Introduction: The Foundations of a Cybernetic Discourse

“I think that cybernetics is the biggest bite out of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge that mankind has taken in the last 2000 years. But most of such bites out of the apple have proved to be rather indigestible—usually for cybernetic reasons. Cybernetics has integrity within itself, to help us to not be seduced by it into more lunacy, but we cannot trust it to keep us from sin.” — Gregory Bateson, From Versailles to Cybernetics (1966)

The twenty-one chapters chapters of The Fabulous Loop de Loop (Floop) examine attempts, from the 1860s to the 1970s, to narrate a new system of knowledge in which the discourse of energy is replaced by the discourse of information.

In 1858 the naturalist Alfred Wallis, in correspondence with Charles Darwin, noted that the way evolution is regulated in the natural world, through adaptation to changes in the environment, was akin to the self-regulation exhibited through the governor on a steam engine. [1]The governor is the “safety valve” within the machine that makes sure the engine does not “blow its top”. The governor ensures that information about the machine’s performance passes through the system which allows the machine to adapt to changes within that system. This process is negative feedback in essence, and it embodies a principle which today organises many aspects of our life, from the thermostat in our heating system to the behavioural checks and balances built into our Fitbit.

The novelist and speculative thinker Samuel Butler (who also corresponded with Charles Darwin) built on Wallis’ observation. In 1863, Butler published “Darwin Among the Machines”, in which he speculated that through the same principles of self-regulation expressed in the steam engine, machines could evolve capabilities beyond those of their human creators. [2]Butler was one of the first to draw an equivalence between adaptation of the machine and adaptation of an organism or ecology – this machine-organism equivalence would become central to cybernetic reasoning in the following century.

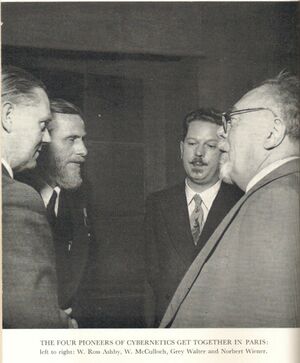

In the middle of the twentieth century Gregory Bateson, the anthropologist and co-organiser of the Macy conferences on cybernetics (1948-1953), noted that Wallis and Gibson’s observations marked the beginnings of an epistemological shift. For Bateson, from the moment when the steam engine was introduced, feedback, or negative entropy, had become the agent which explains change in the world. [3]In this period, Bateson stresses, the emphasis shifted toward how information passes through a system to allow stability and adaptability (homeostasis), as opposed to the nineteenth century model of the distribution of energy within a system (dynamic equilibrium). The distinction between these two conditions will be discussed throughout this text, but for now, I draw your attention to how Bateson, in his comparison between Wallis and Butler, drew on different elements of the past to establish new foundations for knowledge. He then projected this foundation into an imagined future in which we recognise the performative power of negative entropy. Bateson, like others in the cybernetic circle discussed in this text, recognised in cybernetics an opportunity to ring the epistemological changes and become, in essence a discourse theorist of a new era. In Floop I will chart how different thinkers across the span of a century, in disparate cultural fields, draw on a discourse of cybernetics to establish new foundations for knowledge. From the Cyberneticians like Norbert Wiener and Warren McCulloch – to the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, the writer William Burroughs and media activist group Radical Software ¬– all drew on the cybernetic notion of negative entropy to inform their practice and their world view.

Here is the top and tail of the fabulous loop de loop: it begins with an observation about the similarity between the operation of feedback machines and the operation of evolution and this loops around to a wholistic meta-theory about the nature of the world.

In studying the work of these individuals, I ask myself “what kind of world are these thinkers describing?”, and, by extension, “what kind of reality are they proposing?” and to take it to its performative extreme: “what kind of reality are they producing?” I am not concerned whether they are right or wrong but rather in what kind of world they wanted their discourse to produce. I recognise that in making Floop I will inevitably make my own claims, either implicitly or explicitly, (it is a cybernetic truism that the subjectivity of the experimenter will feed back into the experiment). I have given the bi-line “a” cybernetic discourse to avoid the epistemological grandstanding which characterised the propositions of some of the protagonists in this text, [4] My motivation was to better understand the affordance of “negative entropy” (feedback) in its materiality and in its specificity and to understand that even grand overarching meta-theories have their beginnings in specific actions – from the brain science experiments of the 1930s, to the video therapy sessions of the early 1970s – and through specific material relations. Where, for example, war-time servo-machines meet advanced brain research; or when a group of young video-makers recognise the significance of the “media ecology” they have created.

SEVEN MACHINES

Central agents in the performative feedback loop described in Floop are the machines the cyberneticians designed and wrote about. I stress that these machines were more than diagrams which describe a principle or matter of fact. “in their metal", [5]these machines make claims on the world. Feedback machines, like organisms and ecological systems, carry news of order back through the system. (Gray Walter’s cybernetic tortoise, for instance, behaved like an organism struggling to follow the light; Ross Ashby’s homeostat self-corrected like an ecological system). In this text I examine seven such feedback machines and discuss how they served as performative agents to a cybernetic discourse as it developed from the nineteenth century into the second half of the twentieth century. This sets the ground for understanding a discourse of cybernetics as a material practice to which human and machine both make claim.

The seven machines are:

- The Vapour Engine (steam engine), regulated by the Governor. This self-regulating machine becomes the exemplar of the broad principles of cybernetics and binds the discourse of evolution to the discourse of the machine.

- William Gray Walter’s M. Specularix (the Cybernetic Tortoise) was built in the late 1940s. It performed as a model for the cybernetic conception of neural activity;

- Claude Shannon & David Hagelbarger’s SEER (Sequenced Extrapolating Robot) was developed at the Bell Labs in the early 1950s. The machine was able to play a human at the game of “ones and twos” and is regarded as one of the first “thinking machines”;

- Alfred Korzybski’s Structural Differential (Anthropometre) (1924) was a “plastic diagram” which, in Korzybski’s theory of General Semantics, modelled the relation between an object-event and the human nervous system. The machine can be understood as a technology of self-reflexivity.

- The E-Meter (Electropsycometer) was used in Scientology auditing sessions. The E-Meter served as a psychological feedback mechanism, regulating the actions and re-actions of the user. For William Burroughs, a Scientologist and media activist, this machine has a strong performative potential which, along with a series of other media apparatus, had the power to reshape reality.

- The Homeostat was developed by William Ross Ashby. It explored the degree of self-organization afforded within a complex system. The machine adapted to disturbances to its ultrastable state.

- The Sony Videorover II AV-3400 (Portapak). Used within the counterculture of the 1960s the video system became an operational model on which visions of an ecologically sustainable society could be mapped onto a utopian media ecology.

NEGATIVE ENTROPY-FEEDBACK-CYBERNETICS

The cybernetic discourse outlined in Floop is based on three principles which I will go into greater detail a little later in this introduction

- a machine-organism equivalence (the factors which self-organise an organic system are equivalent to the factors that order a cybernetic system)

- a new definition of purpose (purpose is relational, as opposed to goal directed)

- a materialist conception of mind (fundamental to the cybernetic vision examined in this text is an understanding that consciousness (or “mind”) emerges from a series of material conditions which adapt to change through a series of feedback loops through a system.

From a cybernetic perspective, these three principles are necessitated by a new understanding of the affordance of feedback. Before outlining these three elements I will outline the role of negative entropy within this text in general terms.

Cybernetics, the “science of feedback” was practiced and theorised in several research cultures, to begin with principally for the U. S. military from the 1940s, and later in a wide variety of contexts. After World War II, cybernetic ideas impacted society on all levels, politically, culturally, militarily, scientifically, even as its institutional presence dissipated at the end of the 1960s.

Cybernetics, in its contemporary sense, came into existence when the traditional notion of feedback loops, which has its origins in engineering (as performed by Ktesibios’ water clock or Watt’s steam engine) was bound to the modern concept of information – that the “signal” within a message represents the measure of order and the “noise” was a measure of disorder.

The word "Kubernetes" is ancient Greek, and the source of the word “steersman”. The “father of cybernetics”, Norbert Wiener, resuscitated the term in the mid-twentieth century to describe how iterative feedback could guide ordered action. [6] The third century Neoplatonist, Plotinus had invoked the term in a negative sense. In Plotinus’ interpretation, the steersman should not be so preoccupied with worldly events, should they be distracted from higher thoughts from which these events originate. [7] The emphasis of this text – and that of the cyberneticians of the second half of the twentieth century – is precisely opposite: it is through engagement with the material specifics of the world that one can develop a clearer understanding of it. [8]

Cybernetics, as theorised by Norbert Wiener et al., seemed to resolve the curious issue that however much things tend to get in a muddle, however much things fail and decay, they also (in the natural world and in human society) tend toward organisation and order.

In Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and Machine (1948), Wiener provided a precise relation for entropy and information, in the sense that units of information (Binary units or bits) within a message can be measured against noise (which is the measure of entropy in the message), with characteristic drama he wrote: “Organism is opposed to chaos, to disintegration, to death, as message is to noise.”[9]

It is possible, stated Wiener, in his popular book The Human Use of Human Beings (1950) “to interpret the information carried by a message as essentially the negative of its entropy, and the negative logarithm of its probability. That is, the more probable the message, the less information it gives. Clichés, for example are less illuminating than great poems.”[10]

If entropy framed the understanding of the central scientific and social issues of the nineteenth century – powering its steam engines, spinning its mills – organising its discourse of economies of energy; negentropy recognises the relationship between information and energy that frames the current age of communication – the discourse of ecologies of information.

Wiener’s theory of negentropy provides a solution to a conundrum which had plagued evolutionary theory throughout the nineteenth century: how in an entropic universe could order be established and maintained and how can it increase in complexity? Wiener’s equation for negentropy accommodated biological order within a general field of physical flux because it provided the context for self-organisation and adaptation. [11]

WIENER’S-CYBERNETIC-EPISTEMOLOGY

In Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Gregory Bateson translates Wiener’s idea as follows:

“The technical term ‘information’ may be succinctly defined as any difference which makes a difference in some later event. This definition is fundamental for all analysis of cybernetic systems and organization. The definition links such analysis to the rest of science, where the causes of events are commonly not differences but forces, impacts, and the like. The link is classically exemplified by the heat engine, where available energy (i.e., negative entropy) is a function of a difference between two temperatures. In this classical instance, “information” and “negative entropy” overlap.”[12]

Bateson builds his argument of “the difference that makes a difference” to argue the relation between negative entropy and conscious purpose within human beings.

Bateson: “Wiener points out that the whole range of entropy phenomena is inevitably related to the fact of our knowing or not knowing what state the system is in. If nobody knows how the cards lie in the pack, it is to all intents and purposes a shuffled pack. Indeed, this ignorance is all that can be achieved by shuffling.”

Negentropy here enters the realm of culture, as human beings interfere with the randomising machinations of the entropic universe. Humans systematically set out to “trick” the second law of thermodynamics – organising against the relentless forces of improbability. Bateson next argues that because choice is bound to order, in seeking information humans also seek values. Bateson describes a man who “for his breakfast,[...] achieves an arrangement of bacon and eggs, side by side, upon a plate; and in achieving this improbability he is aided by other men who will sort out the appropriate pigs in some distant market and interfere with the natural juxtaposition of hens and eggs.”[13]

Here Bateson extends the individual choice to a larger ecology of choices: man + environment. The prosaic example of a man choosing his breakfast makes the key relation between negative entropy and Bateson’s ecology of mind which will underlie the Fabulous Loop de Loop. For Gregory Bateson human decision-making serves as “Maxwell’s demon”, bringing order to an entropic system.

MACHINE-ORGANISM EQUIVALENCE

My emphasis in Floop will be that the key thinkers of the new epistemology of cybernetics – Wiener, McCulloch and Bateson among them – were avid narrators of the development of their emerging science in a lineage of anti-cartesian, non-thomian thinking which was already well established in the centuries before. In this sense, I read them as discourse theorists who argued the stake of past and present knowledge.

In that vein I emphasise that the discourse of experimental psychology (neurophysiology), which had developed since the beginning of the twentieth-century, was central to the discourse of cybernetics as it developed in the 1940s. Many of the cyberneticians were leading brain researchers before and after the war. In the case of Kenneth Craik, Ross Ashby and Grey Walter, the cybernetic “thinking machines” they created arose directly from their brain research. [14] The new technologies of scanning devices and predictive servomechanisms, which had researched for the war effort, when added to the repertoire of brain experimentation developed in the 1920s and 30s, produced new models of behaviour and new perspectives on the relationship between machine and the organism.

The British cyberneticians Ross Ashby, Kenneth Craik and Grey Walter, and the American cyberneticians Lawrence Kubie and Warren McCulloch were well established in the discourse of experimental psychology, which developed clear arguments of how mind is constituted – from an “anti-cartesian”, “non-thomian” perspective (which is to say, they refused an essentialisation of “self”). The new affordance of servo-machines within this established discourse allowed for the extension of experimental psychology into first-order cybernetics. The meeting of experimental psychology and war-time weapons research produced a new formal theory of feedback and control technologies which begged fundamental questions about the nature of organism and its relation to environment, and about the nature of mind.

At the heart of the cybernetic discourse of the 1940s and 1950s is the idea of machine-organism equivalence, which had also been at the heart of neurophysiological research in the preceding decades. This is the notion that a machine – to the extent that it modelled an organism, in that it could order its environment – could “think”, “learn”, and “adapt”. Simultaneous with the development of these “thinking machines” was a reassessment of what constituted “thinking” itself.

REDEFINING "PURPOSE" AND "THINKING"

In their seminal paper Behavior, Purpose and Teleology (1942),[15] Arturo Rosenblueth, Norbert Wiener and Julian Bigelow sought to provide a new definition of purpose – best demonstrated by the hypothetical cybernetic devices I describe in the Fabulous Loop de Loop. These devices, which did not ‘resemble human beings’ would nevertheless exhibit complex behaviour despite being fed little information. The simplest and clearest demonstration of this claim was realised a few years after the publication of Behavior, Purpose and Teleology, in Gray Walter's Tortoise (1948), one of the first in a menagerie of teleological mechanisms.

In Behavior, Purpose and Teleology, the behaviourist approach is distinguished from the teleological approach (later to be termed cybernetics). Behaviourism has some relation to the teleological approach but only to a limited extent. Behaviourism ignores the relation between the object and its surroundings (context), which is of central importance to the cyberneticians. The approaches also differ in that teleology is goal-directed[16], Wiener et al make the distinction between purposeful machines and non-purposeful machines, “Purposeful active behaviour may be subdivided into two classes: “feed-back” (or “teleological”) and “non-feed-back” (or “non-teleological”).[17] All feedback machines require negative feedback to operate, meaning “some signals from the goal are necessary at some time to direct the behaviour” [18] We can compare the conditions of a functioning thermostat (feedback machine) with a kitchen clock (non-feedback machine). The latter may allow exterior output (to be wound up) but outside signals do not circuit through it to modify its behaviour, as is the case with a thermostat. The clock is incapable of learning and of adapting (and in this sense it is entropic, it will always need energy from the outside to wind it up). For ‘teleological mechanisms’[19], cause-and-effect relations are replaced by ‘circular causality’ which requires negative feedback as a regulator (Wiener will later identify negative feedback as negentropy). The senses of the organism (touch, sight, and proprioception) guide a given action through constant feedback and adjustment. ‘Circular causality’ can occur in man and machine or machine and machine, but all are goal-directed and regulated within a circuit.[20] Many goal-directed circular-causal activities can be understood mathematically, if not through the tractable (linear) mathematics in which A causes B. Behavour is therefore understood as systemic and probabilistic.

After the publication of Wiener’s Cybernetics in 1948, the relation between information and energy became more clearly defined – order is re-enforced as information loops through the system. In this context behaviour, thinking, and mind are imminent to system – mind cannot be divorced from the material circuitry in which it is produced. This has significant implications to our conception of behaviour and requires a radical reconsideration of the concept of mind. For the cybernetic group at the Macy meetings the new conception of teleology extended the realm of exact science, revising the epistemology of modern science[21], which traditionally was the study of the intrinsic way in which beings and things functioned.[22] The teleological approach shifted the emphasis toward the interrelation of things and objects.

REDEFINING “MIND”–THINKING (MACHINES)

The idea that mind is constituted through a series of iterative, non-conscious actions is central to a cybernetic understanding of human consciousness. The cybernetics of the mid-twentieth century also makes an abiding link between stochastic systems (systems of probability) and biological systems such as the human brain. This position is re-enforced by a seminal paper which helped define the debate on machines and organism in the post war era.

In Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity (1943), McCulloch and Warren Pitts had put forward the notion that neural activity was produced within a network of circuits, cycles, and loops which are ordered by the laws of probability. They suggested that single neurones (which in binary action, fire or do not fire) conduct logical operations and act as logic gates which organise information within a nerve net in the brain. In this way, the brain organises a superabundance of information that at any given time showers through the nervous system. Thus the neural net selects and feeds back information which is conducive to adaptation and self-correction. Neurons fire on a chain and are linked in the same way logical propositions are linked, they argued. One could, therefore, view a nerve net as operating like a machine or computer.[23] The McCulloch-Pitts Model provided a theoretical frame that allowed for the equivalence between mechanical and biological systems (specifically in relation to the brain)[24] allowing both to be understood as encoding and decoding systems. Which is to say, biological organisms (including the brain) and servo-mechanisms constitute local negentropic systems.

The first, simple, cybernetic creatures – Claude Shannon’s Rat, Norbert Wiener’s Moth-Bedbug, Ross Ashby’s Homeostat, Grey Walter’s Tortoise[25] – displayed all the properties explained in Behaviour, Purpose and Teleology and accorded to the McCulloch-Pitts Model: they were self-organising, self-directing, adapting and orientated with their environment. Although their behaviour was complex – and went beyond the repertoire of stimulus and response modelled in behaviourism – it could nevertheless be located within a matrix of probability. Behaviour in both animal and machine is regulated by information flows through a circuit and both might be understood as performing computational actions (stochastic- probabilistic-statistical). As Norbert Wiener explained: “It is […] therefore, best to avoid all question-begging epithets such as ‘life’, ‘soul’, ‘vitalism’, and the like, and say merely in connection with machines that there is no reason why they may not resemble human beings in representing pockets of decreasing entropy in a framework in which the large entropy tends to increase.” [26]

GREGORY BATESON -IN CONVERSATION

The polymath Gregory Bateson will be a reoccurring figure in Floop because he made claims for a cybernetic epistemology which went further than anyone else discussed in this text. Bateson’s epistemological commentary abides through the entire circuit of the Fabulous Loop de Loop, from before the post-war “cybernetic moment” [27] through to the post-counterculture media tacticians of the early 1970s [28]. Through his engagement with anthropology, psychiatry, psychoanalysis, ecology and aesthetics Bateson sought to articulate a cybernetic, wholistic meta-theory which had negative entropy as its central organising agent. Bateson repeatedly draws our attention to an “outmoded epistemology” in which the nineteenth century energy model reaches the point of exhaustion. This, Bateson argues, must be replaced by an “ecology of mind” in which negative entropy is the central agent; in which individual choice provides “the difference that makes a difference”.

Bateson was born in 1904, into a world where the entropic universe was passing into a new universe of information and communication. The development of his cybernetic epistemology leaves clear traces of this transition, as Bateson draws on visionary figures who intuited the new order – Samuel Butler, Clark Maxwell, and his father the geneticist William Bateson to name a few– and reframes their work in the light of the cybernetic explanation provided by Craik, Ross Ashby, Grey Walter, McCulloch, and Wiener. Bateson was influential on a group of ecologists, psychologists and media theorists who would usher in a new “media ecology” at the end of the 1960s. As much as these writers were concerned with how the world works and how the human mind and the brain function, they also acknowledged the pressing need to reframe the nineteenth-century thermodynamic discourse from the new perspectives provided by cybernetics. Throughout Floop, I will place Bateson in conversation with these people, whether as the interlocular with Lacan, as the psychoanalyst comes to terms with Freud’s dynamic psychology in the age of cybernetics; or with the theorist of General Semantics, Alfred Korzybski with whom Bateson negotiates the sense of Korzybski’s term “the map is not the territory” in a post-cybernetic era ; or with William Burroughs with whom I establish a three way conversation between Bateson, Korzybski and Burroughs on the impact cybernetic notions of negative entropy have on literature; or with the Radical Software group, who channel Bateson’s “ecology of mind” into the realm of a new “media ecology”. Although I will follow a (generally) chronological trajectory – as the seven machines provide a material anchor for our loop and situate the discourse in a particular time – by necessity, my references to Bateson will be elastic, as Bateson throughout his career gathered the work of many minds, across many years and many disciplines, safely into his wholistic cybernetic meta-theory (“ecology of mind”).

I do not seek to reproduce Bateson’s position, and I am not interested whether Bateson’s claims are true or false –nor am I interested in whether the claims of any of the thinkers I discuss are true or false – but I am interested in how a discourse is produced, how it is sustained and how, in its many facets and interrelations, it can produce reality. In this examination of the material practices of discourse I resist allowing for the “bootstrapping” of reality (which is, incidentally, a cybernetic notion) [29] but rather emphasise the emergence of discourse through material production. I don’t believe one can “hallucinate” reality, in the manner of an AI data set. I have learned, while writing Floop, that ideas, however abstract and bizarre they may seem, have their origins in the world of things. Coding a program, splicing a tape, cutting, and pasting a text, building a machine with the materials and knowledge at hand, making a “plastic diagram”, all contribute to the construction of a discourse and produce the ground on which “abstract” notions become possible. Floop represents an attempt to make this process visible.

BIBLIOGRAPHY–FABULOUS LOOP DE LOOP

- ↑ Alfred Russell Wallis: On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely From the Original Type (S43: 1858) http://people.wku.edu/charles.smith/wallace/S043.htm

- ↑ S. Butler: Darwin Among the Machines (1863); Evolution Old and New, Or the Theories of Buffon, Dr. Erasmus Darwin and Lamarck, as Compared With That of Charles Darwin (1879)

- ↑ Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind (STEM), 260

- ↑ Gregory Bateson’s: “ecology of mind”; William Burroughs’ claim that “language is a virus from outer space”)

- ↑ Wiener's preferred term

- ↑ Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and Machine. (1948)

- ↑ Erik Davis, TechGnosis, Myth, Magic & Mysticism in the Age of Information, North Atlantic Books , 2015, p 89.

- ↑ I recognise that I have introduced an elephant into the room. I make only passing mention of Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver’s Information Theory, which was theorised in parallel with Wiener’s theory of negentropy in the 1940s. In 1948 Shannon and Weaver’s Information Theory divorced information from its carrier, postulating for the first time that the means of delivery differs from the semantic content of the message. My emphasis in Floop will be on the embodied, performative affordance of cybernetic apparatus, the people who made them and the people who discussed them, as opposed to an Information Theory which emphasises the disassociation between the message and its carrier. Early versions of this text placed Shannon and Wiener shoulder to shoulder, alongside (near-) contemporary thinkers who theorised this relation (including Johnston, Hayles, Winthrop-Young & Wurtz, Liu, Kittler, Regis Debray, Baudrillard and others).

- ↑ Wiener in Harries-Jones EU&GB 108

- ↑ Wiener HUoHB De Capo 1954 edition

- ↑ Harries-Jones EU&GB p. 108

- ↑ Bateson StEM

- ↑ Bateson StEM

- ↑ Pickering, Andrew. Cybernetics and the Mangle: Ashby, Beer and Pask. Social Studies of Science Volume: 32 Issue 3, 2002: pp. 413-437

- ↑ Arturo Rosenblueth, Norbert Wiener and Julian Bigelow, Behavior, Purpose and Teleology, Philosophy of Science 10 (January 1943)

- ↑ Heims the Cybernetic Group, 15

- ↑ Arturo Rosenblueth, Norbert Wiener and Julian Bigelow, Behavior, Purpose and Teleology, Philosophy of Science 10 (January 1943) p.19

- ↑ Arturo Rosenblueth, Norbert Wiener and Julian Bigelow, Behavior, Purpose and Teleology, Philosophy of Science 10 (January 1943) p.19

- ↑ Arturo Rosenblueth, Norbert Wiener and Julian Bigelow, Behavior, Purpose and Teleology, Philosophy of Science 10 p. 15

- ↑ S. Heims the Cybernetic Group, 16

- ↑ S Heims CG 16 and 32

- ↑ S.S. Heims the Cybernetic Group P?

- ↑ Heims CG

- ↑ N. K. Hayles, New Media Reader, 145-148

- ↑ A. Pickering The Cybernetic Brain

- ↑ Wiener, in Lafontaine, Matrix of French Theory, 32

- ↑ Kline, R. R. The Cybernetics Moment: Or Why We Call Our Age the Information Age. Baltimore, MD: JHU Press, 2015

- ↑ For an instance of this see: Gregory Bateson, Awake, Radical Software No 5 Volume 1, p.33; and Frank Gillette, Video:Process and Meta Process, Syracuse NY: Everson Museum of Art, 1973.

- ↑ For Bateson’s influence on computer pioneer Douglas Engelbart see, Bardini, Thierry. Bootstrapping: Douglas Engelbart, Coevolution, and the Origins of Personal Computing. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2000