WRITING – CALVINO-SOFTWARE-CYBERNETICS

Time-Binding and Time-Scrambling

“If we find a monkey striking a typewriter apparently at random but in fact [it] is writing meaningful prose we shall look for restraints, either inside the monkey or inside the typewriter” – Gregory Bateson [1]

ANNOTATION–ESSAY

|...| Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967, The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company, pp. 3-27

|...| Gregory Bateson, The Cybernetic Explanation, 1967, StEM, p.460

The early 1960s saw the publication of Eric Havelock’s Preface to Plato, Claude Levi-Strauss’ The Savage Mind, Marshall McLuhan’s The Gutenberg Galaxy and Understanding Media (1964), and Jack Goody and Ian Watt’s The Consequences of Literacy (1963). A new media theory of the 1960s emerged from debate around the dialectic of orality vs. literacy: Orality, which assumed a unity between the speaker, the community, and the language spoken, and literacy, which aids the storage and transmission of the spoken word, using the software of the alphabet. These publications described a trajectory that will take us to Walter Ong’s Orality and Literacy (1982).

In Walter Ong’s reading (building on Millman Perry’s work in the 1920s and Harold Innis’ Empire and Communications, 1950), literacy is a technology which renders the previous medial technology (the mnemonic system of orality) inconceivable and opaque to literate culture. This is because once language enters the field of vision in the form of written symbols (which allow the reader to visualise abstract concepts) it is impossible to un-think it or reverse their mediation. For Ong: “Literacy consumes its own antecedents [it] consumes their memory.” [2] The literates’ relation to language is inextricably associated with its reproducibility in encoded form. Central to this scheme are various forms of software (the alphabet included) which store, mediate and structure memory. Oral cultures survived millennia without need for such a visual-symbolic encoding of natural language and never arrived at the necessity to outsource their memory to external storage systems such as the scroll or codex. [3]

Oral cultures generate patterns, cluster subjects together, cycle rhythmic phrases in Mnmonic loops. These technologies fashion the subjects of orality to an equal degree as their literate counterparts were fashioned by their own technology of memory. For the writers in the early 1960s the software of the alphabet became the means by which to deal with the issue of orality. If the software of the alphabet engendered a crisis in subjectivity, over the centuries the human subject managed to naturalise the code, sublating it and making it equivalent to natural language, engendering an illusion that writing was in some way a direct translation of nature.

The technology of the alphabet, once called out as such, becomes a self reflexive medium, it is exterior to the subject that speaks, it is passed through the circuit of writing and the embodied writer. I discuss in The Fabulous Loop de Loop that after cybernetics, art recognised its own self-reflexivity, and that self-reflexivity became a condition of the production of art itself (see chapter, The Fabulous Loop de Loop), just as the Radical Software group understood the intersubjective relation engendered by the media they use (the Protapak). At the same time William Burroughs understood the necessity of facing the consequences of technologies of inscription which are radically exterior to the subject. Other writers in the 1960s started to understand their own practice in specifically cybernetic terms – including the OuliPo Group (L'Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle.

Italo Calvino's Cybernetics and Ghosts (1967) stands at the crossroads between cybernetics as a proposed new epistemology and cybernetics as a mode of literary and self-reflexive production. The text simultaneously explains the ways in which knowledge is being reordered in response to recent developments in cybernetic and information theories, and examines the implications of that move. Calvino recognizes that through the adoption of combinational and computational technologies of writing we have reached a limit, but the ambition of the writer must be to operate at the borders and extend the limits of language – to produce that which cannot be predicted, that which has never been previously combined, and which cannot be computed.

Calvino's text gives an account of the history of western literature encompassing the most advanced contemporaneous writers, tel quail and olioupo. The argument Calvino offers will be familiar, positing a given language as a stochastic system ordered by probability, ordered by restraints, a system in which making a choice (on the level of the letter or the word) brings order (anti-entropic).

Calvino begins in the era of orality, with the figure of the storyteller, in relation to the folk imagination. The teller of folk tales is one who works under the conditions of restraint, limited by the vocabulary and structure of his language, ('“verbs, subjects and predicates”); and given the limited constellation of characters, grouped into neat, structured, binaries by Calvino., (“father and son, husband and wife, brother in law and uncle”);and given the few actions that could be performed within a story (“born, die, copulate, sleep, fish, hunt....”). [4](36) This is an echo of Claude Levi-Strauss’ Elementary Structures of Kinship. Levi-Strauss, speaking of the structure of the tales he had studied in Brazil, would describe them as “a system of logical operations between permutable terms, so that they could be studied according to the mathematical processes of combinational analysis.”[5] “The storyteller explored the possibilities implied in his own language by combining and changing the permutations of the figures and the actions, and of the objects on which these actions could be brought to bear. What emerged were stories.”[6] Calvino notes that such "structural analysis" has become a self-reflexive method or means of production of texts in the 1960s, citing the Tel Quel group, [7] However exponents of “scriptualism”, Calvino goes on, maintain that “a certain number of logico-linguistic (or better yet syntactical-rhetorical ) operations remain reducible to formulas (that) are more general as they become less complex”[8](40) This combinationality creates a change in the nature of the text and a change in the function of the writer, and consequently for Calvino the self-reflexive writer must be both post-humanist and anti-hermeneutic. (This reflects Lacan’s dialectical observation that the discourse of knowledge is sublated by the discourse of the machine).

Calvino establishes the cybernetic explanation that restraints are the conditions for the production of text. He then goes on to explain that, given text is produced under the condition of certain restraints, feeding a self-awareness of this structure into the work itself produces a different order of reading and writing. Calvino then outlines the framework of a world which seems to be increasingly discreet, as opposed to continuous. Thought which “until the other day” appeared to be “fluid, evoking linear images such as a flowing river...” Or images such as gaseous clouds, which were associated with spirit, we now tend to “think of as a series of discontinues states”.

Calvino then picks up cybernetics as the central agent in his text, with particular reference to how the 1st generation of post war cyberneticains conceived of early cybernetic creatures they built as models for the brain underlining the notion that the 'soul' has been replaced by “rapid passage of signals (...) with which our skulls are crammed”.[9] Calvino extrapolates the cybernetic convention that just as the moves on a chess board are innumerable, so the human mind (a chessboard representing hundreds of billions of chess pieces ) would not be possible to make “all possible plays”. Calvino offers an elegant unpacking of the relation between restraint and indeterminacy which is at the heart of the cybernetic explanation and, by extension, uncovers the cybernetic paradox that will later permeate his works, most prominently in Cosmicomics, “every division into parts, tends to (...) make things more complicated.”[10] Calvino likens this to the paradoxes of Zeno which refused the continuity of space, creating an infinite number of points (Achilles). Except that the cybernetic abacus only has two numerals from which it generates infinite complexity.

Calvino develops a discourse between Hegel and Darwin, who were wed to a notion of historical and biological continuity, which “healed all the fractures of dialectical antithesis [Hegel] and genetic mutations [Darwin]”[11]In the current era this has been washed away by the tide of historical mathesis; just as in the realm of biology the discovery of DNA follows the logic of the divided binary transmitting information to future generations; [12]the dialectic of historical and biological continuity now fall under the order of finite qualities which run to complexity. Literature must come to terms with the expulsion of the spirit of history and the annulment of the uniqueness of man in the chain of being. Calvino's next move is a fascinating one because he remarks on how similar structural linguistics and information theory were to each other and yet were “raised on quite different terrain”, he remarks on how the linguists are also talking of codes and messages, how entropy is discussed on the level of literature. This misreading naturalises the commonality rather than recognise that structural linguistics is structurally, historically, and institutionally linked to cybernetics. It is telling that less than fifteen years after cybernetics' dramatic entry into European intellectual life, the link between structuralism and cybernetics is not recognised, it seems Calvino was unaware the degree to which his own argument has its origins in the United States.

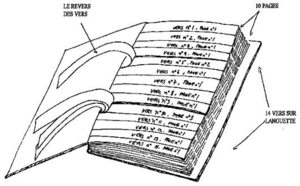

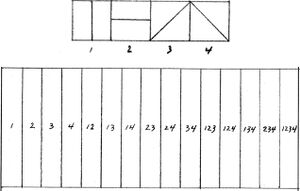

In Cybernetic Explanation (1967)[13] Gregory Bateson had noted that, “If we find a monkey striking a typewriter apparently at random but in fact [it] is writing meaningful prose we shall look for restraints, either inside the monkey or inside the typewriter” The cybernetic explanation is always negative and is dependent on restraints. Nevertheless, restraints can combine to create “a unique determination” [14]. The literary exponents of this cybernetic explanation were the OuliPo Group (Ouvroir de las Litterature Potentieelle), which was founded in 1960 as a sub commission of the College de ‘Pataphysique Potentielle.[15] The most pristine example of this new philosophy of literature was Raymond Queneau’s A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems (1961). Cent mille milliards de poèmes was a combinational poem comprising 10 pages each containing 14 verses (10 to the power of 14 = 100,000,000,000,000, one hundred million million, possible permutations).

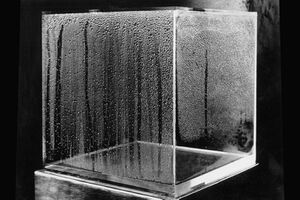

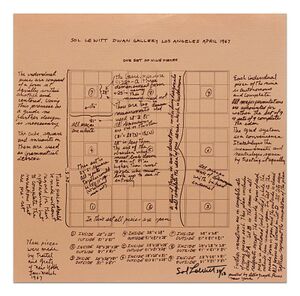

The cybernetic explanation, the necessity of restraints, also serves as a foundational principle of conceptual art, from Sol LeWitt’s procedural instructions for the making of a work, to the minimalism and post-minimalism of Dan Graham (a keen reader of Bateson's work and contributor to Radical Software) Hans Haake’s masterpiece Condensation Cube 1965 (an ecological-cybernetic model).

I draw out these practices because although they are accounted for by the cybernetic explanation they do not, as practices, feed through computers, or use programming code to be realised. This is also true of the zoo of electronic animals produced in the early years of cybernetic (the cybernetic tortoise, the homeostat, the moth-bedbug) scuttling across what Andrew Pickering describes as the “performative theatre”.[16]The cybernetic explanation does not necessitate computers but does rely on the notion that “the subject matter of cybernetics is not events and objects but information carried by events and objects”.[17] […] When Bateson discusses the differentiation between the map and the territory, “a differentiation badly programmed computers and communicating organisms fail to maintain”[18]

Just as ritual systems conflate wine and blood, bread and body, induction and deduction, arising from scientific discourse, are difficult to keep apart. In The Cybernetic Explanation context and content cannot be separated (signified and signifier are also problemitised) Bateson: “the word is the context of the phoneme but the word only has meaning in a larger context “without context their would be no communication.”[19] The use of a particular letter excludes 25 other possible letters (constraint).[20]

Calvino then comes to the Oulipo, which arise from the College de Pataphsique, described as a college of “intellectual scorn”. An explanation of Queneau's Cent mille millards de poemes, establishes that it is already a machine for making literature (a few years after Calvino's lecture the Oulipo exhibited their literary works mediated by machines in the 1970 exhibition Information). It was reasonable for Calvino to imagine a machine that would go beyond being an “assembly line” for texts and could realise “all the most jealously guarded attributes of our psychological life.”[21] These are, after all, only “linguistic fields”. And given that existing classical texts are very routine and ordered, according to the structures of grammar and syntax codified by linguistic analysis, it would follow that the writing machine would be a machine of disorder, which would produce texts capable of “turning its own codes upside-down”.[22]

The job of the avant-garde writer would be best suited for a machine which has no illusions of its own uniqueness, is not haunted by the classical spirit, which understands text for what it is.

The text is a catalogue of procedures which carries the signature of the author – which is quite easily simulated, and represents only a slight diversion from the precepts of a given structure. We are left in a position where the text is only ever a technical construct for which the author is redundant. As we approach the point of absurd reduction, Calvino now turns the tables: “A thing cannot be known when the words and concepts have (never been used) in that order” […] “The struggle for literature is in fact the struggle to escape the confines of language; it stretches, out from the utmost limits of what can be said; what stirs literature is the call and attraction of what is not in the dictionary.”[23]

Here Calvino seems to begin the argument again, as if feeding the same material through the literary machine to produce a different result. He returns to the storyteller and to Levi-Strauss, and the relation of the story to the rite (a series of signs with many meanings).[24] Here the rite might be understood as the space of the material practice of discourse. Within this space, in which the narrator narrates the pre-programmed litany, there is a space of prohibition and taboo, a “language vacuum that draws words up into its vortex” literature can speak from such a vortex, it can speak the unspeakable. Calvino will later argue that this has been the dialectical function of literature throughout “mans” development.

“Myth acts on fable as a repetitive force” obliging it to go back on its tracks... “The unconscious is the repository for these repressed, prohibited utterances.” Calvino's account holds some striking similarities to Lacan’s re-evaluation of Freud a decade earlier:[25]

“The unconscious is the ocean of the unsayable, of what has been expelled from the land of language, removed as a result of ancient prohibitions. The unconscious speaks-in dreams, in verbal slips, in sudden associations-with borrowed words, stolen symbols, linguistic contraband, until literature redeems these territories and annexes them to the language of the waking world.” [26] When applied to the Lacanian cybernetic “linguistic contraband”, “borrowed words” might be interpreted as how, for the cybernetic Lacan, the imaginary must draw on the symbolic to process the real. The symbolic is exterior, shared amongst us. The imaginary is required to formulate and process the unsayable. Language in Lacan, Calvino, and cybernetics is a machine that speaks us.

Calvino places this obligation of literature to say the unsayable into a broader dialectical context. The paradox of the enlightenment is that “the more enlightened our houses the more their walls ooze ghosts”.[27]

The development of literature, through saying the unsayable, has witnessed the successive exorcism of ghosts: Shakespeare exorcised the ghosts of the medieval world; Sade and Goethe introduce the novel; Poe liberates the ghosts of Puritan America and popularizes literature; Lautreamont “explores the syntax of the imagination”, laying the basis for the moment when the unconscious meets the machine with the surrealists who discover “an objective rationale totally opposed to that of our intellectual logic” the surrealists propose a challenge to rationalism and by extension, they propose a radical exteriority.[28]To exorcise our ghosts is to divest us of all metaphysical support structures, literature then becomes an apparatus for expunging the spirit, an apparatus that describes literature's limits (in all cases these developments constitute a challenge to the structure of text).

Calvino now focuses on the relation between combinational play and the unconscious in artistic activity, concentrating on Freud's interest in puns. The pun is a combinational entity, (its utterance relies on the possibility of it being something else, the right word in the wrong placeholder). The pun presents itself to our consciousness and releases something previously at worst repressed or at best held at arms length. Calvino is now ready to reach a conclusion:

“Literature is a combinatorial game that pursues the possibilities implicit in its own material, independent of the personality of the poet, but it is a game that at a certain point is invested with an unexpected meaning, a meaning that is not patent on the linguistic plane on which we were working but has slipped in from another level, activating something that on that second level is of great concern to the author or his society.”[29]

For Calvino the mythic function comes if one persists in “playing around with narrative functions”. For him fables proceed myths; ingrained patterns of myth are repeatedly challenged by new combinations emerging from the unconscious (the forbidden). We witness long periods when structures remain unchallenged and periods when the prohibited is written. And later the stakes shift: “the spirit in which one reads is decisive: it is up to the reader to see to it that literature exerts its critical force, and this can occur independently of the author's intentions”.[30] The reader becomes the situated critic of text. Here Calvino speaks to an aesthetics and ethics of self-reflexivity. At this time, Calvino, Bateson, and Lacan all examine the relation between myth and rite in the oral tradition, and storytelling in the literary tradition. It is at this time that we see Cybernetics as analysis and performance (this is developed by Burroughs in his performative use of text). In contemporary contexts this is well established, in Kenneth Goldsmith’s Uncreative Writing(2011), for instance, which accepts Calvino’s point that a writer is, in a sense, a word processor, conforming to the restraints provided by the technology of writing. Although Calvino's diagnosis is similar to Goldsmith’s they offer a very different prognosis. If in the current era machines perform post modern literature, it does not mean that writers are simply writing machines. For Calvino the perameters of writing offer a challenge to be overcome.

Calvino is on a crossroads at the limits of humanism. Calvino argues for the development of literature in line with the development of “Man” but here man is reborn into the ethics and aesthetics of a cybernetic self-reflexivity. This is a similar end-point to Bateson and the media-ecologists Radical Software, who construct the writer as post-human writing-machine and the reader-performer who seeks a limit beyond the text they are a producing. This is the limit at which what has already been said moves aside for that which has never been expressed. A moment at which the circuit of reality is extended.

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, The Cybernetic Explanation 1967, StEM

- ↑ Walter Ong, Orality and Literacy p.15

- ↑ Walter Ong, Orality and Literacy p.15

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company (1986) pp.2

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company (1986) p.4

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company (1986) p.2

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company (1986) p.5

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company (1986) p.5

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company (1986) p.6

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company (1986) p.7

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company (1986) p.8

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company (1986) p.8

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, StEM, p. 405

- ↑ Gregory Bateson, StEM, p. 405

- ↑ Andrew Hugill. 'Pataphysics, A Useless Guide, MIT, 2012 p. 58

- ↑ Andrew Pickering, The Cybernetic Brain

- ↑ Gregory Bateson The Cybernetic Explanation, StEM, 407

- ↑ Gregory Bateson The Cybernetic Explanation, StEM, 408

- ↑ Gregory Bateson The Cybernetic Explanation, StEM, 408

- ↑ Gregory Bateson The Cybernetic Explanation, StEM, 408

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company (1986) p.10

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company (1986) p.11

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company pp.16

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company pp.17

- ↑ Lacan ,Seminar II, 1954-55

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company p.17

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company p.17

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company p.18

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company p.20

- ↑ Italo Calvino, Cybernetics and Ghosts, 1967 The Uses of Literature. San Diego, New York, London. Harcourt Brace & Company p.24