JAKOBSON–LEVI-STRAUSS–CYBERNETICS

ANNOTATION:

|…| Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Levi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011, PP. 96-126

Abstract to this annotation: the principle actors in establishing structural linguistics and structural anthropology – Roman Jakobson and Levi Strauss – were enthusiastic advocates of American cybernetic and communications theory. Crossing between Europe and the United States they extended the discourse within European intellectual life through institutions such as Ecole Libre des Hautes Etudes, in New York, and UNESCO.

Although Lacan’s interpretation of cybernetics, in contrast to Jakobson and Levi-Strauss, broke with Saussurian linguistics, Cybernetic theory and games theory enabled Lacan to develop a contemporary theory of the unconscious (see CYBERNETIC TORTOISE and SEER).

Roman Jakobson

François Dosse has traced the beginnings of the connection between post-war structuralism (linguistics and anthropology) back to 1942 when Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roman Jakobson met at the New School for Social Research in New York, were jointly recipients of funds from the Rockefeller Foundation, which strongly supported cybernetics, communication and media studies with a view to fostering scientific solutions to social problems.[1] In the 1930s and into the 1940s Warren Weaver, co-author with Claude Shannon of The Mathematical Theory of Communications, was the director of the natural sciences division of the foundation. During the 1940s the foundations served, as ‘an interdisciplinary scientific apparatus’ [cite] that supported European scientists and theorists who had been displaced by the war. One notable recipient was Theodor Adorno - who would undoubtedly have understood cybernetics as an instrumentalisation of reason. Indeed, Adorno was to have personal experience of how his own form of research would fall out of favour as the support for media orientated, critical research project funding was withdrawn and handed to projects such as Jakobson’s and Levi-Strauss’. In the 1950s the Rockefeller Foundation preferred to fund the more ‘scientifically’ credible endeavours, which were characteristically ahistorical and functionalist. This included a 50,000 dollar grant to Jakobson’s project, under the auspices of the category “Language, Logic, and Symbolism.” The annual communiqué’s stated aim was to “facilitate the application to living languages of the mathematical theory of communication worked out by Mr. Claude E. Shannon and Mr. Warren Weaver.” [2](Awarded by a department Warren Weaver headed.)

As the temperature of the cold war lowered to Artic degrees the foundation moved toward the creation of a “world-wide fraternity of scientists” which would draw into the fold exiled scientists and intellectuals who had made a contribution to the interdisciplinary revolution.

In 1948 Jakobson had been given a grant to travel to Europe to compile a survey of worldwide linguistics, although Jakobson understood the trip as a mission to inform European intellectuals of the interdisciplinary revolution that was taking place in the US. At the end of 1948, ahead of a meeting to discuss a follow-up trip, Weaver mailed a copy of The Mathematical Theory of Communication by Shannon & Weaver. Jakobson’s response was profound (and echoed the ideals of the Macy conferences):

“I fully agree with W. Weaver, ‘one is now, perhaps for the first time, ready for a real theory of meaning,’ and of communication in general. The elaboration of this theory asks for an efficacious cooperation of linguists with representatives of several other fields such as mathematics, logic, communication engineering, acoustics, physiology, psychology and the social sciences. Of course when this great collective work will be fulfilled it will mean a new epoch indeed.” [3]

From 1950 onwards Jakobson was engaged in a frenzy of associations and alliances between institutions and individuals on both sides of the Atlantic, in an attempt to further bolster the nascent science of structural linguistics with the theories of communication and cybernetics. He served as editor of the interdisciplinary journal Information and Control, held a seat on the steering committee of MIT’s Center for Communications Sciences, was co-editor of a planned book series promoting the cross-fertilization of the social sciences and engineering, and he was visiting professor at MIT. Whilst in Europe, he continued to promote the work of cyberneticians to Levi Strauss[4]

The Rockefeller Foundation

From the 1940s the Rockefeller Foundation had funded a francophone community of intellectuals, the central figures of which were Hungarian semiotician Thomas Sebeok, Charles Hockett, Claude Levi-Strauss, and Roman Jakobson. All researched at the Ecole Libre des Hautes Etudes, which was a ‘university-in exile’ in The United States financed by the Rockefeller Foundation [5]

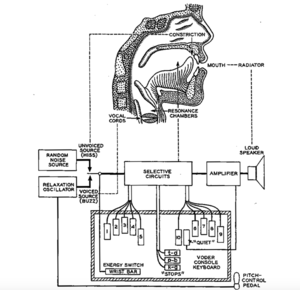

Here the ideas that Jakobson had worked on at the Prague Linguistic Circle from the 1920s & 1930s were further developed. These were based on de Saussure’s conception of language constituting a system of difference. This relation would provide the armature for a cybernetically based conception of structural linguistics as the 1940s turned towards the 50s. Shannon’s communications theory and Wiener’s conception of feedback were to legitimize the field of structural linguistics as a bone fide science. Jakobson’s fascination with the new apparatus of communication which provided models for our understanding of language is illustrated by his trip with his Linguistic Circle to the A&T auditorium in New York to see a demonstration of the Voder. The machine demonstrated the operations of human speech by breaking it down to a series of sounds that could be reassembled when played on a phonetic keyboard [6]. This was similar to the Vocoder – voice-encoder-decoder (developed in 1938). The apparatus engineered an understanding of human speech and grammar as computational and reconfigurable. Vocoders (and its kissing cousin Auto-tune) are now ubiquitous presences on many popular recordings, but they began life as a means to compress the human voice through a narrow channel; an early application of the Vocoder to send scrambled and mutated messages to combatants in Europe during WWII. It was used during the war as a way of encrypting messages – Shannon worked at Bell Labs on an encryption system which allowed Churchill to have phone conversations with Roosevelt (Project X). It is here where Shannon met for lunch-time conversations with Alan Turing who was also working on voice encryption-decryption. [7] The technicians from Bell Labs provided students at the Ecole Libre with a demonstration of the Voder.

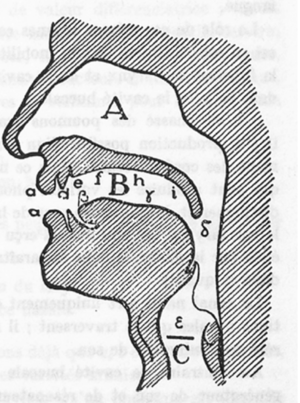

The team from the Bell Labs would later visit the Ecole Libre to show the researchers how speech could be electronically mapped as frequencies. Such interdisciplinary collaborations aided a discourse that understood human speech as analogous to non-human communications devices – (which served to sink human consciousness deeper into the black box as we continue to deal exclusively with input and output). The phonic apparatus of the human body and its functions were given diagrammatical representations in the literature produced for the Voder exhibition.

In these the visual vocabulary of circuitry was combined with anatomical diagrams of the human voice organs (mouth, tongue, throat, &c). Images like this were familiar to readers of Ferdinand Saussure’s Course on General Linguistics. The combination created a cyborg complex of machine and human.

Bridging the mechanical and the human is a structure surprisingly similar to Claude Shannon’s famous message-receiver / signal- noise communications diagram.

Devices such as the Voder and the Vocorer seemed to reinforce the particular/ity of the components of language, which Saussure’s ideas stressed, but it also invited an understanding of these theories of language as approaching their reward as an exact science (for instance, not effected by the contingencies of history or politics) and pertaining to a greater theory of communication within which the voice and language are sublated.

Historian of science, Lily Kay has noted one of the abiding commonalities between the structuralists and the cyberneticists was that they were interested primarily in relations, in signifiers rather than referents or in objects in themselves,[8] which leads to a valorisation of information above all else. Spurred on by Shannon-Wiener communications theory Jakobson theorized language as a coding system that structured information exchange. The Saussurean terms la langue (language-system) and la parole (speech or speech act) are translated into “code” and “message” respectively. Jakobson: “the concepts of code and message introduced by the communications theory are much clearer, much less ambiguous, and much more operational than anything the traditional language theory has to offer’ (1963: 32).”[9]. Jakobson would later contend that: “the problems of output and input in linguistics and economics are exactly the same.” Leading Geoghegan to argue that Jakobson’s extension of Saussurean linguistics into the realm of communication theory […] “provided mechanisms for strategically conjoining linguistics, electronics, and economics.” [10]

Claude Levi-Strauss

The material links between the development of structural anthropology and cybernetic theory are just as strong.

Throughout Warren Weaver’s directorship of the natural science department of the Rockefeller Foundation he strove to further the aims and objectives of communications theory and cybernetics (he was also at the NRMC).

In 1949, just as he had done with Jakobson, Weaver sent Levi-Strauss a copy of his and Claude Shannon's The Mathematical Theory of Information.[11] Thereafter Levi-Strauss enthusiastically applied his influence wherever possible to further the unification of his own field to that of communication and cybernetic theory. Insisting that theories of communication could be applied to all forms of human activity and could be understood as constituted by feedback circuits. In the field of anthropology, for instance, ‘‘elementary structures of kinship’’ were controlled by elements such as phonemes, goods and the exchange of wives that could be circulated and that this circulation structures circuits which could be analysed scientifically with the aid of computational devices.[12] As a well-connected practitioner in his field he used every possible opportunity to refract his own practice through the lens of American cybernetic, information, and communication theory, and to give this complex increased political leverage. Levi Strauss (following a stint at the French Embassy)[13] was the director of UNESCO’s International Council of Social Sciences – and even attempted to include passages of Wiener’s Cybernetics in the UNESCO constitution. [14] He was also an officiator in the related Office on the Social Implications of Technological Change, which afforded him the opportunity to lecture and publish in a mode of address in which politically volatile global issues (class, gender, poverty, technological advancement, &c) were framed as technological issues which operated under the order of the feedback circuit and could be administered computationally. [15]. Levi-Strauss put forward plans to establish – with the assistance of UNESCO and Rockefeller Foundation funding – a scientific institute which would bring the natural and human sciences together and allow his own, Jackobson’s and other colleagues’ hypotheses to be tested empirically. [16]

- ↑ Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Levi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011, p. 104

- ↑ Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Le´vi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011, p. 104, p 36

- ↑ Cited in Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Levi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011, p.110

- ↑ Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Levi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011, p.113

- ↑ Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Levi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011, p.104

- ↑ Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Levi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011.p.104

- ↑ Turing bio 250

- ↑ In Lafontaine Céline. The Cybernetic Matrix of ‘French Theory’; Theory, Culture & Society, SAGE, Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, and Singapore, Vol. 24(5):2007 p. 33

- ↑ Lafontaine Céline. The Cybernetic Matrix of ‘French Theory’; Theory, Culture & Society, SAGE, Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, and Singapore, Vol. 24(5):2007 p. 33

- ↑ In Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Levi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011

- ↑ The Mathematical Theory of Information (1948) by Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver| Weaver was responsible for making some of the more technical aspects of Shannon's theory accessible to the layman.

- ↑ Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Levi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011.p.104 p.117

- ↑ Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Levi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011.p.104 p.109

- ↑ Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Levi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011.p.104 p.109 and 117

- ↑ Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Levi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011.p.118

- ↑ Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Levi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus, Critical Inquiry 38, 2011.p.104 p.118