LEIBNIZ – CODE–ISOTYPE–BASIC

Time-Binding and Time-Scrambling

ANNOTATION:

|...| Steve Rushton, Otto Neurath Web-Dossier, Stroom Den Haag, 2006-2007[1]

|...| Lydia Liu The Freudian Robot, 2011

|...| Gauti Sigthorsson, Leibniz Sends an Email, The International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Society, Volume 1, Number 5, Common Ground, 2005/2006

A series of literary, administrative and scientific experiments in the early twentieth century (preceding the cybernetic era by two decades) served to establish a stochastic discourse of written language. These included Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, Jung’s word association system, Breton’s Exquisite Corpse and C. K. Ogden’s BASIC.

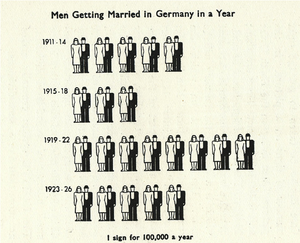

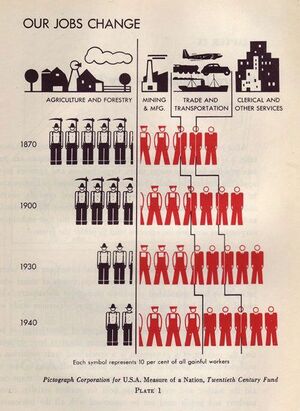

Charles Kay Ogden’s BASIC (British, American, Standard, International, Commercial) English (1930)[2] streamlined the English language to 850 words and was designed to serve as a language of trade and diplomacy in the increasingly globalised 20th century. In the 1930s and 1940s BASIC had a great deal of currency: Churchill recognised the opportunity for basic to provide the discursive foundation for the British Empire as Britain’s global supremacy was ceded to the United States. The system might be understood as a companion to Otto Neurath’s ISOTYPE (internatonal System of Typographical Education), the first fully coherent system of information graphics. Nuerath’s book about ISOTYPE, International Picture Language, The First Rules of Isotype [3] was written in BASIC. Neurath, who attempted both the unification of science – with his Encyclopaedia and the Picture Dictionary– and, through his invention of Isotype, attempted to make complex information intelligible to the masses in the form of the combination of succinct images and select words.

Ogdan's BASIC was satirised in George Orwell's 1984, with the neologistic language ‘newspeak’. In H. G. Wells' Shape of Things to Come (1933) BASIC serves to unite humanity in a utopian future. Ogdan was the first English translator of Wittgenstein and co-author, with I. A. Richards, of an early work on semiotics, The Meaning of Meaning (1923).

Claude Shannon acknowledged the fundamental importance of BASIC and in an essay that approached Ogden’s system in the light of his own information theory. BASIC was discussed by Norbert Wiener and John Von Neumann at the Macy Conferences on cybernetics. Could BASIC be used as the basis for a future "computer language"? [4]

Michel Serres has argued that we have “begun anew to dream of the Mathesis Universalis”, [5] which is to say we have taken Leibniz’s promise of a universe understandable through calculus at its word and accepted the universality of the code as the only legitimator of knowledge. Leibniz also posited the Atlas Universalis, an attempt to chart knowledge pictorially. Both the Mathesis and the Atlas had an influence on communications theorists in the 20th century.

Initiatives like Isotype and BASIC English (proceeding cybernetics by some twenty years) sought to reduce complexity through a series of basic units of information which could be universally understood. As well as standing as a recognition of modernist communication theory’s debt to the Mathesis Universalis, they also stand as instances whereby problems of communication are understood to be software problems – both Isotype and BASIC English can easily be understood as applications which direct the flow of knowledge (what can and cannot be said) in particular ways. It is evident that simplification to aid ‘user friendliness’ had been a central issue to communication at least from the time of Leibniz.* The critical issue of what it is possible to say within the modalities of a given language (the limitations of software in its broadest sense), along with the day to day use of software, and the degree to which the internet is sometimes understood as the fulfilment of the dream of the exposition of the sum of all knowledge, will also have to be temporarily suspended. I mention them here as indicators that once we stop thinking about communication primarily on the basis of its linguisticallity a whole area of potential research objects open up to us. [6]

The desire to create the exposition of all knowledge predates Leibniz, of course – Rerum Divinorum et Humanorum Antiquitates, St. Isidorus (560-636) Etimologies, Alsted Encyclopaedia Omnia Scientiarum (1630), and Diderot & D'Alembert Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers (1751-1765) –but it was Leibniz who proposed a system of knowledge predicated on calculus, which is a direct antecedent of electronic computation. On the broader point, it is evident that the word ‘software’ requires a definition that spans centuries rather than decades. [7]

- ↑ Link to Rushton's Like Sailors on the Open Sea, Dot Dot Dot Issue 14, 2006, Eds. Dexter Sinisterhttps://www.stroom.nl/media/DotDotDot14.pdf,

- ↑ Charles Kay Ogden, Basic English: A General Introduction with Rules and Grammar, 1930

- ↑ Neurath, Otto, International Picture Language, The First Rules of Isotype, University of Reading, 1980 (1936)

- ↑ Lydia Liu The Freudian Robot + Cybernetics: The Macy Conferences

- ↑ Serres, M., cited in, Sigthorsson, Gauti, “Leibniz Sends an Email”, The International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Society, Volume 1, Number 5, Common Ground, 2005/2006, p.1

- ↑ Steve Rushton Neurath Web-Dossier, Stroom den Haag, 2006-2007

- ↑ See Leibniz and the Encyclopaedia Project, Olga Pombo.)