wholistic cybernetic meta-theory. To others it comes as a shock: Lacan recognises that the Freudian scheme of dynamic psychology needs to be rebuilt from its foundations; William Burroughs understands that literature is revealed as a code that can be scrambled and mixed with other media (that noise can constitute information). All are dealing with the same set of premises and yet all describe a different reality. Here I stress the performativity of this discourse as it feeds information about itself into itself to allow adaptation.